Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

One morning in my early adolescence, my father woke me up for school, and I told him a terrifying dream I’d had about a bear. I focussed on the overwhelming sensory dimensions of the dream, the way the bear had appeared colossal yet lifelike. “It was really hairy,” I kept repeating, “and it smelled bad.” My father, a psychologist, listened carefully and then gently suggested that the dream might reflect anxiety about my changing pubescent body. “Especially,” he added, “in its bare form.” He lingered on the homonym until I grasped his meaning, my face turning red. “I’m not sure it was actually a bear,” I said quickly. “It was maybe more like a lion.” My father raised his eyebrows and smiled before leaving my room.

Growing up in Manhattan in the nineteen-seventies and eighties, I was used to having my dreams interpreted by my parents, who were both Freudian psychoanalysts. They had each been through lengthy analyses themselves (my mother for five years, my father for more than twenty), and they encouraged my three siblings and me to relay our anxieties through Freudian methods, sometimes pulling out a set of Rorschach cards if they thought one of us seemed particularly troubled. They saw patients in our Upper West Side apartment, a portion of which was dedicated to their consultation space. In addition to his clinical work, my father was a researcher; his primary mission was to prove, empirically, the existence of the Freudian unconscious.

I often wonder whether some of his dedication arose from an identification with Freud himself. Like Freud, my father was a Jewish intellectual of Eastern European background who was deeply committed to science and intent on expanding its reach. And, like Freud, he possessed tremendous self-conviction, perhaps in compensation for the fact that others viewed him as something of an eccentric. In my father’s case, this partly had to do with his physical presence: at six feet four, with a full head of curly brown hair and a hearty laugh, he might have been an imposing figure, were it not for a slight stoop, a distracted mien, and a dress style so negligent that it often included stained shirts and mismatched shoes. Then there was the reality that my father’s ideas were always just south of normal. Preoccupied not only with unconscious fantasy but with its potential for harm, he interpreted everything through a Freudian lens. He could spend hours analyzing his own psyche or engaging in self-hypnosis, and was convinced that, if he shared what he knew with people, he could help them to lead happier, more productive lives. He would often write to famous athletes and politicians, using his psychodynamic knowledge to explain their failures and offer advice on how to better their game.

The idea that we are hiding from ourselves—harboring thoughts and desires that we are not aware we possess—is perhaps Freud’s greatest contribution to modern thought. Philosophers before him, from Descartes to Kant, had long celebrated the mind as a source of internal coherence. But Freud imagined a mind at war with itself. Freudian theory tells us that the feelings we experience most strongly in our conscious life (love for our children, admiration of our friends, satisfaction in our accomplishments) can be informed, on an unconscious level, by their opposites (resentment, competition, ambivalence). Emerging through a phenomenon that Freud called “the return of the repressed,” these latter emotions haunt us, often resulting in neurotic symptoms that we don’t understand. With the help of a trained analyst, we can search for insight, but progress is often elusive and difficult to measure.

That’s where my father’s work came in. He believed that he could tap into the unconscious in the laboratory, allowing for a degree of scientific precision unavailable in a clinical setting, where the interpretations of a therapist can’t be gauged for accuracy. His experiments involved the Freudian developmental phases—the oral stage, the anal stage, the Oedipal complex, et cetera—because these are often understood as the starting points for neurosis. (According to Freud, failure to move through these psychosexual stages results in a “fixation” that can shape adult personality.) By my father’s logic, scientifically proving that self-sabotage was tied to unresolved Oedipal hostility, for example, could help therapists more effectively treat this problem. In hindsight, penis envy hardly seems like the kind of thing one can verify in a controlled trial. But my father had a deep faith that everything—even a phenomenon as nebulous as unconscious desire—could be subject to data-driven investigation.

Although he himself was beloved and respected by his colleagues, his approach was not universally admired. Classic Freudian psychoanalysis had its heyday in America in the fifties and early sixties, but by the seventies a shift was under way. Psychiatrists who had previously embraced psychodynamic training were increasingly drawn to the fields of genetics and neurochemistry, and academic psychologists, who had always been skeptical, began further distancing themselves from Freudian theory. By the last quarter of the twentieth century, psychoanalysis had largely branched off from the medical and academic establishments, even as it became a cultural touchstone, invoked relentlessly in Woody Allen films and on coffee mugs marketed as “Freudian sips.” In 1975, the medical biologist Peter Medawar pronounced psychoanalysis “the most stupendous intellectual confidence trick of the twentieth century,” and in 1980 the term “neurosis” was eliminated from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). In the face of this opposition, my father felt that his work was more important than ever.

In his free time, he soft-tested his theories on our family. When my older sister, an accomplished athlete, began to choke during tennis matches, my father attributed her losses to Oedipal anxiety, believing that her failure to triumph over weaker players resulted from displaced guilt about aggressive urges she was feeling toward him or my mother. So he did what any concerned father might do: he devised an audio recording that he secretly played in her room while she slept. Its looping message—“Beating Mom is O.K., beating Dad is O.K.”—was designed to sanction unconscious competitive feelings. If her Oedipal guilt were countered, my father reasoned, my sister would realize her full athletic potential.

Did it work? Who knows. My father claimed that it did, but my mother was never so sure and remained wary of his interventions. She understood it as her job to keep his professional enthusiasms in check, especially when it came to experimenting on their children. As for my sister, she never even knew about the audio recording until we discovered it years later among a trove of cassette tapes of a similar nature. I suppose that the episode sounds monstrously intrusive now, but, to this day, it’s difficult for me to understand it this way. As bizarre as my father’s home experiments seem, they still resonate as acts of care.

In his laboratory trials, my father attempted to access people’s unconscious through a procedure he developed called Subliminal Psychodynamic Activation (S.P.A.). In S.P.A., human subjects are exposed to written words and pictures for four milliseconds at a time—too quick for the conscious mind to pick up but long enough to allow for unconscious recognition, according to early research in the field of subliminal perception. To flash these texts and images, my father used a tachistoscope—an enormous rectangular device with a viewfinder and knobs for controlling how long the image would be displayed. One of the earliest uses of the tachistoscope occurred during the Second World War, when fighter pilots were shown pictures of different aircraft models for fractions of a second to promote faster recognition of enemy planes.

At the beginning, my father chose messages that were designed to activate already existing psychopathologies, such as phobias, thought disorders, and compulsive behaviors, which, according to Freudian doctrine, are the consequence of guilt and anxiety brought on by unconscious aggressive or libidinal fantasy. Stir up the fantasy by flashing a related message, the thinking went, and you were bound to set off defensive processes and exacerbate the symptoms. For my father, these experiments could prove that psychological distress was tied to specific unconscious wishes, and although aggravating symptoms was not ideal, the effects were mild and short-lived (less than fifteen minutes, according to one of his experiments).

In some of his early studies, my father focussed on stuttering, which Freudians believed to be linked to the anal phase of development. This is the period when children gain increasing mastery over their bowels, withholding their excrement or expelling it everywhere, much to the frustration of their parents. The child’s pleasure in doing this, Freud thought, is linked to an aggressive impulse that should, in the course of normal development, resolve itself. In a letter to the Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi, in November, 1915, Freud wrote that “stutterers . . . have projected shitting onto speaking.” From that idea was born a theory (developed principally by the Austrian psychoanalyst Otto Fenichel) that stuttering represented an anally regressive desire to assert one’s will by retaining and expelling speech.

In a 1976 paper co-authored with two other psychologists, my father describes how he gathered a group of twenty-two people who stuttered and asked them to perform a series of verbal tasks, such as telling a story in response to a picture. Next, he used the tachistoscope to expose them subliminally to different stimuli: a neutral message (PEOPLE THINKING, accompanied by an image of two people facing each other with bland-looking expressions), an “anality stimulus” (GO SHIT, accompanied by a crouched figure defecating), and an “incest stimulus” (FUCK MOMMY, accompanied by a nude couple in a sexually suggestive pose). The people who stuttered, he found, showed increased speech pathology in relation to the GO SHIT message but not in relation to the other two, appearing to tie stuttering to the issue of anal conflict rather than to other psychosexual stages like Oedipal fantasy.

Related experiments likewise yielded results that seemed to corroborate classic psychoanalytic theory. A group of thirty people with schizophrenia, for example, demonstrated increased thought disorder following subliminal exposure to the aggression stimulus (DESTROY MOTHER) but not in response to the incest stimulus (FUCK MOMMY), seeming to demonstrate that schizophrenia is tied to conflict over unconscious hostile, rather than libidinal, wishes. In short, my father’s work appeared to show that subliminal perception was a real and verifiable phenomenon, as were the Freudian principles on which diagnosed psychopathology rested.

Of course, much of this seems mind-boggling in retrospect. Along with the obvious questions these experiments now raise—Why was DESTROY MOTHER considered more aggressive than FUCK MOMMY? Don’t these messages register equal doses of hostile misogyny?—there’s the more serious issue of attributing disorders like stuttering and schizophrenia to psychodynamic rather than biochemical, neurologic, and genetic causes. And did these strange conclusions justify exacerbating symptoms in patients, even if the effects were mild and transient?

Of course, as a kid I didn’t think about any of this. I was nine years old when my father published his 1976 paper, and, to the extent that I paid attention at all, I was mostly intrigued by the tachistoscope. We had one in our apartment. Affectionately referred to in our family as “the tac,” it was about half the size of a twin bed and sat on a large table in my father’s office, surrounded by all those crazy cards. Most shocking to my childish sensibility was the one that read GO SHIT. (I have no memory of a FUCK MOMMY card. Perhaps my father was more discreet with that one.) I would beg to look at the cards through the tac until my father agreed to set up the machine. Then I would adjust the speed of transmission so as to find the exact moment when I could no longer read the inscriptions and they blurred into a flash of light.

In my memory, the blur is connected to the blurred image of my father—flickering and just out of reach. He was always working, even after dinner and on weekends, always a bit oblivious to everything going on outside his experiments. Plagued by insomnia, he usually entered his home office around 4 A.M. and stayed there until it was time to head off for work at the Veterans Administration or N.Y.U., where he had laboratories. Once, I passed by his office late on a Sunday morning and found him sitting, as always, in his brown houndstooth reclining chair. He was still wearing his pajamas, the buttons of the shirt askew, and his eyes were bloodshot with lack of sleep. Stacks of papers encircled him, and the smell of peanuts, which he constantly snacked on, lingered in the air. I understood that he was doing what my mother called “important work,” but why, I wondered, was it so messy? I organized his books, brought empty plates to the kitchen, even rebuttoned his shirt. Later, I overheard my mother refer to my actions as arising from “vestigial Oedipal desire,” but, more than a love object, I think that I yearned to be a caretaker to my father, whose failure to look after himself made him vulnerable in my eyes.

Sometimes on weekends he would take a break, and we would play hangman or Boggle or ask each other riddles. He had a Freudian preoccupation with wordplay, and I loved a pun almost as much as he did (my dream about the bear notwithstanding). But, after a few rounds, he would appear fatigued and invariably propose what he called a “sleeping contest”—competitions in which we would “race” to see who could fall asleep faster. He always won, and after two or three minutes I would return to my room, wondering at his strange notions of fun. I had friends whose fathers worked all the time and were largely absent. My father was around a lot and appeared genuinely interested in me, but spending time with him always seemed to involve exiting the tangible world.

At some point in his research, my father hit on a new message for the tac. This one was designed to ameliorate rather than exacerbate psychopathologies. He began by using it on people with schizophrenia, and it worked so well that pretty soon he was testing it out on typical populations, who, according to his data, were likewise transformed by its effects. The golden message responsible for all this health and felicity? MOMMY AND I ARE ONE. It was a phrase intended to gratify unconscious infantile wishes since, according to classic psychoanalytic theory, all infants yearn for symbiotic connection with their primary caretaker. In the fifties, the Hungarian psychiatrist Margaret Mahler theorized that the infant’s security in this symbiotic bond ultimately allowed it to mature and individuate successfully. Later theorists, building on Mahler’s insights, postulated that occasionally encouraging adult patients to recapture this symbiosis in their fantasies could help them overcome anxiety and negotiate feelings of isolation. In the words of the psychoanalyst Gilbert Rose, “To merge in order to reemerge may be part of the fundamental process of psychological growth.” With MOMMY AND I ARE ONE, my father hoped to aid patients in this process and mitigate their most debilitating neuroses.

My father knew a thing or two about neurosis. To begin with, he was a first-order hypochondriac. His own father and four of his uncles had died of heart disease, the youngest at age thirty-nine. Attempting to stave off a similar fate, my father took his pulse multiple times a day and recorded it, along with other data about respiratory patterns and chest tightness. These observations filled reams of datebooks that he consulted frequently—to what end it was never totally clear. In his free time, he combed Prevention magazine, searching for the latest longevity craze: Bran! Selenium! Powdered milk! For years, he consumed fistfuls of garlic pills daily, which he believed promoted healthy arteries. At some point, he added nightly glasses of green cabbage juice to the regimen. My siblings and I complained that our whole apartment smelled like rotting salad, but my father was undeterred.

Many of my father’s recreational activities betrayed a desire for merged experience. He began jogging in Central Park in the sixties—before the practice was popular—because, he claimed, it made him feel at one with the universe. He found it relaxing to tune our analog television set to Channel 12 and stare at the static. He disappeared into his office for long periods to practice Transcendental Meditation. As a young girl, I found these behaviors baffling, but, seen through the prism of his work, they seem like attempts to achieve what Freud, invoking the French dramatist Romain Rolland, called “oceanic feeling”—a sensation “of something limitless, unbounded.” My father, like Freud, was not a religious man, so MOMMY AND I ARE ONE may have been the closest thing to spiritual transcendence that he could imagine.

In any case, the phrase quickly became a mantra in our house—the answer to every ailment, the punch line to every joke. For a holiday present for my father one year, I created a pillow with MOMMY AND I ARE ONE stitched across it. (My plan was for him to keep it on his analytic couch, but that idea was quickly nixed since, as my father reminded me, the phrase must be presented subliminally to work.) Another year, my sister fashioned a mock tachistoscope out of a huge refrigerator box, complete with message cards, redesigned to reflect an alienated teen-age sensibility, which read something like MOMMY AND I ARE COMPLETELY AND TOTALLY SEPARATE, GO SHIT AND THEN FIND ME SOME NORMAL PARENTS.

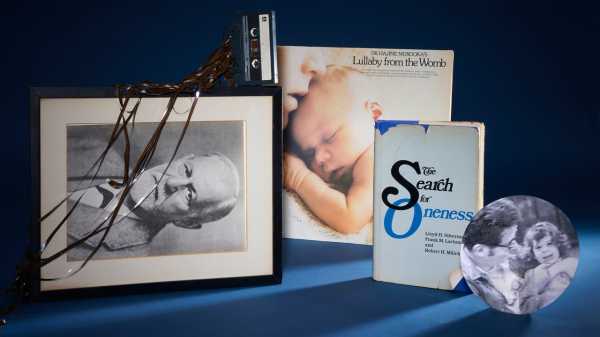

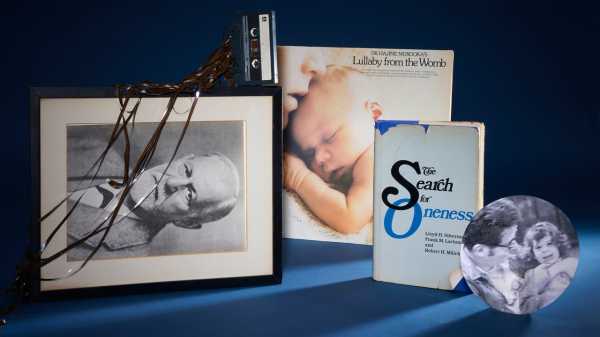

Even when the phrase was not explicitly in use in our home, its logic hung in the air. During my early adolescence, I went through an extended period of insomnia that my father sought to cure through an album titled “Lullaby from the Womb,” which he played for me nightly. Released in 1974 by the Japanese obstetrician Hajime Murooka, the record consisted of the pulsating sound of blood rushing through the aorta and umbilical cord of a pregnant woman. Murooka created the album for babies born prematurely, surmising that their occasional distress was due to “homesickness” for the mother’s womb. The album’s cover featured a naked infant sleeping on its mother’s breast. I don’t remember whether it cured my insomnia—I only remember my mortification when a friend came over and picked it up.

“What’s this?” she asked, holding the album cover at a distance from her between two fingers, like a soiled diaper.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s supposed to help me sleep. My dad’s idea.”

“Of course it is,” my friend responded sympathetically. My father’s weirdness was legendary.

Yet out in the professional world his symbiosis experiments proved extremely successful. Women with insect phobias showed fewer symptoms after being subliminally exposed to MOMMY AND I ARE ONE. Smokers craved cigarettes less. In one study conducted by a graduate student in my father’s lab, college students subliminally exposed to the message performed better on their final exams, with marks averaging almost eight points higher than those who got the neutral message PEOPLE ARE WALKING.

In high school, I went through a phase of being anxious about my schoolwork, and my father tried to soothe me by humming. This, too, emerged from his obsession with mother-infant relations. In the early sixties, the Russian linguist Roman Jakobson had observed that some of babies’ first sounds are open-mouthed vocalizations (“ahhh”) but that soon afterward they tend to gravitate to the phoneme “mmmm”—the one sound they can produce when their lips are latched to the nipple and their mouths are full. Jakobson theorized that out of this the word “mama” was born, a word that is almost identical in every language of the world. My father believed that the “mmmm” sound could calm people by unconsciously reminding them of the satisfying experience of being breast-fed, and he began to periodically incorporate “mmmm” into our conversations about homework or an upcoming exam. It was subtle—a prolonged contemplative noise he would make in response to one of my anxious rants—but by high school I was attuned to his interventions and increasingly resistant, especially when he began to encourage me to hum, too.

Nonetheless, something about these talks must have stuck, because in eleventh grade I entered the Westinghouse Science competition with a research project called “Effects of the Sound ‘Mm . . .’ and the Heartbeat on Emotional Response and Creativity in Adolescents.” It earned me a semifinalist award and a ceremony hosted by the New York City mayor’s office, where, standing among hard-core physics and engineering students, I tried to explain the humming experiment to baffled Ed Koch aides. Without realizing it, I had become a convert.

My father’s experiments were met at the time with a mixture of excitement and leeriness. A long profile in Psychology Today in 1982 characterized his work as pathbreaking but also conveyed incredulity. “His data are so surprising that many psychologists simply cannot believe in them,” the reporter, Virginia Adams, wrote. His critics were numerous and far-ranging. They pointed out that the notion of a single message that could work on everyone’s unconscious was preposterous. They also doubted the efficacy of his subliminal-activation method. “It is asking a great deal of the human organism to expect subjects not only to take in a five-word sentence but to interpret it in a very particular way,” the psychologist Donald Spence said. The data, critics contended, reflected unintentional bias or were gathered by associates and doctoral students eager to affirm my father’s work. Some researchers said that they were unable to replicate a few of the fifty-plus studies done by my father and others in the field of S.P.A.

In the face of such criticism, my father remained sanguine. “If they’re going to nay-say the research,” he would respond, “they’ve got to come up with a different explanation to account for the results. The data speak for themselves.” The Psychology Today article maintained a sphinx-like neutrality about the implications of his work. “The closest thing to a consensus about Silverman,” the article concluded, “is that final judgment must wait.”

But, as it turned out, there wasn’t time. Four years later, at age fifty-six, my father drowned. He had been swimming alone in a pond on Long Island. It was a few days after I had left for my sophomore year of college. We never learned his exact cause of death, but it seems likely that cardiac arrest was to blame. His presentiments had been right, but all those garlic pills and pulse recordings had done nothing to save him. He left behind reams of material—unfinished articles, ideas for future research scrawled on paper scraps—and a family devastated by his loss. I remember humming to myself during his funeral service.

The irony of his death is never lost on me. All those years growing up, we were focussed on the inevitable disappearance of the good mother of infancy, the separation from the primary caretaker that MOMMY AND I ARE ONE was supposed to redress. But we were all gazing in the wrong direction, soothing ourselves with fantasies of maternal plenitude when it was our father who would slip away.

With his death came the end of his research and, soon after it, experiments in S.P.A. more generally. In 1990, one of my father’s primary collaborators, Joel Weinberger, helped to conduct a meta-analysis of all MOMMY AND I ARE ONE experiments performed both in the United States and abroad. He later described the results as “reliable, of respectable strength, and . . . of comparable magnitude whether conducted by Silverman-associated or independent labs.” My father’s critics were unconvinced—as one psychologist observed, “Despite this strong evidence, many researchers remain skeptical about the SPA result.” In any event, the debate petered out as S.P.A. research was replaced by studies in implicit memory and automaticity—forms of information-processing that are unconscious without the lurid eroticism of Freudian theory.

When I think of the current attention to pristine automaticity over raw aggression and appetite, I can’t help but feel a sense of loss. The Freudian unconscious can be crude, a blunt instrument with which to make sense of everything from a bad day to irritation at a parent. But it’s also the only intellectual framework I’ve found to explain the inexplicable: a burst of sadism, free-floating anxiety, the will to self-sabotage. I miss my weird, messy father, but I also miss the thing he devoted his life to—the weirdness and messiness of unconscious fantasy, whose primacy these days, despite a recent resurgence in some therapeutic circles, has been overtaken by “problem-solving,” cognitive behavioral therapy, meds.

Perhaps that’s why, some thirty-five years after his death, I’m still keen to defend my father’s interest in Freudian theory. Not all of it, of course. Freud’s reductive developmental stages, as well as his damning views on femininity, I would happily leave behind. But the formative terrain of childhood, the concept of ambivalence, the centrality of unconscious desire and aggression—all still influence the way I look at the world.

One of my sons inexplicably forgot the passcode to his phone a while back, and we spent hours not just trying to recover it but also trying to understand why he forgot it in the first place. Because surely the unconscious was at play—nobody just “forgets” the passcode that they’ve regularly plugged into their device for three years running. When my son recalled that the passcode was an amalgam of his grandparents’ birthdays, I believed that I had figured it out. Two months earlier, my son had told our immediate family that he was gay, but he had been reluctant to share this more widely. “Your grandparents are visiting this weekend, and forgetting your passcode could reflect anxiety about keeping your sexuality hidden from them,” I suggested. My son ignored me, of course; he is about as receptive to psychodynamic interpretations as I was at his age. But I continue to offer them anyway. Having been raised in a household where plumbing one’s unconscious was seen as essential for psychic health, I have the sense that not encouraging my kids to do the same would feel like a form of neglect.

It’s been so long since my father died: the photographs have all faded, and the cassette tapes that he placed in our rooms while we slept are mangled with overuse. But conjuring up the Freudian unconscious in conversations with my kids keeps him close. During these talks, the air buzzes with obscenity—with references to sex, sadism, and scatology. Maybe this is my father’s legacy: not just subliminal messages and humming but also plain unvarnished talk. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com