Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In the early nineteen-eighties, Gail Butensky, then an undergraduate at Northwestern University, in Chicago, started taking photographs of punk bands for the Daily Northwestern. “I had pretty wimpy taste in high school,” Butensky told me recently. “But in the late seventies, when I heard artists like Patti Smith and Talking Heads, my outlook changed. I got much more interested. I met my first friend in college because he had a The Jam button on his lapel. Back then, that was how you found your people.” Butensky’s spontaneous approach to shooting musicians matched the scrappiness still inherent to punk and indie-rock, genres rooted in a kind of contrarian, D.I.Y. ethos—less “Fake it till you make it” and more “Fuck making it.” “If I didn’t have an actual press credential, I usually either knew the band or knew someone at the club,” Butensky said. “I never worked in a studio, never used lights. It was punk rock on the go. Even when I thought, Maybe I can do this for a living—which never happened—I always knew it would only be on my terms.”

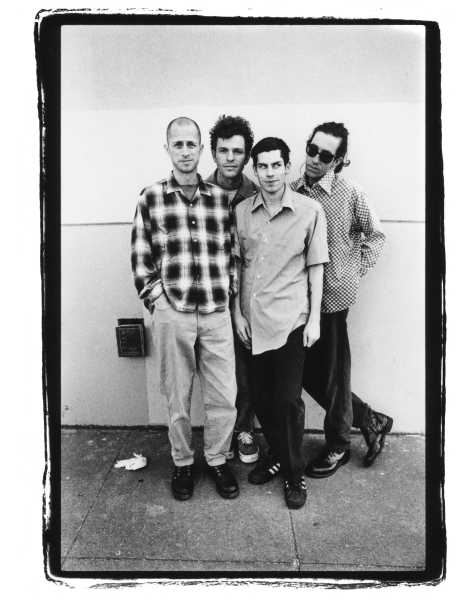

The Mekons, 1989.

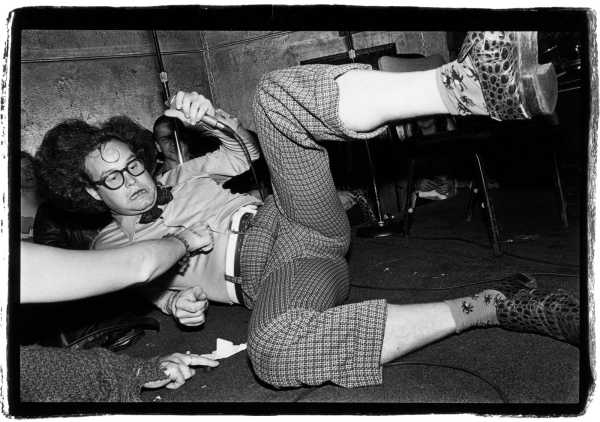

That Butensky never quite professionalized this work, beyond the occasional check from an alt-weekly or an independent label, feels spiritually apropos. Her images of bands such as Butthole Surfers, the Mekons, Hüsker Dü, Pavement, the Fall, Minutemen, and others are unusually raw and intimate. Perhaps there was no other way to authentically present artists who were so disinterested in genuflecting to corporate machinery. Dressing and posing a group as lawless and refractory as Butthole Surfers—Butthole Surfers—is a laughably incongruous idea, though it is possible to dig up later images of the band members semi-obediently standing in a line, their faces anodyne and plain. Those pictures feel silent. Whereas Butensky’s image of the vocalist Gibby Haynes, his shirt mostly yanked off but still dangling from his wrist, yowling into a megaphone at CBGB, is so visceral, so fierce and deafening, that it makes me want to turn the volume down on some invisible speaker. (Excavated footage of this particular show suggests an unruly and volatile crowd, one very pissed-off man hollering “Get the hell out of here!” before the band even began to play—God bless.)

Minutemen, 1985.

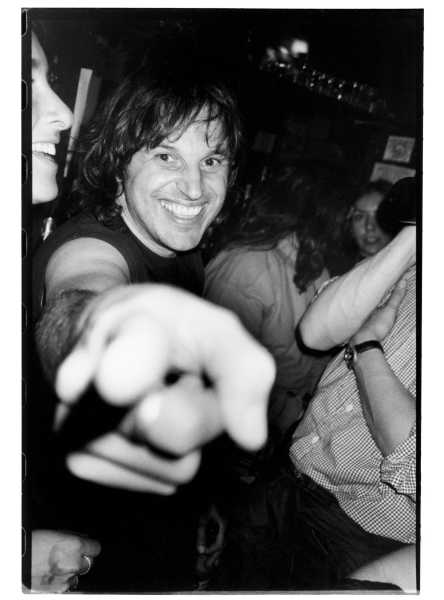

Hüsker Dü, 1993.

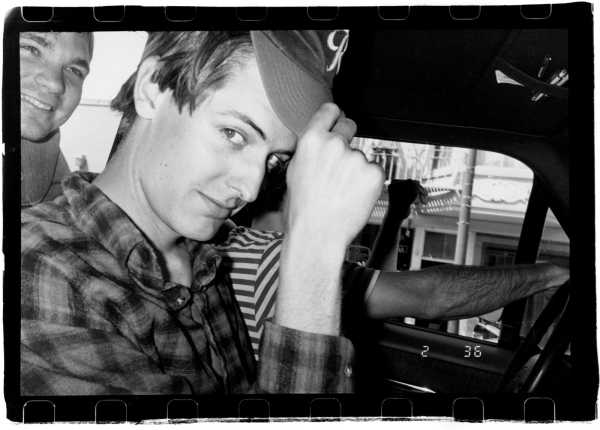

Stephen Malkmus, 1992.

There’s unbelievable warmth to Butensky’s photographs from this era. Though this music is often beautiful, it is not exactly tender, and its dissonance can be intimidating; what I find consistently poignant about Butensky’s work is the way in which it allows for something goofier, softer, and more playful to be made visible, without betraying the prickly ideals of the scene. Here is Stephen Malkmus of Pavement—a king among the über-serious, crossed-arms indie-rock set—looking cute and sweet and boyish, riding around his home town of Stockton, California, with his friends. “I think ‘Slanted and Enchanted’ had just come out, or was about to,” Butensky said, of the Pavement shoot. “The band was going to be on the cover of the SF Weekly. I can’t remember if the band or Matador Records had asked for me, but I borrowed my roommate’s car and drove to Stockton for the day. They showed me all around their town. Miniature golf, we had lunch, I think we played Skee-Ball in a bar. And all the time I was taking photos. That was my favorite kind of assignment.”

Pavement, 1993.

Butthole Surfers, 1985.

Chris Knox, 1993.

Before she graduated college, Butensky helped launch Matter, a punk zine whose contributors included the producer and guitarist Steve Albini, of Big Black, and Ira Kaplan, of Yo La Tengo. Butensky would continue to collaborate with Albini, ultimately making album art for several Big Black releases. In one photo, shot in 1986, Albini, the guitarist Santiago Durango, and the bassist Dave Riley are piled into the back seat of a taxi, en route to a gig at CBGB. They look grave, determined. “I lived in a loft down on Water Street,” Butensky said. “I hadn’t been back in New York City for very long, and I was still very connected to all my Chicago folks. A lot of them passed through and stayed over. Big Black was in town for the weekend, so they stayed at my loft, and I showed them around town. I don’t remember if we were trying to specifically take promo shots, or if, as usual, I just started shooting. I used to walk around New York with a lot of cameras—heavy Nikons—because you never knew who you would see.”

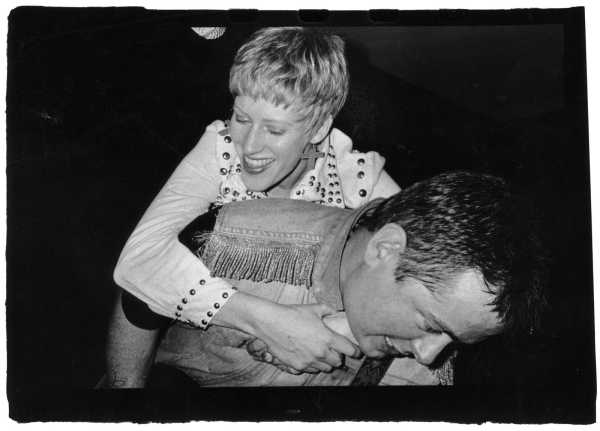

Bikini Kill, 1992.

Fuck, 1997.

Mark E. Smith in the Fall, 1983.

Big Black with Steve Albini center, 1986.

Albini and Butensky met at Northwestern. “There was a crowd on campus, basically the folks that weren’t into football or in the frats and sororities,” Butensky said. “I remember a party at my off-campus house, and a conversation where Steve was arguing that the only good Beatles song was ‘A Day in the Life.’ College talk! And he usually wore pajama tops as shirts. Not sure why I remember that or if it’s even true.” In 1983, Butensky went to see the Birthday Party—a lawless, incendiary, and gorgeously perverse punk band fronted by a then-twenty-five-year-old Nick Cave—perform at a bar in Chicago called Tuts. Two months later, the Birthday Party would break up. Butensky’s photo of Cave from that night—positioned between two blinding lights, his fingers stacked with gold rings, one arm stretched into the air, eyes narrowed—is arresting. He looks messianic, intense, slightly deranged. “Pretty sure we all had a feeling this show was going to be somewhat epic,” Butensky said. “They were legendary in the underground. I had only been taking photos seriously for a few months, so they were really one of the first bands I shot live. And you could get up close in a small club. I remember looking at the contact sheet in the office of the Daily Northwestern the next day, and Steve—maybe he wrote the review?—saw it and said, ‘That’s the shot.’ ”

Nick Cave in the Birthday Party, 1983.

Three Day Stubble, 1992.

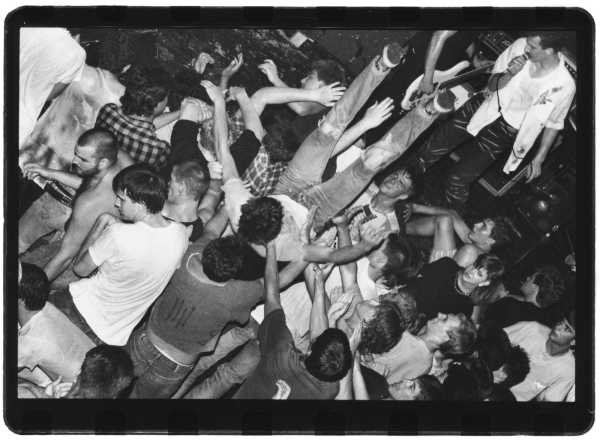

I asked Butensky how she managed to elbow her way to the stage. Navigating a swirling, testy pit at a punk show is not an especially peaceful endeavor, especially with a camera. “I’ve been told I could be intimidating,” she said. “I’m barely five feet three but found that worked to my advantage. I tried to be nice about it,” she added. “No pushing!”

Naked Raygun, 1984.

Sourse: newyorker.com