Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

When I was growing up, the Sunday comics section of the local newspaper included a visual illusion similar to a Magic Eye. It looked like a circle made up of other, smaller, multicolored circles. The trick was that if you held the page close to your face and then pulled the page slowly away from you, an image would emerge with unshakable clarity: a cat curled up on a table, pushing through blots of orange and blue; a lush farm landscape, jutting up from small dots of green and red. Even if I looked away briefly and then looked back, the image would remain. As a child, I was fascinated by this mechanism, and I remain fascinated by it in a larger sense—the idea that something or someone can ignite our looking in a way that makes the seemingly quotidian come newly alive.

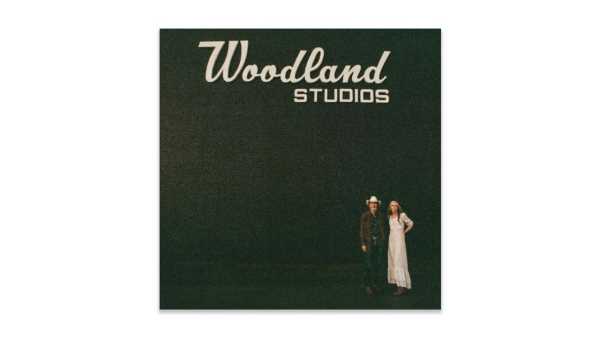

The songs of Gillian Welch and David Rawlings do this for me. For more than two decades and in the course of seven studio albums, the duo has written music that zooms in closely on a scene, a moment, a life, and then slowly pull the lens back, revealing a new vision, new coloring in a landscape, some specificity that adds narrative propulsion. “Woodland” is only the second album, after “All the Good Times,” from 2020, to be credited to both Welch and Rawlings. But the pair’s collaboration dates back to Welch’s 1996 début, “Revival”; Rawlings has played guitar and bass, added vocals, and co-written songs on all of Welch’s albums since.

Welch’s musical and writing bona fides were developed early in life. She was born in New York City and adopted by two musicians who were also comedy entertainers. The family moved to Los Angeles when Welch was three years old; there, her parents wrote music for TV, including “The Carol Burnett Show.” As an elementary-school student, Welch performed folk songs at community shows with her classmates. In college, after playing in louder outfits—a goth band, a psychedelic-pop group—Welch heard a record by the Stanley Brothers and had an epiphany about the kind of music she wanted to make: restrained, thoughtful, dense with storytelling. Her albums have consistently been praised for these very traits. In 2018, Welch became the first musician to win the Thomas Wolfe Prize for Literature.

She and Rawlings met in Boston, where they both attended the Berklee College of Music. They joined Berklee’s only country-music band before both moving to Nashville and starting to sing together more regularly. A Welch and Rawlings song gives the listener a feeling of walking into a room where a conversation has been ongoing—one that, despite your late arrival, you can easily join. There are recurring images: of the sky, of animals, of the land, of people trying to survive just as maybe you were moments before you started listening to these tracks. “Woodland” opens with “Empty Trainload of Sky,” which is marked by the rich sonic nuances that are present in all Welch-Rawlings arrangements. There’s Rawlings’s pinpoint, methodical guitar playing, the slightly elongated notes that roll steadily underneath all other instrumentation until surging momentarily to the forefront and then retreating back again underneath the noise. Like many songs in the Welch-Rawlings œuvre, “Empty Trainload of Sky” is not covering a lot of temporal ground. The speaker is simply describing a moment spent watching a freight train. “Just a boxcar of blue / showing daylight clear through / just an empty trainload of sky.” Through this process of staring, at a slow-moving train with daylight leaking through it, Welch finds small revelations, a temptation to fly upward, toward “the Devil or the Lord,” seeking some spiritual illumination that doesn’t arrive. Its lack of arrival doesn’t diminish the song, which ends with a repeated loop of “just an empty trainload of sky”—confirmation of what was seen, even as it has already faded, and with it the dreaming that it evoked.

Speaking of dreaming, “Woodland” is an album concerned with dreams, or visions, or reaching back toward past things that no longer exist. It’s an album steeped in longing, an emotion not entirely unfamiliar to the Welch-Rawlings universe but one that the pair has not usually mined in as much depth. “What We Had,” the album’s second track, with a swelling string section arranged by Rawlings, opens with Rawlings singing, “All my world is changing / I don’t know where I’m going” and continues in this vein, like a person feeling around in a dark room for a light switch. There’s a warmth to the longing that permeates the record. Someone is searching for something that you, a witness to their searching, are really rooting for them to find.

Even tracks that ostensibly hover around a feeling of satisfaction contain a layer of longing for that which has slipped away. “North Country,” a beautiful and sparse tune built around the traditions of a travelling song—one in which a person begins somewhere or moves toward a somewhere that is not her traditional place. In so many such songs, the lyrics evince a clear understanding of what sets someone off on the road—family, impending death, a beloved somewhere else. “North Country,” instead, offers a slow reveal: the song’s first section uses only the “I,” with the speaker singing about how cold it is up north, colder than Tennessee, how the season has to soften now before a trip is made, owing to age, to a thinning of the blood. Midway through the song, a first-person plural emerges: “We used to steal away and watch the fireflies after dinner.” It’s a brilliant songwriting gesture, centering the self and the ravages of time before, in one line, opening suddenly out to encompass the person who is both there and not, the person being reached for. In the song’s final act, the aching is clear. The singer can’t stand the winter, and the beloved loves the cold. Their paths will never cross again—unless, of course, the beloved grows weary of freedom up north. But who knows, really. Maybe they’ll just drift through mismatching seasons.

For writers who are so musically and lyrically precise, and committed to a tightness and neatness in their sounds, Welch and Rawlings are surprisingly unconcerned with closure. In these songs, living means reckoning with a sense of irresolution—with a series of questions echoing into the dark and returning to us unanswered. The song “Hashtag,” about the loss of a musician friend, ends with the lyric “When will we become ourselves?” When the voices of Welch and Rawlings intertwine, as they do throughout most of the record, it sounds like two people eagerly aiming to tell the same story at the same time, until their competing stories become one sound.

There are only ten tracks on “Woodland,” but there is a heft and a generosity to the album; each song feels like its own chapter of a book, and there is a specificity to the writing that furthers this sense. In “Here Stands a Woman,” there is not only a girl coming up from Danville but one whom we know, whose hair wears “that Danville curl.” I am not familiar with this style, but I feel familiar with it now, because I’ve also been invited into the world of her mother, her father, and the pearls she pawned once. These songs are literary experiences but also visual ones reminiscent of those old Sunday cartoon pages. You saw what you thought was a train, but it was also the open sky. And now you step back, and nothing looks the same as it was before. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com