Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

“When I was ten years old, I looked up the word ‘homosexual’ in the family dictionary,” Robert Giard writes in the introduction to his book “Particular Voices.” “Symbolic act: I’ve been a gay reader ever since.” Giard grew up to become both a voracious reader (with a B.A. in English and American literature from Yale and an M.A. in comparative literature from Boston University) and a foremost chronicler of writers. His book, published in 1997, collects portraits he made of more than six hundred L.G.B.T.Q. authors. Giard’s archival impulse has been compared to such singularly focussed photographic compilers as August Sander and Mike Disfarmer, but, in a eulogy written after Giard’s untimely death, in 2002, at the age of sixty-two, the novelist Allan Gurganus aptly dubbed him “Our Nadar”: “Just as the great Nadar gathered the faces of each nineteenth-century artist or actor we might ever hope to see, Giard preserved the legs, tattoos, and laugh lines of Gay Lib Lit for future centuries.”

Cheryl Clarke and Jewelle Gomez, 1987.

Mariana Romo-Carmona and June Chang, 1988.

Giard grew up in a working-class family in Hartford, Connecticut. When he entered public high school, he was shunted onto the remedial track, because, as he wrote, “it was simply assumed that most kids coming out of my neighborhood, the boys in particular, were not ‘college material.’ ” He was saved, in his telling, by an older boy, a senior, who introduced him to literature, theatre, and opera. (Years later, he discovered that, like him, the friend was gay.) Giard began his career teaching middle school in Harlem and, through a friend, he met Jonathan Silin, a teacher at another nearby progressive school, who would become his life partner. They moved from the city to Amagansett, where Giard first began to pursue photography in earnest, working with a square-format Rollicord camera, and printing in a small darkroom that he set up in his new home. Some of the earliest pictures he made were self-portraits, often in the nude. When I reached Silin, via video chat, in the same Amagansett home that he had shared with Giard, he told me that with these works Giard was “exploring the idea of how it was to be a gay photographer . . . and understanding what it meant to be an artist living on the edge.”

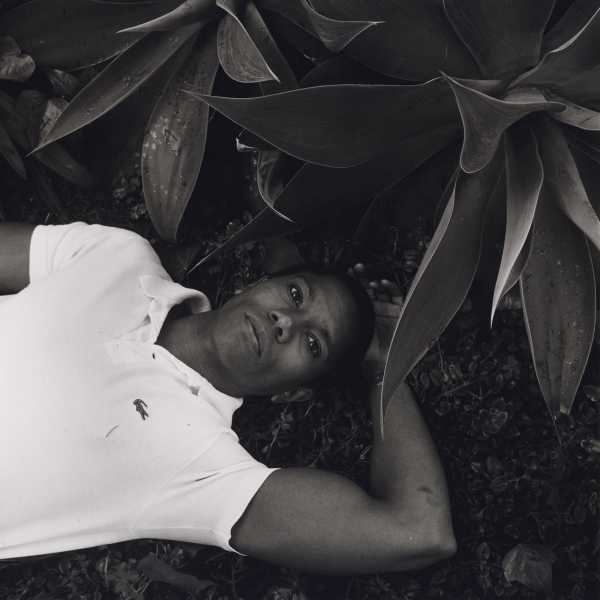

Larry Duplechan, 1988.

Alison Bechdel, 1995.

Edmund White, 1985.

Giard further explored portraiture, photographing friends, taking tasteful nudes, and, during the off-season, he created austere, desolate pictures of his corner of the Hamptons, in a manner that recalled the lonely cityscapes of Eugène Atget. But it wasn’t until 1985, some ten years after he first seriously picked up a camera, that Giard conceived of the project that he would doggedly pursue for the rest of his life. That June, after he and Silin marched in New York’s annual Pride Parade, the couple attended a performance of Larry Kramer’s play “The Normal Heart,” a semi-autobiographical work about an AIDS activist struggling to draw attention to the plague ripping through his community. “As I sat watching the play unfold in the darkened space of the arena-style theater,” Giard wrote, “its walls inscribed with the names of the dead, some of which I recognized, I was moved to a sense of urgency.” He went on, “By the end of the evening, I had arrived at a decision about my work: that it should be of use to gay people by recording something of note about our experience, our history, and our culture.”

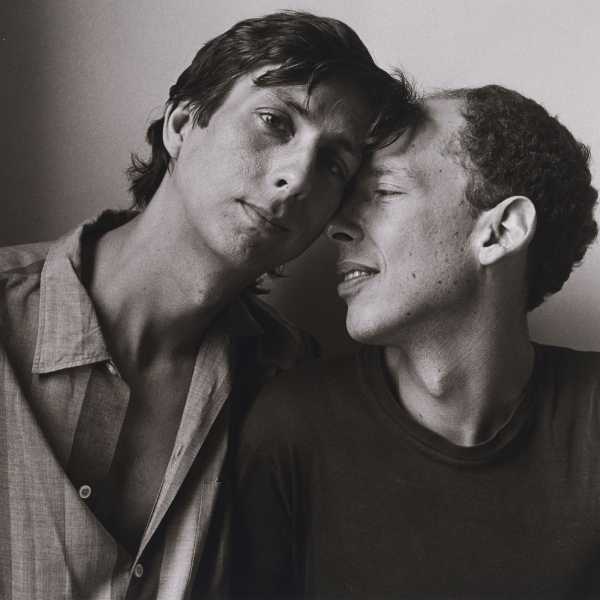

Michael Callen and Richard Dworkin, 1987.

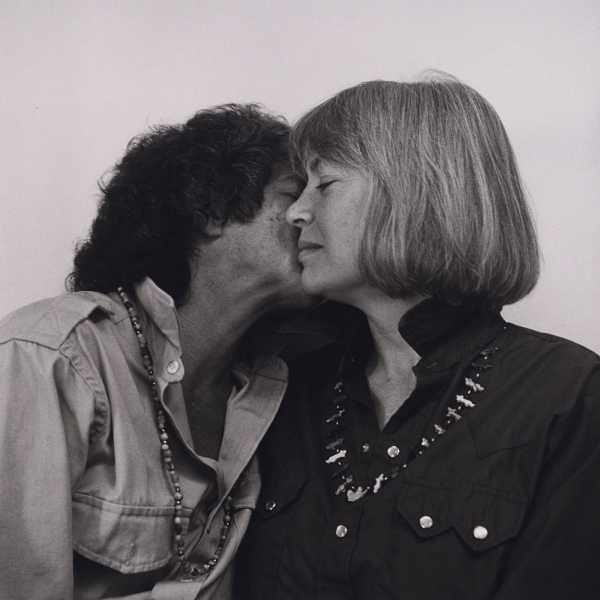

Blanche Wiesen Cook and Clare Coss, 1987.

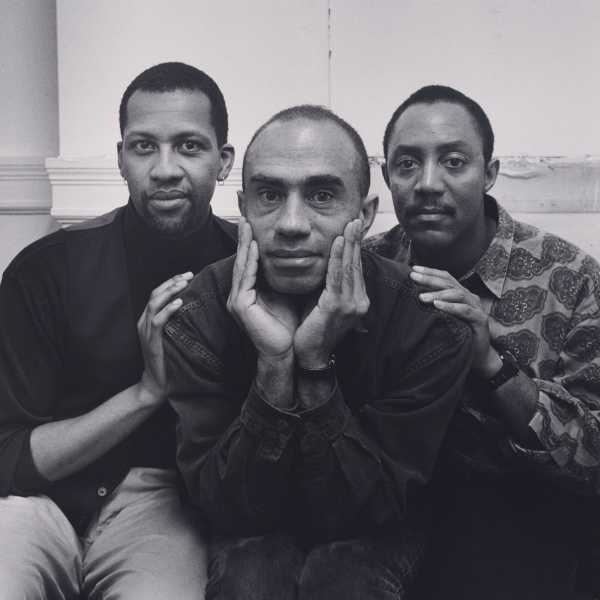

Not long after, Giard reached out to both Kramer and William Hoffman, another playwright addressing the AIDS crisis, and asked to make their portraits. That August, Hoffman sat for Giard and inaugurated the project. A few years later, Giard photographed Kramer looking plaintively out a window, wearing a sweatshirt printed with the famous activist slogan “Silence = Death” and festooned with a button made by ACT UP; his dog, Molly, sat cradled in his lap. Over the ensuing decades, Giard photographed writers working across many genres—playwrights, poets, novelists, theorists, memoirists, critics, even cookbook authors. (Remarkably, Giard made a point of reading some or all of the work of every writer he photographed.) Fame was in no way a prerequisite, though he did photograph contemporary luminaries and lightning rods, among them Allen Ginsberg, whom he captured holding his own portrait of William S. Burroughs; Edmund White, the great memorist who died this month, posing in a shirt and tie and sporting a trim mustache; a serene and queenly Audre Lorde; Andrea Dworkin, next to the smudgy blur of her cat; and Tony Kushner, lounging on his couch with a pair of pillows featuring the face of Karl Marx. Some young writers he captured, such as Sapphire, Wayne Koestenbaum, and Alison Bechdel, went on to become cult figures. Others have been largely lost to history, such as the members of the Pomo Afro Homos, a San Francisco-based Black theatre troupe; Foster Gunnison, Jr., an L.G.B.T.Q. history archivist, railroad memorabilia enthusiast, and smokers’-rights advocate; and Tobias Schneebaum, an erstwhile Abstract Expressionist painter turned memoirist who vanished into the Peruvian Amazon to live with the Harakmbut tribe and reëmerged with a story about eating a chunk of human heart.

Gloria Anzaldúa, 1988.

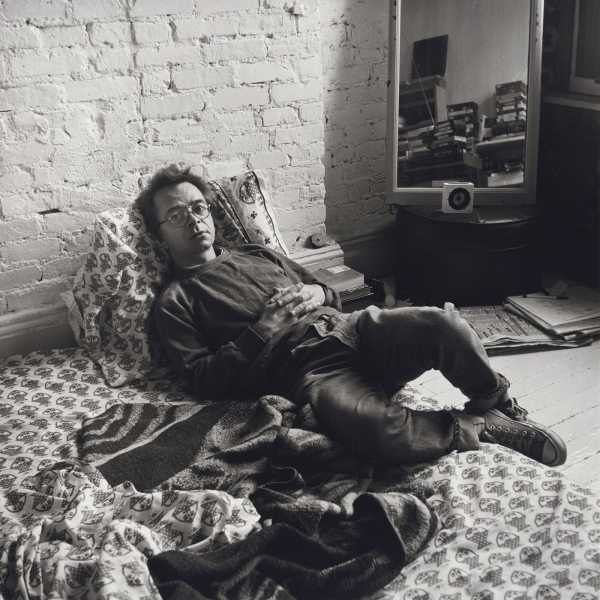

Gary Indiana, 1989.

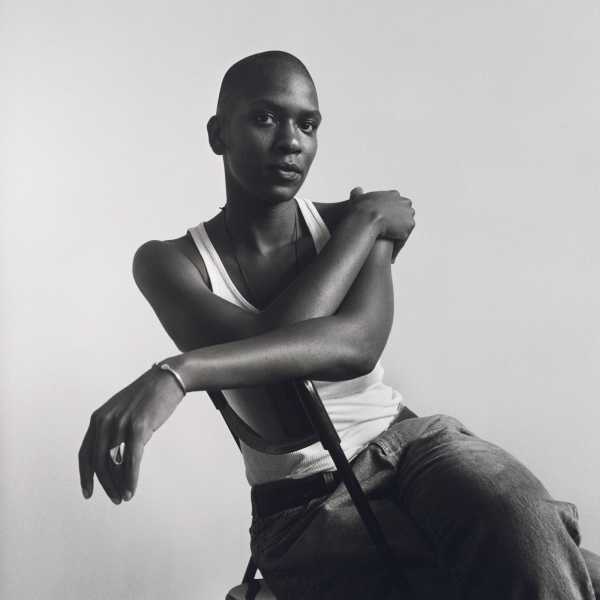

Pamela Sneed, 1992.

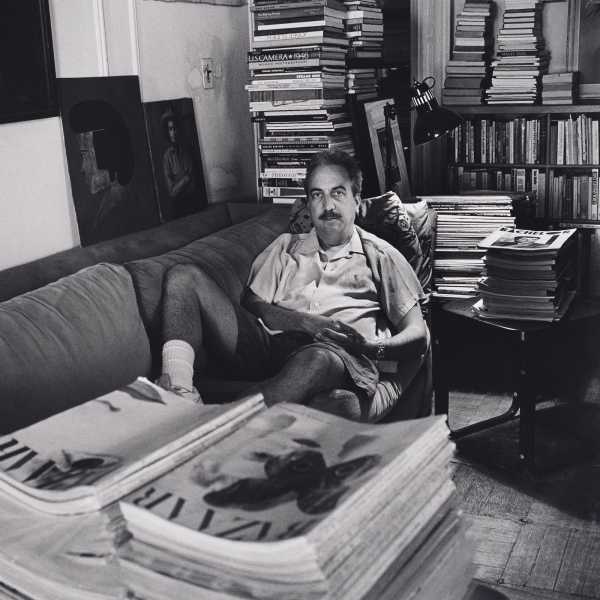

Vince Aletti, 1993.

A few of the pictures in “Particular Voices” have a kind of perfunctory quality, as if Giard were trying to cross as many writers off his list as time allowed. But the vast majority transcend the simple task of archiving. You can imagine, for instance, his elegant image of the poet Essex Hemphill, or one of the artist and poet Charles Henri Ford seemingly lost in thought, or his intimate depiction of a lounging Gary Indiana, hanging in the company of work by more famous contemporaries such as Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Hujar. Many of the writers Giard photographed chose to use his pictures as their official author portraits, and many praised him for his ability to capture their essence. The novelist Matthew Stadler, who had once been photographed by the legendary author photographer Marion Ettlinger, said approvingly that she had made him look like “a kind of younger brother to Charlie Sheen.” Nevertheless, it was Giard’s picture of him—rumpled, half-stunned, hunched in a chair in a corner of his Seattle apartment strewn with books, papers, and jumbled sneakers—that he declared to be “the best photograph ever taken of me, the most accurate record.”

Assotto Saint, 1986.

Jacqueline Woodson, 1992.

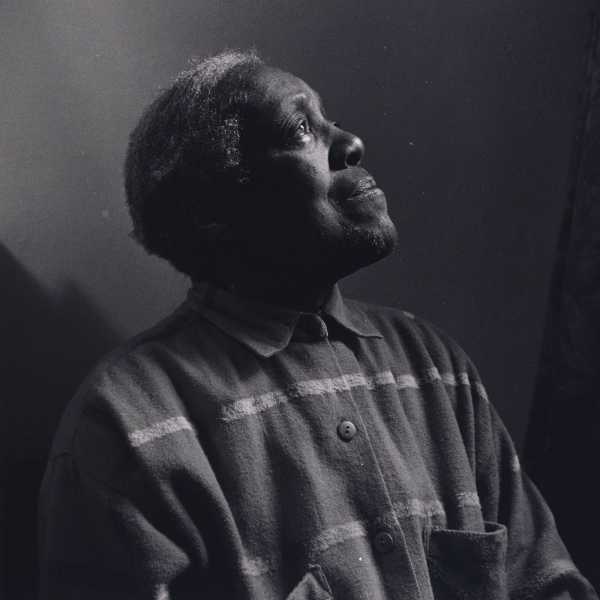

Mabel Hampton, 1989.

One of Giard’s most endearing quirks was that, despite his peripatetic practice, he never learned to drive. In his writing, Giard chalked this up to “reasons that probably mingle in equal parts history, chance, economy, aesthetics, and pathology.” Silin told me that Giard “had a commitment to public life, public transit. He railed against the way that cities were being destroyed by highways that crisscrossed around downtowns.” It was sadly fitting, then, that Giard died on a public bus, on his way to a shoot in Chicago. The cause, Silin speculated, was a congenital defect in his carotid artery, a condition which ran in Giard’s family. With cruel irony, given how Giard had spent his life campaigning for the visibility of L.G.B.T.Q. people, Illinois state authorities wouldn’t release Giard’s remains to Silin, since their partnership was not legally recognized.

Pomo Afro Homos (left to right) : Bernard Djola Branner, Brian Freeman, and Eric Gupton, 1994.

There is a sense in which Giard’s photographs were always about death. They were born out of a pitiless epidemic, as a poignant yet futile attempt to allow his subjects to live forever on film. “Photography,” Giard acknowledged, “is par excellence a medium expressive of our mortality, holding up, as it does, one time for the contemplation of another time.” But the pictures are also about what can endure, and inspire. “It is my wish that tomorrow,” he wrote, “when a viewer looks into the eyes of the subjects of these pictures, he or she will say in a spirit of wonder, ‘These people were here; like me they lived and breathed.’ ”

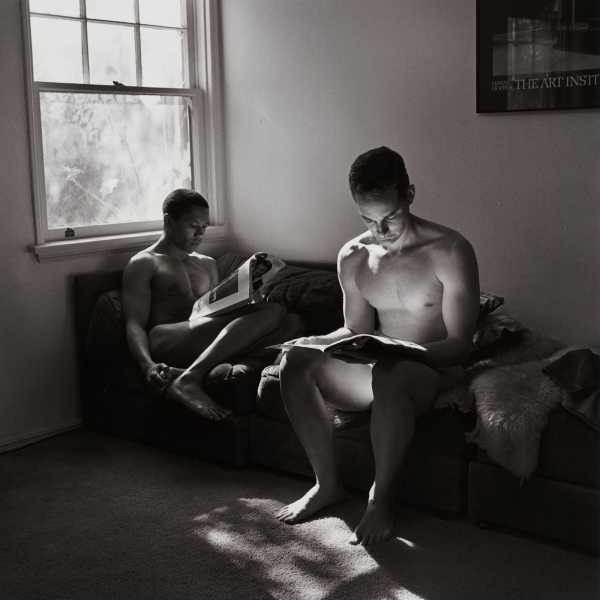

“Sunday Morning”: Larry Duplechan and Greg Harvey, 1989.

Sourse: newyorker.com