Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Since Edward Burtynsky’s birth in Ontario, Canada, in 1955, the Earth’s population has roughly tripled, and its economy has grown tenfold. This “great acceleration,” to use the title of the (exquisitely curated and hung) retrospective newly installed at the International Center of Photography, on the Lower East Side, is the most anomalous stretch in human history, and during the past four decades Burtynsky has been almost certainly its greatest visual chronicler—a poet of scale, making use of ever-better lenses and innovations such as drones to gain an ever more encompassing perspective. Perhaps the only photographer to have backed up farther from this subject was Bill Anders, the Apollo 8 astronaut who gave us “Earthrise,” in 1968. But that image was taken from too far away to even hint at the stress that the Earth was undergoing as the human footprint expanded. Burtynsky had the perfect depth of field for the task, and his images have become steadily more complicated over time.

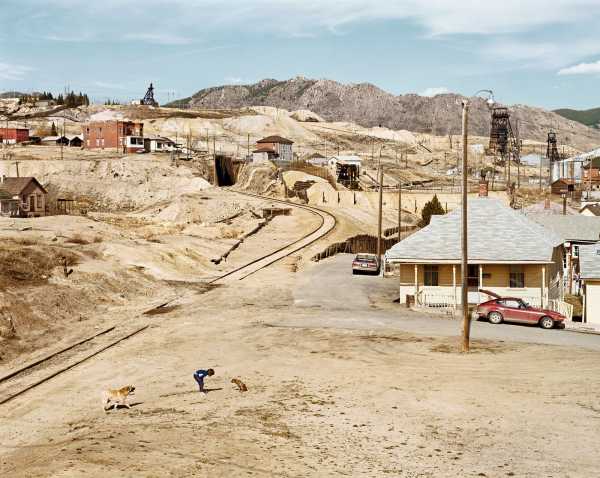

Homesteads #29, Walkerville, Montana, U.S.A., 1985.

Dryland Farming #27, Monegros County, Aragon, Spain, 2010.

Consider, for instance, “Mines #23,” a study of a copper pit in Utah, from 1983. Already the sense of geological proportion is emergent; it takes a moment to orient yourself and understand that the tiny trucks in the middle of the scene are actually gargantuan earthmovers. Or “Quarry #1,” a 2016 study of the Italian mountainsides where Carrara marble is extracted—it’s a masterpiece of geometry and brooding color that reminds me of Bruegel’s great “Tower of Babel.” But it’s “Dry Tailings #1,” from another copper mine, this one in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which really establishes the dilemma of our age. At first, it seems to be a study in hue—the ochres, tawnies, pinks, and roses that the mineral-rich soil produces. But, if you look closely, you can see minuscule human figures that both reveal the scale and illuminate the drama—these figures are emerging after hours, to illicitly comb through the tailings in search of small chunks of the cobalt that helps power cell-phone batteries. Perhaps it will remind you, as it did me, of Sebastião Salgado’s indelible images of Brazilian gold miners climbing the sides of a pit, from the nineteen-eighties. Salgado, who, until his death in May was a close friend of Burtynsky’s, focussed quite literally on the human cost of the acceleration; Burtynsky’s concentration on the landscapes being ravaged makes their combined works an irreplaceable diptych.

Dry Tailings #1, Kolwezi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024.

It’s not that Burtynsky can’t photograph bodies and faces—tender portraits, such as “Shipbreaking #14,” part of his series on the almost unbelievable story of the Bangladeshi men who dismantled retired oil tankers by hand, show that he connects quite easily on the smaller scale with people in his vast world. But it’s the vastness that’s his true subject.

Shipbreaking #14, Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2000.

Look at his account of agriculture and farming, which has altered more of the Earth’s surface than any other activity. There’s almost never a farmer in sight—instead, it’s the sheer size of the industrial enterprise that draws his eye. The largest print in the show, at twenty-eight feet by twenty-eight feet, is titled “Pivot Irrigation #8,” and was taken from a helicopter hovering thirty-five hundred feet above the high plains of Texas. Framed almost formally by perfectly squared-off farm roads, it shows the giant circle of fertility that comes from sprinklers drawing on the (depleting) Ogallala Aquifer beneath; the detail is so fine that you can stare at it for an hour, constantly noticing new details (combine tracks turning at the edge of the irrigated circle, say).

Pivot Irrigation #8, High Plains, Texas Panhandle, U.S.A., 2012.

In other images, people are present but rendered almost as parts of the great machine that powers the acceleration. “Manufacturing #10b,” shot in 2005 in Xiamen City, captures, like no picture I have ever seen, China’s extraordinary economic surge as the millennium began. The ranks of yellow-clad workers disappearing into an almost infinite distance are all assembling drip coffeemakers.

China’s relentless rush is captured in other images, perhaps most powerfully in “Feng Jie #4,” which shows workers in 2002 racing to disassemble the city where they lived before it would be drowned by the Three Gorges Dam, which has the greatest generating capacity of any dam in the world. What at first seems to be undifferentiated rubble are actually piles of bricks, carefully numbered so that their owners can be compensated; in the background, a roving troop of boys follow leaders hoisting brightly colored flags as they scavenge for wood that might someday float up and damage the turbines; their bonfires brush smoke across this battlefield scene.

Manufacturing #10b, Cankun Factory, Xiamen City, China, 2005.

Railcuts #1, C.N. Track, Skihist Provincial Park, British Columbia, Canada, 1985.

If China marks the culmination of this unending fire of expansion, America set the spark, with oil as its most important accelerant. Burtynsky tells this story with remarkable economy and depth. It begins with production: “Oil Fields #19a,” his image of the pumpjacks—also known as nodding donkeys—spreading out far across the sands of the San Joaquin Valley, documents the site of one of the early American strikes and so goes nearly to the origins of the petroleum age.

He also documents the life that crude produced. In “Highway #5,” a helicopter view of Los Angeles bisected by one of its great freeways, you see the (prosperous) sprawl limited only by the mountains on the horizon. In one of his most famous images, “Breezewood, Pennsylvania,” from 2008, you sense the tawdry but real joy of America on the move; it’s an image, shot from a bucket loader in a motel parking lot, of a typical highway interchange, with a Shell station and a Starbucks sign in the center of your gaze. “Coffee keeps us going,” he explained. “Gas keeps the car going. It’s all the things that keep us in motion.”

Breezewood, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 2008.

And the thrill of that motion comes through in a particularly striking photo, “Talladega Speedway #1,” which captures the 2009 running of Alabama’s greatest stock-car race before a crowd of eighty thousand people—Burtynsky’s image is so sharp that you feel like you can make out each one of them, standing at attention as the national anthem plays, a tractor-trailer carries the flag around the track, and a squad of military jets flies overhead. Burtynsky doesn’t flinch at showing the aftereffects of all this combustion: “Auto Wreckers #1” documents a car graveyard in the sands of Tucson, and “Oxford Tire Pile #1” captures a corner of a giant tire dump in Westley, California. (Shortly after he shot the image, in 1999, a lightning strike started a fire, which burned for a month, reducing the tires to the oil used in making them.

Salt River Pima and Maricopa Indian Community / Suburb, Scottsdale, Arizona, U.S.A., 2011.

Oxford Tire Pile #1, Westley, California, U.S.A., 1999.

If there was one absence in Burtynsky’s account of our time, however, it was the single greatest result of all that mining, burning, and consuming: the transformation of the atmosphere. Nothing else comes close in scale to the chemical disruption of the air—the flood of CO2 now rapidly overheating the Earth and producing a series of changes so titanic they dwarf even the forces that these photos depict. But carbon dioxide is invisible, which is a problem for photographers.

That’s why in some ways the most remarkable image in the whole show is the most recent, taken too late even to be included in the catalogue. Hanging next to the I.C.P.’s cash registers, and perhaps easily missed as you buy your ticket, the image is an aerial view of the damage from January’s Palisades Fire in Los Angeles. In the photograph’s pinprick sharpness, the few big houses that survive stand out on the fringe of hills at the edge of town. “These were monster homes,” Burtynsky told me, and, indeed, the Palisades blaze is one of the first examples of climate change coming straight for the rich as well as for the poor. The photograph was taken six weeks after the conflagration, and you can see the first lots being cleared of rubble, and the cars flowing by again, but it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the gargantuan drama Burtynsky has spent his career depicting is here nearing its end.

Uranium Tailings #12, Elliot Lake, Ontario, 1996.

Sourse: newyorker.com