Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Diane von Furstenberg has been putting on The Diane von Furstenberg Show for something like half a century. Act I began, roughly, in 1969, when Diane Halfin, twenty-two years old and three months pregnant, became Princess Diane von Furstenberg, wife of the German playboy Prince Egon von Furstenberg. The couple stormed New York, where they were an exotic fixture on the social scene. In Act II, as a decadent ex-princess and fashion juggernaut, she was the famed inventor of the wrap dress, an emblem of liberated seventies womanhood. (Her best model was always herself.) More acts flew by: Studio 54 habitué, Paris literary impresario, nineties QVC queen. In 2001, she married the media mogul Barry Diller, years after they had first dated, in the late seventies, and became part of yet another endlessly scrutinized power couple.

At seventy-seven, von Furstenberg is still starring in the spectacle of her life, now as a global luminary with wisdom to dispense. She has told her story, and doled out advice on living well and being fabulous, in multiple books (“The Woman I Wanted to Be,” “Own It: The Secret to Life”). Since 2010, she has bestowed the DVF Awards to “extraordinary women who are dedicated to transforming the lives of other women,” which is very much how she would like to be seen in her latest act. A new Hulu documentary, “Diane von Furstenberg: Woman in Charge,” directed by Trish Dalton and Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, retells the story of how a Belgian Jewish daughter of an Auschwitz survivor became a brand name. Along the way, she shares details of her rarified life (“I was with Warren Beatty and Ryan O’Neal on the same weekend—how about that?”) and reflections on getting older (“Age means living!”), with testimonials from the likes of Hillary Clinton and Oprah Winfrey.

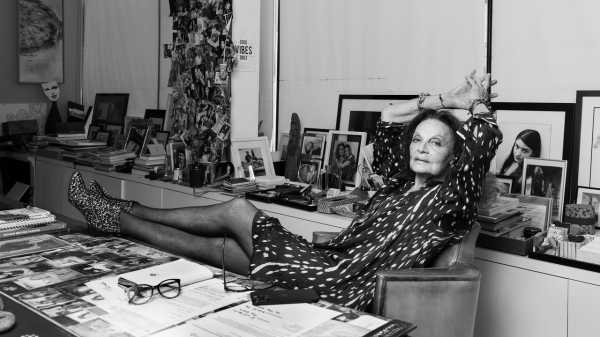

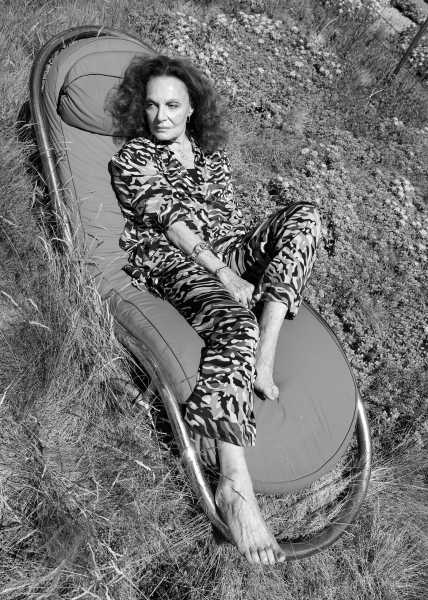

When I went to talk to her recently, The Diane von Furstenberg Show began several blocks away, as I entered the meatpacking district—the neighborhood that she and Diller played a central role in transforming from an industrial underbelly to a gentrified nexus of fashion, art, and tourism. On a cobblestoned corner of Washington Street, above her flagship store—her last remaining retail location in the United States, after her business nosedived during the pandemic—an assistant brought me into her headquarters, a high-femme corner office in dazzling colors: leopard-print carpeting, a Mae West Lips Sofa, a Takashi Murakami portrait of von Furstenberg lounging beneath cartoon flowers. I heard a voice from the hall: “I’m coming, yes?” Then she swanned in, heels clomping, in an all-business blazer over an all-pleasure floral top, with a necklace that read “in charge.” When I asked about it, von Furstenberg walked to the windows and returned with a card bearing the “InCharge” manifesto. (“To be InCharge is first a COMMITMENT TO OURSELVES. It is OWNING WHO WE ARE.”) As her personal chef prepared lunch, she draped herself over a white sofa with zebra-print throw pillows. The show was in full swing. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

So much has happened in your life that it’s hard to keep it all in your head at one time, much less in one movie.

I tell you, yesterday I was so down. I felt like a total loser. I said, “Why did I let everything out like that? I prostitute my family, I prostitute everybody, just hoping to be inspiring.” Then I came to the office in the afternoon, and my grandson and my granddaughter were there—they are twenty-five and twenty-three—and we cuddled, and we talked. We actually talked about sex.

This morning, I woke up and I was good. When I see my family—my son, my daughter, my five grandchildren—I say, “Well, I must have done something right.” Even though in the movie they say I neglected them.

Was there anything in the movie that surprised you or was difficult to watch?

I watched it twice. I didn’t want to see it until it came out. I met Sharmeen because I was giving her a Woman of the Year award from Glamour. She’s a formidable woman. Fifteen years ago, I created the DVF Awards, and I wanted to do a series of short docs about women who have incredible stories. No network wanted to take them. They kept on saying, “We would like a documentary about you.” And I said, “I don’t want to do that.” Finally, Sharmeen said, “Through you we can talk about the women.” So that’s how she got me to do it, but she didn’t talk about the women that much.

No, it’s really about you.

The minute that was decided, I said, “I don’t want to be a producer of my own movie. I’ll give you the access, but I don’t want it to feel like promotion.”

It’s the fiftieth anniversary of the wrap dress. What do you attribute its staying power to?

It’s true, I created the wrap dress. But also the wrap dress created me. It’s a combination of the fabric and the body language and the prints and the movements and da da da. And they’re indestructible. There’s always a new generation that discovers them.

I learned from the documentary that the wrap dress has an indirect relation to Watergate.

I had first created a wrap top with a matching skirt, and during Watergate Julie Nixon Eisenhower made a speech to defend her father—and she was wearing that wrap top. I thought, That should be a dress!

When you created the wrap dress, in 1974, were you responding to other trends in fashion?

No, I wanted to be independent. My first job was in Paris. I worked for a photographer’s agent, and that’s how I got involved in the world of fashion. I didn’t do anything but answer the phone to tell people he wasn’t there—either the photographers he hadn’t paid or the women he didn’t want to see. I had my boyfriend, Egon, who I met at university in Geneva. He invited me to his house in Cortina. In Cortina, I met the father of a friend of his brother, and he invited me to come to his printing plant. I just watched. I never got paid or anything. But it was interesting: buying illustrations, how you turn it into a fabric. This man, Angelo Ferretti, bought another factory, because he needed more room. There were all these machines that were making stockings, and he used this machine with a thicker yarn and made jersey fabric. I went, Wow, maybe I can make samples! But I was still very shy.

Then I went to visit Egon, and I discovered New York. I said, “I have to come back here. What can I do?” I went back to Italy, started to work. In between, Egon comes to Rome, we meet, we get engaged. Before I know it, I’m pregnant. I go to Angelo Ferretti. I say, “I want to be independent. I don’t want people to think that I got married because I was pregnant. May I make some samples I can send to America?” [She calls to the chef.] C’est à table? [The chef answers, “Oui, c’est prêt!”] O.K., let’s go and eat.

[We move to a glass table in the center of the room, with a tall floral centerpiece. The chef brings out ground lamb, hummus, avocado-and-cucumber salad, and fennel. Von Furstenberg keeps a small buzzer at her side, with which she occasionally summons her staff.]

This is 1969, a major moment in your life. You’re pregnant with your first child and go to Geneva to get an abortion—

No, no. I went to visit my mother in Geneva. There was a doctor who we knew would do an abortion. At that time, there was no ultrasound, so to be pregnant was much more abstract. I told my mother I was pregnant. She said, “Did he give you a ring?” “Yes.” “Did you talk about marrying one day?” “Yes.” “So whatever you do, you have to make that decision together.”

Do you think about the course your life would have taken if you hadn’t had that baby, hadn’t married the prince, hadn’t become Princess Diane von Furstenberg?

It’s hard enough to figure out things that have happened. I have no idea. You aren’t actually in charge of your destiny. What you are in charge of is how to navigate the things that happen in your life. For example, my mother—I knew she had been to the camps. I remember she had two numbers [tattooed on her arm], because she went to two camps. But it was still very abstract. It’s only when I was in my thirties that, one day, the Anti-Defamation League was honoring me at the Pierre Hotel. It was what, 1980? I listened to the program, and at the end I got on the stage and said something that not only I had never said but never thought: “You all know me because of my wrap dress. But what you don’t know is that, eighteen months before I was born, my mother was forty-nine pounds, in Auschwitz.” This was a major turning point in my life, because I realized it was my responsibility to talk about that.

How did your mother react to the fact that you were marrying into this German line of nobility?

First of all, she left my father sixteen years after she got married, and her boyfriend was Swiss-German. The main thing that my mother said was, “No matter what, you’re not a victim.” Esther Perel, you know who she is? We could have been sisters. She’s from Belgium, Holocaust parents. She told me, “There are two kinds of survivors: the ones who keep on complaining and remembering, and the ones who want life.”

Were your in-laws, the von Furstenbergs, more scandalized that you were pregnant or that you were Jewish?

Egon was half Italian—he was an Agnelli—and they were fine. Did the German side like to have a Jewish girl in their blood? No.

What are your strongest memories of your wedding day?

My father had hired an entire Russian band, with a violin and everything, and I was terrified he would sing. Which he did. But everyone loved it.

So then you and Egon became a New York It Couple.

Very It Couple. He was the It Person. People were very jealous that I married him. You can imagine: a young, beautiful, handsome prince, arriving in New York. All the girls wanted to marry him. And this little Jewish girl—why her?

What was your favorite part of being a princess in New York City?

I never used [the title]. I mean, I used it in Italy. One day, I was giving an award to Gloria Steinem, who became a big friend of mine, and as I was preparing my speech I remembered that I gave up being a princess to be “Ms.,” because she had invented Ms.

A New York cover story in 1973 was the breaking point in your marriage. What did you see in that piece that you hadn’t wanted to see?

Linda Francke was the writer. Jill Krementz was the photographer. They came everywhere. A picture of Egon in the subway and da da da. I was a young woman with a business that was blowing up. I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. I had two small children. My husband was super handsome, super promiscuous. We would go to cocktail parties and dinners and balls and gay bars, every night! We were juggling. So poor Linda, super feminist, comes. My mother-in-law was there, my mother, my father-in-law. She interviewed everybody. When the story came out, I realized that I cannot control what other people say. I can only control me. And I thought it was better that we separated. That was that. But we stayed good friends, always.

Did Egon see the article similarly?

Yes. Oh, my God, he called Linda and he said, “You destroyed my marriage!”

It’s interesting to think about you in the context of seventies second-wave feminism, because in certain ways you didn’t fit the mold. You wore fishnet stockings and heels and were very, as we might say now, sex-positive, which wasn’t necessarily—

Wait. What did you say? “Sex-positive”? What does that mean?

Thinking that sex is something that can empower women rather than subjugate them.

I am definitely sex-positive.

I was reading a Times story about you from 1977, which said, “It’s unlikely that she’ll turn up in Ms. Magazine as feminist of the year.” That made me laugh, because Gloria Steinem is in the documentary now, singing your praises.

I am totally a feminist. I have always been a feminist. If you’re sex-negative you wait for others to—I don’t know. I’ve never heard this expression, but I like it.

In that article, you’re quoted as saying, “Just because a woman’s smart doesn’t mean she has to look like a truck driver.” Did you feel like you were accepted by the feminist movement at the time?

I don’t know. I never asked them. I don’t think I’ve ever asked myself if I was accepted anywhere, actually. I don’t care about being accepted. I’m a feminist, that’s all that matters. And my dress became a symbol of liberation.

Right. You came up with the slogan “Feel like a woman, wear a dress!”

You want to know how that happened? Egon had been living in New York a year before me. You can imagine: European, aristocracy. He does a training program at Chase Manhattan Bank, lives on Park Avenue with a friend, goes out, blah blah blah. He knows everybody, so he organizes for me to go and meet Diana Vreeland. You know who Diana Vreeland is?

Of course, the legendary editor of Vogue.

So I arrive in her office, they roll in a rack. Whatever this office seems to you, that’s what it seemed to me. I was totally intimidated. I threw the clothes on the rack. She comes in. First thing she does, she lifts my face [with her hand]. Her assistant said, “She’s going to help you.” I said, “But what do I do next?” She said, “Market Week is when all the buyers come from all over the country. You list yourself in the Fashion Calendar and take a little announcement in Women’s Wear Daily.” The next thing I know, I go and take a picture to go with my little announcement. I sit on a cube. The pictures come out great, but there’s this big white spot.

On the cube you’re sitting on.

Right. So I said, “I should write something.” Without thinking, I wrote, “Feel like a woman, wear a dress!”

You seem to be very invested in the concept of womanhood. Where do you think that came from?

My mother. I realized so many things about my mother. She did not want to die. Right now I’m in contact with [Rachel Goldberg-Polin], the mother of an Israeli hostage, because I met her in Davos. She was not a victim. She was strong. The other day she was on CNN, and so I took a picture and I texted her, and I said, “My mother survived Auschwitz. Thirteen months of concentration camp. And she always thought that she came out because of the strength of her mother. So your strength is helping him.”

Your mother had a great attitude toward men, too. She called them “les pauvres.”

“Les pauvres” [“poor people”] means we have to be nice to them. My mother was very strong. She used to say, “God saved me so that I could give you life. By giving you life, you gave me my life back. You are my torch of freedom.” So I was born with a torch of freedom in my hands. It could be heavy for a little girl, but I took it. I owe everything to her.

After you broke up with Egon, what did you want in terms of men?

I didn’t want anything. I always went from one to another.

There’s a shot in the film of an album with Polaroids of men. Is that, like, your conquest book?

I have an album of everything. I’ve written my diary since I was a little girl. I take about a hundred pictures a day. As a matter of fact, I’m going to take a picture of you. [She snaps a photo of me with her phone.]

In the film, you tell the story of how you turned down a threesome with David Bowie and Mick Jagger. What went through your mind? What were the pros and cons?

Mick and David always competed with each other. They both pretended to speak with a Cockney accent, but they were boys from good families. So it was a play. I mean, it’s very flattering. Mick Jagger and David Bowie, at their prime. The whole thing was a joke. But I was thinking, Oh, that would be a really fun thing to tell my grandchildren. And then nothing happened. It became an even better story to say that I didn’t do it.

I’m interested in your Studio 54 years. Could you tell me about some of the people who were also iconic partygoers?

First of all, I was not one of these people who stayed there all night. I lived at home with my children and my mother. What I liked was to drive my own car, arrive, meet friends there. The entrance was huge, with long mirrors and disco music. It was a great pickup place. I never did drugs in the basement or anything like that.

Were you close with Andy Warhol?

No matter where you went, he was there. He was a pillar of New York at night. Andy went around with a tape recorder. He was taking pictures of you, he was taping you. He didn’t speak much. He was a spectator, not an actor. You didn’t have a long conversation with him, unless you went for lunch at the Factory.

Did you connect with any of his superstars, like Candy Darling?

It’s funny you mention that. I saw a picture of her at Gagosian this month. I didn’t know her well, but I was moved by her. I don’t know why. Maybe she was the first—what’s the correct word?

Trans person you met?

Mm-hmm. Andy was very generous to her. He took good care of her.

Did you ever intersect with Donald Trump when he was a young businessman on the scene?

I always snubbed him. Always avoided him. Never had a conversation. I left New York because people like Donald Trump had arrived.

Is it true that you spent four years in the eighties wearing sarongs?

[She thinks.] Yeah.

What brought you to that phase?

My mother had terrible trauma and ended up in a mental institution, briefly. That’s when I really realized for the first time what she had gone through. I wanted to go as far as possible, so I took the children and we went to Bali. And in Bali I met this Brazilian man who lived in a bamboo house. Sometimes you fall in love with people, but you really fall in love with love. And you fall in love with the fantasy.

What was the fantasy?

To be far away: jungle, volcano, nature.

Were you also running away from your life here, which had been very glamorous and high-profile?

I hope I never run away, but I went ahead somewhere. Then I left Paulo for an intellectual and had a publishing house in Paris. It was another fantasy. I wanted to be a writer’s muse, so I became one.

In 1992, years after you gave up control of your businesses, you were on QVC selling your fashions.

QVC was a discovery that both Barry and I made together. I discovered QVC, and then I brought him, and then he took control of QVC. And then we were back together.

I read that you love “Death of a Salesman,” which seems counterintuitive, but I guess on QVC you are a saleswoman.

When you sell, you’re always Willy Loman. I went around department stores selling dresses. I may have looked glamorous, but I felt like Willy Loman. Barry feels like a Willy Loman. I love that play. I love stories of salesmen and impostors—they’re my favorite characters. They’re very similar, in a sense.

Speaking of Barry, I went back and read Larissa MacFarquhar’s New Yorker Profile of you. There’s a line about your first relationship with Barry, in the late seventies, that I have to ask you about: “Once when they were at loose ends in Hong Kong for a weekend, they decided to call up Imelda Marcos, whom they’d met in New York, and visit her in the Philippines, and while they were there they stopped by the mountain set where Francis Ford Coppola was filming ‘Apocalypse Now.’ ”

Oh, that’s true. When you read it, it sounds so ridiculous. I’m so embarrassed! I was in Hong Kong for work. It was the beginning of our relationship. He comes and visits me. After two days in Hong Kong, what do we do for the weekend? Look at the map and see that the Philippines is not so far. I had met Mrs. Marcos, because Warhol called me one day and said, “I would like you to come to Trader Vic’s to have dinner with Mrs. Marcos.” He had also invited Lee Radziwill. He said to Mrs. Marcos, “I’m going to invite these two princesses.” So we had dinner with Mrs. Marcos, and she goes, “You must come to the Philippines.” So I wanted to show off with Barry. I picked up the phone of the hotel and said, “I would like to speak to the First Lady of the Philippines.”

Later, I get a call from Mrs. [Gliceria Rustia] Tantoco, who owned department stores. She happened to be Mrs. Marcos’s friend, and also she had my dresses in her stores. She said, “Mrs. Marcos is not going to be there this weekend, because she’s going to see [Muammar] Qaddafi”—she was having problems with the Muslims in the Philippines. But she said, “You can stay in the guest house in the palace.” So we take the Qantas plane, and we do a visit, and I said, “Where are these ruins from?” Mrs. Tantoco said, “Oh, it’s part of a set! Francis Ford Coppola is shooting in the mountains.” Barry, who was at the time at Paramount, said, “Hey, let’s see Francis!” So they give us this helicopter, and we arrive in the middle of the Vietnam War.

What a weekend! I can see the commonalities. You and Imelda Marcos both have a certain extravagance. You’ve both been with very powerful men, except neither of your husbands have been dictators of any countries.

I only saw her once. I never saw her again.

[The chef brings out coffee and coconut ice cream on silver trays.]

How would you compare your two marriages?

Well, Barry’s different. But I’ll tell you one thing: they both love me. Egon really wanted children with me. The day I met Barry, he was very shy, very introverted, very mysterious. With me, it was an explosion. He just opened up completely and never closed.

But he was already the chairman of Paramount. How was someone who’s reached that height in Hollywood so closed off?

He was thirty-two. You’ll see. Next year you can read his book.

Are there things you learned about him from reading it?

No. We’ve known each other for forty-eight years. The first time he came out to the country, he was terrified to meet my children. On the way back, he had to stop at a red light, and we saw two old people crossing the street, holding onto each other. We both thought the same thing: one day it will be us. The only thing we disagree on is that he says it was Madison Avenue, and I know it was Lexington.

During the pandemic, your company went into free fall. You had to close all your stores in the U.S. except the one downstairs, and laid off a lot of staff. Was that something you could have avoided?

I had been losing money, because I had made a lot of mistakes. So it was an opportunity to take a pause. My distributor in China has fifty-nine stores, so they dealt with the factory, and I kept the design studio.

At the time, there were complaints from people who said that you hadn’t paid venders and hadn’t given severance to staff.

I paid everything. Sometimes it took a little while, but I took care of everybody.

A Times article from 2020 said, “Her glamorous personal brand had masked the fact that her fashion line had been losing money for years.” Do you feel that your personal story, which people can now see in this film, masked something that wasn’t working?

No, no. Listen, I wrote a book called “Own It.” I have never hidden. So many small fashion businesses were having difficulty. You own your vulnerabilities, and they become your strength. If you make people aware of your vulnerabilities, it adds to who you are. It doesn’t take away.

What’s the state of the company now? Is it profitable?

Yes, now it’s profitable, because I only have a design studio. But it’s very small. And I am at a crossroads. Between yesterday and today I’ve changed things, working to get more control of the design. But it is profitable.

You’ve talked about your dream to hand down the company to your granddaughter Talita. Have you had opportunities to sell it that you’ve turned down?

It’s all about what you’re leaving behind. I like to leave things nicely. I created a brand, and it lasted for a long time. I would like to put it in the best hands I can. There’s an iconic dress. There’s a huge archive. I could have sold my archives and my name for a lot of money. I wouldn’t want to do that.

I want to ask you about your personal taste in style. When you walk around the meatpacking district, seeing young people walking around looking their finest, are there things that you like or dislike?

I like people to be themselves. My contribution is giving women a little zing zing zing, so they feel just right and it’s their best friend in the closet. For me, it’s all about the fabric first. Then you color it, you print it. The silhouette has to be flattering. There are three types of women: women who like to show their waist, women who like to be loose, and women who like to be very tight, like a sausage. At my age, I want to be able to give all my sweet wisdom for women to be the women they want to be.

People say that we’re living in a prudish age. Do you find that to be true?

True. Much more than in my time. Me, I was at the peak of openness. There was nudity on Broadway! There was “Oh! Calcutta!” There was “Hair.” You would go to a museum, and there were happenings.

Do you feel like something’s been lost?

I don’t judge. I don’t like mediocrity, but I don’t judge. I don’t like shame, judge, be angry. All of this, it’s toxic.

One thing I learned from the documentary is how driven you are by the idea of freedom.

Freedom is everything. Freedom is everything. The first freedom, I guess, is your health. Then freedom to think, to express yourself. Financial freedom. If you are true to yourself, you are free.

Is there a kind of freedom that you’re still trying to attain?

No. I’m true to myself. I mean, sometimes I feel insecure. Sometimes I feel like a fucking loser, and I say, “I’m a loser!” But only losers don’t feel like losers.

Thank you so much for talking to me, Diane. [I get up to leave. Behind me is a huge mandala on the wall.] Where is this from?

You know, it’s not like I want to show off, but the King of Bhutan gave it to me. I said, “I’m never going to use it.” And look at it now. Isn’t it beautiful?

[She buzzes an assistant and asks for a copy of her autobiography, which she inscribes for me with the phrase “Love is life.” Walking home, I get a text from her with the photo she took of me, sitting in front of the mandala from the King of Bhutan: “A lovely lunch! See you soon. Diane ❤️.”] ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com