Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In “Menu-Plaisirs—Les Troisgros,” Frederick Wiseman’s four-hour documentary about a great French restaurant, playing at Film Forum, there is a kitchen like none that I’ve ever seen: a large rectangular room with windows facing the woods; rows of stainless-steel countertops, with burners embedded in the flat surfaces; clear open air above the cooking spaces—a startling absence of ladles, pots, pans, mitts, and hoods (the high ceiling works as a hood). One further absence, and a very welcome one, too: a sweat-stained studly cook, hair enshrined in a bandanna, bullying everyone in the room.

In this airy space, everyone can see everyone else, and the young boss of the kitchen, César Troisgros, a slight, concentrated man with wire-frame glasses, controls the room with a look here and there, a quiet command, and occasionally a quick rush from one counter to another. We are about forty-five miles northwest of Lyon, in rural Ouches, where the Troisgros family runs an extraordinary restaurant called Le Bois sans Feuilles (The Woods Without Leaves). The price of the set meal, for lunch or for dinner, is three hundred and forty euros, hors boisson. (Call it five hundred euros per person with a good bottle of local wine.) Ouches! Yes, but, having seen the movie, I’m quite sure that no one is being cheated.

As always, Frederick Wiseman works against cliché—in this case, the clichés of TV cooking shows in which great food is produced by men of electrifying temperament. In the Troisgros kitchen, great food is a matter of craft, history, and dedication to an ideal, all of which may sound tediously high-minded, but which, in this movie, turns out to be thrilling. “Menu-Plaisirs” is one of the great Wiseman movies about work—the intentness and precision and quick-handed skill that produce such things as aiguillettes de Saint Pierre à l’amande, which turns out to be slices of John Dory fish, arrayed in a layered circle and dressed with a special sauce. The dishes are small and delicate, each one a complicated amalgam of traditional French cooking, Japanese aesthetics, and the practices of la nouvelle cuisine. Without anyone quite explaining it, we can see the doctrines that guide the establishment, carried out with moral fervor: cut back on cream sauces, use local vegetables, not much meat, cook things quickly in pans on high heat, keep the portions light and venturesome with a touch of acidic flavor. Working in this way, the main Troisgros restaurant has received Michelin’s highest rating, three stars, for the past fifty-five years.

Lyon is the gastronomic center of France, and, around this consecrated space, the Troisgros family has controlled one restaurant after another since 1930. At the moment, the family establishments include Le Central, in the small city of Roanne; and La Colline du Colombier, deep in the woods. Both places offer less complicated dishes (Côte de Cochon au Lassi de tomate) and less intimidating prices (fifty-five euros for lunch) than the mother ship with the wide-open kitchen. All three restaurants appear in the movie, though most of the picture was shot in Ouches. From scene to scene, we have to figure out where we are, since Wiseman, as always, tells us nothing—no explanatory titles, no maps, and no voice-over narration, either, though Michel Troisgros, the father of the kitchen master, César, explains a lot of the family lore and history to willing clients. Again, as always, Wiseman avoids tabular organization, moving instead through many scenes thematically arranged to comment on one another. What is the relation of authority to innovation? Can one honor tradition without getting smothered by it? And, also, a related question: Can the “King Lear” story ever end happily?

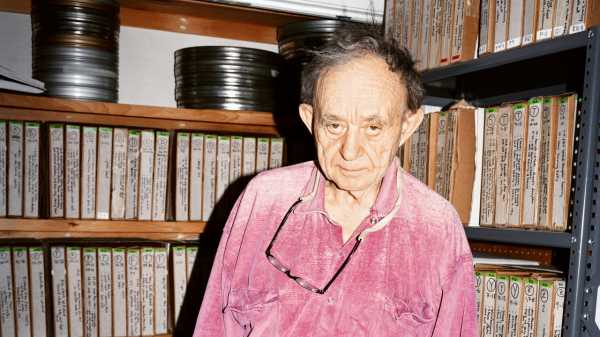

Frederick Wiseman turns ninety-four in January. He has been making movies since 1967—forty-seven films in all, most of them about American institutions: a racetrack, a hospital, an evangelical community in Aspen, a department store, a depressed American community in the Panama Canal Zone, an even more depressed fishing-and-canning town on the Maine coast. Has he left anything out? He actually filmed budget-planning sessions at U.C. Berkeley, not the most scintillating of milieux. A man determined to find out how things work, he has made films about city neighborhoods, retail establishments, monasteries, police forces, and night clubs.

In the early years, in such films as “Titicut Follies,” from 1967, about a facility for the criminally insane; “High School,” from 1968, on a soul-defeating public school; and the great “Welfare,” from 1975, about a New York welfare office, he dramatized American organizations that worked viciously against the people they were supposed to serve. In the left’s commentary on Wiseman fifty years ago, he was congratulated for his radical viewpoint. Lincoln Steffens with a camera! Wiseman entered an institution with a tiny crew, shot everything that interested him, captured about twenty-five feet of film for every foot in the finished movie. He took the place’s measure. The thematic elaboration, he always insisted, emerged in the editing, not in the shooting. The early films were tough and sardonic works enhanced by a poetic eye and by many nuances that the political commentators didn’t quite notice—a kind of black-comedy despair over life’s sheer orneriness, its refusal to conform to expectation.

The early political appreciation of Wiseman was inadequate, or at least limited, and he refused to be constrained by it. Even in one of his first movies—“Law and Order” (1969), a portrait of a mostly white Kansas City police force—the viewpoint was more melancholy than accusatory. The Kansas City police, at least at the time, were not so much oppressors of the community as armed servants of the last resort, attempting to intervene in situations—say, an incoherent family quarrel—that had drifted past the point of social breakdown. Watching the police make mistakes, we realized that many other institutions had failed these “clients” before the cops moved in. It was not an easy film to watch, but it challenged the anti-police cant of the time.

Even in the most tangled and unhappy places, Wiseman found noble and kindly gestures, small outbreaks of fortitude and courage—for instance, a doctor gentling a panicked elderly patient in the big-city “Hospital” (1970). Some of these moments, despite Wiseman’s refusal to comment, were packed with more emotion than one could easily handle. In “Blind” (1987), a sightless child eager to show a piece of work to a teacher climbs down a staircase, the camera following after him. It is one of the cinema’s epic journeys, and beyond heartbreak. Here was a filmmaker drawn to hard-pressing human realities impossible to summarize with an easy attitude of any sort. In trying to understand Wiseman, one drew on Dickens, Kafka, and Beckett rather than on the standard texts of social protest. He filmed the underside of an institution and its public face—the low hum of ordinary days, the sullen backwash of furious events, the torn-up betting tickets on the sticky floor of a racetrack after the race was over. In Wiseman’s hands, institutions developed a soul, even an unconscious.

Twenty years ago, he moved to Paris. He still makes films in the United States—a very benevolent portrait of a chatty multi-ethnic Queens neighborhood (“In Jackson Heights,” from 2015)—but his interests have begun to shift. There have been films about the Comédie-Française (1996) and the Paris Opera Ballet (2009) and London’s National Gallery (2014), and also a monologue film, “A Couple” (2022), in which a single actress recites Sophia Tolstoy’s unhappy journals in French as she moves around a luscious Brittany garden. The forest setting, with its lilies, frogs, and bending trees, doesn’t connect with Tolstoy’s laments, but so what? The splendor of the garden was a reward that Wiseman gave to himself and to the audience. Having stared into the abyss often enough, he now wants conditions of peace and order; he wants to film institutions that work well, especially French institutions that insist on historic continuity and also bounding artistic ambition.

What is the working day of a great restaurant? How do you get to the John Dory layered onto a dish? “Menu-Plaisirs” begins in the early morning. Young César and his brother Léo, Michel Troisgros’s two sons, meet at an open-air market. They buy aromatiques and kohlrabi and an oyster mushroom as big as a football helmet. Father and sons then meet at a table at Le Central. The restaurant is empty; they can talk. What fish will they need in the coming days for quenelles? Pike, perch, zander? Should the sauce for the white asparagus include almonds? Pureed or flaked almonds? And much more. The running of a gourmet restaurant is a complicated business—something we might have assumed, but it’s good to know that you have to create new dishes if you want to hold on to Michelin’s three stars and the clients’ interest. There’s sturdy debate on the almonds.

The clients themselves—mainly wealthy French families—have their crochets and intolerances, which the staff reviews several days before the diners show up. “They’re coming for Monsieur’s sixtieth. Be aware that they specified no lamb, no mutton, no rabbit, no game, no offal, no pigeon”; a little boy will replace his main dish with frog, a substitution one can imagine happening only in France. The clients have strong ideas about wine, some seriously considering bottles that cost ten or even thirteen thousand euros (“C’est fou!” say Michel and his wine steward—It’s crazy!), so the restaurant’s cave, which has more than thirty thousand bottles, may need replenishing. We later see Michel and his sons tasting and spitting some new varietal in the underground vault.

Wiseman visits the local farms that the restaurant draws on. The farmers volubly insist that the soil must be nourished (but not with fertilizer) or the white Charolais cows won’t taste right, the grape won’t taste right. A pedantic cheese ripener, responsible for wheels from all over France, explains that cheese must be dehumidified and then stored to ripeness and humidified all over again. (“I ripen cheese. I don’t dry it out.”) The nouvelle cuisine, we realize, joins the latest agronomic science to respect for the incomparable French soil, le sol vivant. Now and then, Wiseman pauses the restaurant routines and the lecturing farmers with still shots of the countryside—pastures and hills and clouds in south-central France, nothing spectacular but in this context as moving a pastoral vision as the cinema is likely to give us. Wiseman’s contentment is not passive but charged with purpose: the movie convinces us that this great restaurant couldn’t exist anywhere in the world but here.

The Troisgros family bought the rural Ouches property in 2014 (Michel’s wife, Marie-Pierre, runs a hotel next to the restaurant), and, with the help of the designer Patrick Bouchain, built the big kitchen and an accompanying dining room from scratch. A friend of mine who knows about such things says that modern French design can be awful, but the dining room is a stunner—another large open space, this time with oval blond-wood tables, positioned far apart from one another, the floor-to-ceiling windows offering a view of trees, fields, and horses. When the place is packed (sixty people), the restaurant noise rises to a loud murmur. In all, Wiseman seems to have arrived at the Great Good Place. The miracle of the Troisgros style is that the mastery we see of scaling, scoring, fluting, scalloping, whisking, and cooking forbids pretension of any kind. Pride, certainly, and poise—even the waiters have it—but no boasting. The chefs, the cooks, the waiters all concentrate on the task at hand, often in silence, and their absorption passes on to us. Wiseman excels at patience, often filming troubles and suffering at length. In this movie, he films pleasure and inspired labor at length.

The tempo of the kitchen increases when the house is full, though a certain genial informality prevails in the great dining room. The staff come out of the kitchen and speak to the clients, especially Michel, a man of sixty-five, a little stout (how could he not be?), rapid and decisive. Michel is happy with the four-generation family rule, happy with his own role in it, but ruefully certain that he must give over management of the restaurant to César. He knows what it is to be dominated—Pierre, his father, and one of the inventors of the nouvelle cuisine, lived to the age of ninety-two.

Yet Michel, benevolent as he is, does not actually want to let go, and his needs, his restless brilliance, his desire to stay on top, run through the movie. When a young cook blanches some brains before removing the blood vessels, Michel irritably pulls down heavy volumes of Escoffier and Larousse. Sometimes, the old books still matter; he makes the boy read the appropriate passages of classic wisdom. In a reverse situation, there is a prolonged high-comedy sequence of Michel trying out a new dish of kidneys with a passion-fruit sauce concocted by César and a cook. Michel complains that the strange dish is too hot, his mouth is on fire, it needs more salt, there’s too much Sriracha in the reduction, and so on, yet he cannot stop eating kidneys, revising the dish as he consumes it, refusing to yield control over the recipe. “Strawberry and caviar?” he asks as another new dish is proposed. “Caviar as a dessert is unheard of,” but then he hears of it. Restaurants this great can survive only by melding tradition and invention, even initially absurd invention.

An end crawl (rare in the Wiseman canon) informs us that César has, in fact, taken over. The soil has to be renewed in order to stay the same, and so does the restaurant. New dishes will be created, and the family enterprise will continue, perhaps forever. Wiseman has found an institution that works splendidly, and he seems satisfied—until, in his tenth decade, he moves on to the next project. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com