Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

John Updike’s professional relationship with The New Yorker began in 1954, when he was twenty-two and the magazine published his poem “Duet, with Muffled Brake Drums,” but his personal fascination began much earlier: he started submitting poems, drawings, newsbreaks, and other creative work to various magazines, including The New Yorker, at the age of thirteen. In his lifetime, Updike published more than a hundred and fifty poems and more than a hundred and sixty short stories in the magazine. In addition to working for the Talk of the Town section for two years in the mid-fifties, he contributed about three hundred and sixty book reviews. (The New Yorker was a family obsession: John’s mother, Linda Hoyer Updike, also published ten stories in the magazine, and his son David contributed six.) Updike’s final submission to The New Yorker was the poem “Endpoint,” which came out a few weeks after he died, of lung cancer, on January 27, 2009, at the age of seventy-six. These letters to and about The New Yorker are addressed to, among others, Updike’s family, in Plowville, Pennsylvania, a farming community near Reading; Mary Pennington, who was an undergraduate at Radcliffe when Updike was at Harvard, and whom he married in 1953; and the New Yorker editors Katharine White (whose husband was the writer E. B. White), William Maxwell, and David Remnick. The letters have, in most cases, been abridged. They will appear in full in “Selected Letters of John Updike,” edited by James Schiff, in October.

To The Editors of The New Yorker

Plowville, PA

March 21, 1949

Gentlemen:

I would like some information on those little filler drawings you publish, and, I presume, buy. What size should they be? Mounted or not? Are there any preferences as to subject matter, weight of cardboard, and technique?

I will appreciate any information you give me, for I would like to try my hand at it.

Sincerely,

John Updike

To Lilly March, columnist for the Reading Eagle, Reading, Pennsylvania

Plowville, PA

August 10 or 11, 1951

In her column of August 10, 1951, March had accused her “once-favorite magazine” of following a “party line,” injecting politics into its pages, and growing dull to the point that she was about to cancel her subscription. In her August 13th column, she printed this letter from Updike, prefacing it with: “We are honored to have on our summertime staff a Harvard undergraduate, one John H. Updike, who is majoring in literature, which he regards as highly impractical but fun. That it may turn out to be practical as well is nicely illustrated in a letter he wrote to me taking me to task for my stand on a well-known periodical, publishing under this heading last Friday. Mr. Updike, who flattered me greatly by stating that I was alive and THINKING in 1925, says”:

My Dear Miss March:

In a recent column you explain why you are dropping your subscription to a certain magazine. For reasons of policy, I presume, you neglect to name this unfortunate publication—I shall be equally coy. Even though you refer to it as a “little leopard” (hinting at a jungle-like quality) I have inferred that you speak of a metropolitan weekly with a modest but arrogant circulation. If this inference is incorrect, then you need read no further. You might have meant a ladies’ magazine which has a party line as rigid and sterile as that of, say, either the Communist or Prohibitionist parties; if that is the case, let me congratulate you upon this action and I can’t understand why you bought the thing in the first place.

If it is the one I have in mind, however, I think you are making a mistake. You were one of those people fortunate enough to be alive and thinking in 1925, when Eustace Tilley discreetly showed his face upon the newsstands for the first time. And I cannot help but think that part of your action is prompted by the gray might of nostalgia. You long for the good old days, that first golden decade when Soglow’s little king had not been demoted to the comic strips and Arno’s humor was not diluted by good taste; when E. B. White turned out “Talk of the Town” single-handed and Rea Irvin did every other cover; when Dorothy Parker lamented her love life and Alexander Woollcott spat upon the world in a prissy furor; when the Algonquin was more than a memory and Harold Ross entered the office one day to find a telephone booth overturned and in it James Thurber, a large lily in his hand. Many of the golden names—Woollcott, Parker, Robert Benchley, Ralph Barton—are gone now; many, tarnished—White writes scarcely anything any more. Thurber himself is getting nostalgic. And you are unhappy because a gay adolescence has passed. Genius is gone, leaving only talent. You have witnessed (heaven forbid this phrase) the passing of an era.

Is this so? Certainly the magazine is showing its age. Maturing is a mixed blessing, but failing to mature is an undiluted curse. Eustace Tilley is gray now about the temples, his walk is less buoyant, he pants slightly as he climbs the steep staircase to the humor he attained once without apparent straining. But he is not as ancient as you would have it; he is still wearing a contemplative sneer. Read for “violent impartiality” Wolcott Gibbs attacking a bad musical, John McCarten disdainfully brushing aside a mediocre film, or, specifically, Alfred Kazin’s panning of the over-touted treatise Worlds in Collision. And impressive indeed was the recent, snarling crusade against the blaring commercials in Grand Central.

You tell the reader of the guilt complex that led you to sacrifice eight out of 11 magazine subscriptions to aid the war effort. Was it not this same feeling that led this magazine to devote an entire issue to Hersey’s Hiroshima, that led a so-called “adult comic book” (a railroad official so called it) into some of the best reporting of the last World War? Is this not the “sense of mission” that, even though you share it, you condemn in a publication that, like yourself, is vaguely troubled? This spirit, this anxiety has forced the irresponsible magazine that once announced it was not for the old lady from Dubuque into formulating a party line, and hewing to it.

I am not sure what you mean by party line. You talk as though it permeated the publication cover to cover, but can it affect the short stories, the cartoons, the columns on tennis and horse racing, the Parisian letter from Genêt, the poetry of Morris Bishop and Phyllis McGinley? Does this party line assert itself in a political essay by Richard Rovere or a thoughtful paragraph in “Talk of the Town”? Does it make one bit less funny a Charles Addams study of the grotesque, an iota less powerful an O’Hara fragment of modern America, a smidgeon less wistful a Thurber dip into the Columbus of his childhood?

Your “party line” can mean but one thing: an occasional tendency to take things with seriousness. Not a function of a humor magazine, perhaps, but this one has long ago ceased to be just that. It is above all a timely magazine; and now is not the time for continuous laughter. It has recognized that this is not 1925 but a time when the nation is as sensitive and as jumpy as an exposed nerve. It is to the credit of a magazine when it recognizes the necessity for anxiety.

You speak of dullness. Dullness is a relative quality. I, for example, found the poet Lucretius quite dull, not because he was, but because I thought he must be. Study of Latin was a repugnant idea. Perhaps equally repugnant is the thought that a magazine that once thumbed its nose seems to have shifted its hand and sadly scratches an ear. But however tired it makes us feel, we must acknowledge the integrity of the magazine that has allowed itself to express a very unurbane, unsophisticated, even unfunny sense of mission. I do hope that you and the weekly will not part company. You never needed each other more.

With lamentable haste,

The Office Boy

To Mary Pennington

Plowville, PA

June 28, 1952

Dear Moparopy:

I am now heading into the eighth hour of my nice shiny seventeen-hour day at the Reading (Pa.) Eagle. Last night I got in at two o’clock, found my parents up in their nightclothes on the verge of starting walking into town to retrieve me from the gutter they fondly imagined I had been left in. . . . I went into Shillington [the Pennsylvania town where Updike lived until age thirteen and attended high school] under the impression that I would make some progress with the impending class reunion, and instead became involved in a beer brawl and charade-fest that lasted into the monodigital hours. . . . I succeeded in infuriating one waitress at the Shillington Diner. Method: tossing lumps of sugar in all directions, spilling coffee on things, shouting, and finally making an elaborate apology for what I termed “the ill-advised conduct of my friends.” My head has been bumping softly all day. . . .

The ice with the old New Yorker has been broken: they snappily returned my first story of the summer with a strangely reassuring rejection slip. I always feel happier when I’ve received one, for some damn perverse reason. A rejection slip represents a response, an acknowledgement, and a sort of accomplishment in itself. I love them. It also means that I still have a good way to go, but never reflects on my lack of ability to make it eventually. It should, surely. I am on the verge of being overdue. I am conscious of something lacking in me; a tenseness that refuses to admit any kind of general vision that makes a poor bedfellow with my refusal to submit entirely to the view of creation as a craft. However, there are a few things I am groping for. None is as dangerous as a too keen awareness of critical response. I think that this age is one in which criticism has outdistanced creation; artists are desperate in their attempts to equal the subtlety of modern critics; the quality of a piece of writing is judged by the number of academic statements that can be made about it. This is not merely a creative “sterility” we hear so much about. The term “sterility” tends to make art a bitch in heat. It is not. In fact, it is not anything. Everyone has a right to define the artist in special terms, and to attempt an epigram that will make a reality out of a convenient term. But the fundamental notion to be grasped is one of purpose. And every human contrivance is oriented toward an increase of human comfort. And only until I really believe that writing is a phenomenon of humanist activity that derives reality and dignity not from any personal concepts of nature or abstract notions of function but from its simple-minded purpose: diversion, only when I have recognized all else—primarily, the notion that it is self-expression—as either fallacy or ornamentation, can I hope to be professional. And this sort of realization is one that requires a weary mind and a realism seldom found in the young.

Dear me, I certainly do get heavy when I confront a sheet of paper that will eventually find its way into your hands. Well, that’s the way it goes. . . .

Johnny

To Mary Pennington

Plowville, PA

July 1952

’Allo keed:

How is tricks? But this is an inane question, inanely phrased, because your letters so admirably inform me of your version of tricks. You write a v. neat letter, my lovely, and I turn my freckled face to Heaven in thanks every time I receive one.

Thus the mails both sustain and batter me, for The New Yorker has a rejection slip for every missive you can send. I just am recuperating from the rejection of two little lyrics that I foolishly thought they might like. Time was, chick, when I used to absorb a rejection slip or two every day of the summer, and wax mighty on them. But I’m not getting younger, and my resilience is stiffening. It takes a lot out of one’s confidence and a bit of peculiar courage to trot obediently upstairs, a reject clutched in your hand, and start work on something else that you know in your heart won’t be any better than the thing rejected. Everyone is quick to point out the absurdity of my expecting something better at my tender age. True, I am only twenty, and forty is the usual estimate for a writer discovering competence. But I have never conditioned myself for failure, and am not characterized by any great patience. I shall shortly have a wife to support, and a destiny to confront. And here I am, puttering around with postage stamps. True, I am twenty, but I have, since I was sixteen, received about three hundred rejection slips, at least a hundred from The New Yorker, and I’m getting tired of them. How long, O Lord, how long! I’m awfully sorry about this whining, but you must know things like this, for you, if you still can stick with it, have not taken an easy way out or pounced upon a quick meal ticket. I see this now, and I am sorry. I would like to be a genius, for your sake, but the only thing of truly monumental character about me is my capacity for absorbing praise. The rest is drudgery and endurance. You come along at your own risk. . . .

Johnny

To Plowville

Sandy Island, NH

July 27, 1953

Dear Plowvillians:

. . . A very pleasant thing happened the other day, the 23rd, when a poem of mine came back from The New Yorker with this letter:

Dear Mr. Updike:

“The Lovelorn Astronomer” isn’t right for The New Yorker, but there were many things about it that we liked, and we hope you will continue to let us see your Work.

Sincerely yours,

William Maxwell ← forgery

William Maxwell.

Q: Who is William Maxwell? At any rate, it was the best thing that has happened to me for some time (since I married Mary) and the thrill of it was slightly dulled by the arrival of another letter that same day, with another poem (17-yr locust):

I am sorry but this is again not right for us. Nora Sayre tells me that you sometimes write light verse as well as serious verse. We are always anxious to have it in the magazine, and, as I’m sure I don’t need to point out, there is very little true light verse being written now—not that there ever was too much of it.

Wm. Maxwell

Nora Sayre is a girl I knew slightly at Harvard, who went around with Steele Commager, the son of the historian. She is the daughter of Joel Sayre [a novelist, a reporter, and a screenwriter], which I presume is how she got an in with this New Yorker man. At any rate, at least one of them knows my name now, and a chink seems to have opened up in the long blank wall I have been looking at (via the mails) for nigh onto five years. . . .

Johnny

Telegram to W. R. Updike, father

Montpelier, VT

July 15, 1954

New Yorker buying Rolls Royce poem [“Duet, With Muffled Brake Drums”] future things must go to Mrs. White Whopee—LOVE

John

To Plowville

Star Island, NH

July 18, 1954

Dear Plowvillians:

. . . The check from The NYer hasn’t come yet, so there is no more information on the long-awaited acceptance. If I had either the poem or the letter (from Robert Henderson [an editor at The New Yorker], whoever that is) I’d send you copies. The poem began, “Where gray walks slope through shadows shaped like lace / Down to dimpleproof ponds, a precious place / Where birds of porcelain sing as with one voice / Two gold and velvet notes: there Rolls met Royce.” And so on. Mary doesn’t like it as well as some of my other things, and my own hopes for it weren’t abnormal, but I can see now that I almost by accident achieved a happy merger of polish and incongruity, and blended the clarity of my light stuff with the glitter of my “serious” poetry. A merger I hope I can bring off again. I am writing poems a mile a minute—my vacation has finally limbered up the old creative itch—but I keep pecking away at prose things. Prose, I figure, is going to have to be my bread and butter, even if right now my poetry is a little better developed.

All in all, the last two months have been so replete with blessings that I feel somewhere an ax is going to fall. Of nights I have been thinking about death and eternity and scaring myself crazy, like I used to do when much smaller. Idleness seems to breed awareness of one’s own transience. . . .

Johnny

To Plowville

Moretown, VT

July 25, 1954

Dear Mama, Daddy, Grammy:

. . . The letters from The New Yorker continue to stream in; evidently, once you make a dent in their hides, they are just too gushy for words. Following on Mr. Henderson’s note signalling acceptance came a $55 check, with a lengthy letter from Mrs. White saying how delighted she was I had sold something, how she had read the Lampoons and hoped I would become a contributor, how if I wrote any prose I should send that along, how I should “bombard” them with verses, etc. Next, Mr. Henderson sending a proof of the poem, as it will appear in print, with several stupid corrections of my punctuation and a ghastly, unmetric word substitution by Mrs. White. I changed her change, distinctly explaining why hers was unbearable, changed the punctuation back to my way, and sent the proof back. [In margin: I don’t know why I sound so nasty about it. Mrs. W. is really very sweet.] And now, just yesterday (Saturday) a letter from Mrs. White saying how sorry everybody was that they didn’t use a dinky poem of mine called “Solitaire.” It’s so heady, in fact, that I’ve stopped writing poetry all together and switched to prose. $55 is all very well, but scarcely grounds for support. Still, it’s delightful, and it might appear at the end of this week. . . .

Johnny

To Katharine White

Plowville, PA

September 2, 1954

Dear Mrs. White:

Thank you so much for your kind words about “Friends from Philadelphia” [Updike’s first short story accepted by The New Yorker]. . . . I once saw a movie in which a chimpanzee, let loose in a laboratory, proceeded to mix, by accident, with his elbows, some sort of highly potent elixir. I know now how he felt when they wanted him to stir up a second batch. The bonus-for-quantity plan, though, sets a properly optimistic tone, and I am grateful to you for sending it to me. . . .

I go to England the day after tomorrow. Brooding about the venture has produced the enclosed poem. I am afraid you won’t be at the New Yorker office when I call tomorrow, so this is the time to tell you (a) my middle initial is not “F,” but “H” (b) the patient and abundant attention you have paid to my offerings this summer is one of the nicest things that has happened to me in my brief and lucky life.

Sincerely,

John Updike

To Plowville

213 Iffley Road, Oxford

September 20, 1954

Dear Plowvillians,

This morning, our first delivery of mail, and a pretty batch of letters it was, too. A contract and $100 check from The New Yorker, and a cheerful, if slightly miffed-sounding letter from Plowville. I gather none of my letters had reached land by the 14th of September. I am awfully sorry. If we could do it over again, we certainly would have cabled—our failure to do so has cost everybody, it seems, much more than a few dollars worth of worry. But by now, I trust, anxiety in the United States has been relieved. . . . Tell Grammy that on this side of the Atlantic there is nothing to mumble about. We are well, although Mary is having a terrible time locating an obstetrician. This morning we went to a Maternity Hospital, but the atmosphere of the place didn’t really seem hallowed enough for the mystery of birth. . . . And Mary can’t get up nerve to buy meat. The market is just full of butcher shops, with the most ghastly whole pigs and halves of steers hanging from horrible hooks. Much blood, and one poor Porky had been cut down the middle as neatly as an anatomy drawing in the medical textbook. It takes a strong stomach to shop in England, and we tender Americans must be eased into it by way of canned sausages. . . .

The letter from The New Yorker also has a miffed undertone: Mrs. White starts out “I have been waiting a few days hoping we should receive your address in England before sending you . . .” So virtually everyone thinks England is closer than it is. But she warms to her task, going on to explain that they want me to sign a “first-reading agreement,” which, in return for my promise to send them all poems and stories first, they will tack 25% onto the buying price of any they buy. But that’s not all. “In addition we hope—and expect—to pay you a quarterly cost of living adjustment (called familiarly, in our office jargon, “COLA”) on everything we buy. . . . At the moment COLA adds well over 30%.” After some more office jargon, to say coyly, “It is rather unusual for us to offer an agreement to a contributor of such short standing as you, but you have produced so much this summer and so much of it seems to be right for us that we did not think it fair to wait longer to offer you one.” This does not obligate me to contribute, it just means they see whatever I do first. . . . And finally, “The one hundred dollar check enclosed is a symbol of our good faith; one goes along with every agreement, to bind the bargain.” That’s the kind of symbolism no literary man can get too much of. . . .

Johnny

To Katharine White

213 Iffley Road, Oxford

September 30, 1954

Dear Mrs. White:

I am very sorry that I haven’t got this proof back to you sooner. It came to me less than an hour ago. It was stamped with six cents, obviously under the impression it was bound for somewhere in the States. So it went surface mail, and even when it arrived in Oxford (on the 29th, the postmarks say), it hung around a while in General Delivery, probably hoping for me to show up and pay the tuppence due on it. The poor envelope is riddled with official-looking markings. As Max Beerbohm says, “There is always a slight shock in seeing an envelope of one’s own after it has gone through the post. It looks as if it had gone through so much.”

Yes, I do own a copy of Fowler, but along with my parents, pet cat, rubber basketball, and other steadying influences, I left it in America. Colons tend to be a weakness with me ever since I took a course in the works of George Bernard Shaw. They look so pert and snappy, somehow. I always think of a semi-colon as dragging one foot. I fear in poetry I use punctuation improperly, to indicate the degree of “stop” I want. Thank you for correcting me.

My selling you something very timely from England is a pleasing notion, and of course if it should happen, you have my permission to do minor editing without consulting me. I hope our concepts of “minor” editing correspond. I should think that in a poem, the change of any word would be major. In prose, I’ll trust you to draw the line between merely syntactical and fundamental alteration. Air mail from New York City to me takes two or three days, only slightly longer than the average time between NYC and Vermont or Pennsylvania. I appreciate that in any case The New Yorker is extraordinarily considerate of its authors, and I, for one, am grateful.

Sincerely,

John Updike

To William Maxwell

213 Iffley Road, Oxford

October 4, 1954

Dear Mr. Maxwell:

I’m pretty embarrassed. In a rather garrulous letter I wrote Mrs. White this morning, I suggested there would be some noise from me concerning the galley proof of my story [“Friends from Philadelphia”]. But I’ve just read the proof, and the only improvement I can suggest is that “Friends” be spelled correctly in the title. Otherwise, it read slick as a whistle. I’m sure it isn’t the way I wrote it, quite, but there was no pain at all, so it must be the way I had wanted to write it. I can scarcely wait until it appears. . . .

Sincerely,

John Updike

To Plowville

213 Iffley Road, Oxford

April 2, 1955

Dear Plowvillians:

I cannot begin to tell you what a charming person this Elizabeth Pennington Updike is. I had a glimpse of the child last night, but only for a moment. Evidently I was so impressed the nurse has been bothering Mary all day with what a cute papa I am. I dare say I am, else how could I have had such a cute baby? . . .

Meanwhile, the world plods on. The NYer has rejected some things of mine, all of which deserved to be, and in a very cordial way. Mrs. White calls me “Dear John” now and says, “I assure you that your desire for perfection is much appreciated. Far too few writers have it.” Cass Canfield, Chairman of the Board of Harper & Brothers, writes me, “Whatever you may write, we would be glad to have an opportunity of reading the material. But frankly, a book of short stories is usually a difficult kind of book with which to launch an author. A collection of your poems would be probably easier to sell. I am delighted to hear that you are still thinking in terms of writing a novel.”

Now I must stop. Have to get up early enough to go to church. “For all of us,” Mary says.

John new pen [in blue ink]

To Plowville

Liverpool

June 26, 1955

Dear Plowvillians:

. . . This caps a week of very pleasant . . . contact with New Yorker personalities. In the twenty-four hours between 4:30 Wednesday and the same time Thursday, I met Mr. and Mrs. Thurber and Mr. and Mrs. White. While all were as nice as they could be, it was Mr. White by a mile as far as personality honors go. Has there ever been a sweeter man? He is about Mary’s height, looks ten years younger than his 56 years (Thurber told me his age), and suggests a rabbit, who has been in many bars.

He and Mrs. W rolled up in an enormous hired car on Thursday at 1:30. I rushed out, my heart beating like a butterfly in a jar, and he was climbing out of the car, saying “Hi,” with a smile that suggested (a) how it was for him to meet me (b) isn’t it funny for us all to be in England this way? (c) isn’t this huge hired car ridiculous? Then while I was grappling with Mrs. White, he went into our apartment, said to Mary, “I like your digs” (Mary can’t emphasize enough how perfectly this put her at her ease), and charmed the baby sitter, a Ruskin School denizen name of Tom Englehart. At lunch, which I mismanaged from the start, he displayed an uncertainty and confusion fully equal to my own, and if Mary and Mrs. White hadn’t taken the menu from us no doubt we’d be sitting there yet. Actually he wasn’t quite as vague as I was; he was certain of one thing: that he wanted a drink. I can’t remember all the nice things he said, but among them were: (to me) “I certainly hope you aren’t thinking of giving up the literary game” (this after I had issued some protest about my growing ineptitude); “I never read The New Yorker” (after Mrs. White consulted him about some story we have been discussing); “I gave up sheep because when I have animals I can’t do anything but think about them.” He and Mary had a long discussion of their hay fevers, and Mr. White gave her half of a blue pill, which cured her hay fever for the afternoon. He told several stories, all of them involving some embarrassment or discomfiture he suffered. Ugly things are always happening to him in London, it seems, though they didn’t seem very ugly to me. One of them was that he got lost in trying to find Cook’s Travel Agency, and began to ask a doorman the way, when, looking up, he saw “Cook’s” written on the man’s hat. He felt this was pretty awful. A stranger would have some difficulty in associating this shabby, forlorn, murmuring figure with America’s leading essayist, and I am tempted to say that he seems quite untouched by his own greatness. But there is a certain repose in those pale-blue irises to show he is not unaware that he has made a good thing of what was given him, and I think it takes a high degree of inner security to be so unassuming.

One doesn’t quite know what to make of the Missus. . . . Mrs. W is short—shorter than E. B.—and darkish, with a sharp birdy nose. One of the more alert gypsy fortune tellers. I had difficulty coordinating her with the fairer, less wrinkled image I had built up from her handwriting, and if it hadn’t been for Mary—smiling, calm, lovely—I might have thrown away the ball game. As it was, I doubt if I said more foolish things than I ordinarily do over the same time-span. She pressed me about the job, and I, in trying to clarify my feelings, rather muddled the situation, and the whole thing got rather left up in the air when E. B. suddenly remembered something else grisly that happened to him. The thing isn’t if I want a job (I do) but what sort. Mrs. White, naturally, didn’t want to suggest I could have any job I wanted, and on the other hand tried to get across that there was a choice. Furthermore, being away from Mr. Shawn [William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker], she didn’t really know the score. But the choice, I should think, would be between writing of some sort and being a reader of unsolicited manuscripts. I believe I would enjoy editing—I had a wonderful time discussing published stories with her, and enjoyed the editing aspect of my Lampoon work—but I fear I might get caught up in editing, and become another one of those dreary New York people “in publishing.” If I had more character, I think going to work in a steel mill might be the thing. So going into the Army might be exactly right, and if I am not taken, relief and disappointment will be mightily intermingled.

The baby-sitter expressed a positive preference, as soon as they were gone, for Mr. In truth, there is something of a blunt instrument about Mrs. Even if her favorite author is Jane Austen.

Which leaves the Thurbers. On Wednesday, as I predicted in my last letter, Peter Judd drove me down to Nora Sayre’s London flat—garish and stylish, like a modern furniture ad—and eventually, at 4:30, the Thurbers showed up. Thurber is a half-inch shorter than Daddy, and his glasses bulge one eye way out like Grandpa’s spectacles did. I didn’t expect quite such a fatty and formless chin, and the voice—reedy, highish, and rather unexpressive—was a bit startling. A blind man is, I fear, a public man. It would be impudent to pity a man who has made so little of his handicap, and who bears it with such good humor and un-self-consciousness, but in truth it was touching to see those great shoes shuffle along the carpet, wary of the step or table lurking in the darkness, and even more so when, before he got us situated by our voices, he directed his smiles and remarks to an empty portion of the room. A blind man probably takes what friends he has into his cave with him, and I made little impression on him. Not that I expected to.

I was able, thanks to my knowledge of New Yorker lore, to keep the pump of his anecdotage primed, and didn’t stutter too much. My NYer knowledge had a rather disagreeable consequence in that many of the stories he told I had read before, in some article or other, and in fact nearly every story seemed to me very smooth with frequent telling, and I had the feeling of being at a sparsely attended matinee watching a fine but aging actor. I kept wishing we were a bigger, or drunker audience. The drink was tea, and I gulped enough to activate my kidneys horribly. Popping up twice in an hour to the bathroom is bad enough, but it was made worse by the possibility that Thurber, ignorant of anything but the unsettling swish of the door, would address some remark to me in my absence. He is writing a book about Ross, and was full of the man. It was fascinating, and I am sorry that my account is so sour. It wouldn’t be, if Mr. White hadn’t been such an angel. . . .

Love,

Johnny

To Plowville

153 West 13th Street, New York City

May 21, 1956

Dear Plowvillians:

The apartment is still unrented, Mr. Shawn has evidently stopped sending me assignments, and Mary, all the signs indicate, will have another baby in January. Elizabeth, as if sensing her impending new position in the family, is taking on more and more adult wiles. . . .

My novel [“Home”], commenced somewhat after Mary’s baby, with luck should be completed (first draft) somewhat sooner. I made several false starts but now am on one that should stick, and the only trouble is I don’t know the names of plants and flowers. My quota for the day, three pages per, seemed modest enough, but it takes me all day to do them, and I feel as if I’ve done ten. Still the project excites me the way those first NYer pieces did.

Another project is to think of some way of escaping from The NYer. Not so much the magazine as the city. Not quite right for me, as the rejection slips say. I’ve been soliciting job ideas from the people I see and thus far have received these ideas: working for the Central Intelligence Agency in Washington; learn to operate a Univac computing brain for IBM; being a “factor” (running a trading post) in the Hudson Bay area; being a butler; and running one of the locks on an obscure Canadian canal. My own idea is to be a postman. Suggestions? . . .

Johnny

To Plowville

153 West 13th Street, New York City

February 18, 1957

Dear Plowvillians:

Such an action-packed week I can’t believe I forgot to write you yesterday. Last Monday I went up on the train to Cambridge, Ann Karnovsky drove me out to Ipswich, and a tall, fur-coated, initially austere lady name of Madeline Post drove us around to look at apartments and houses. Only one apartment; huge, but richly furnished, and the nervous owner wanted $200 per month. Next, we looked at Little Violet, a 5-room house, with barn, carport, study, and 2 acres, for $150. We never got inside Little Violet, it being locked and the real estate agent lacking keys. I just looked into the windows. I couldn’t see much except the little room with white shelves and white marble floor that I envision as my study. The barn seemed very pleasant too. Then we looked at some houses to buy, all of them full of young pioneer women raising dozens of children in the midst of more litter and television sets than I ever saw. We are taking Little Violet; the lease should arrive soon, and we’ll move around April 1st. Seems scarcely credible.

The reality of it didn’t dawn until, after one day of his being inaccessible, I saw Mr. Shawn to tell him I was quitting. The hands tremble even now, thinking of it. He was sweet as a mint paddy about it, though, and said I could come back any time. Mrs. White took me out to lunch today, after writing that my quitting was a crashing blow to the magazine and to her, personally, and was full of fun. Right off the bat I met J. D. Salinger, who was having lunch in the Algonquin with Shawn, and then at meal’s end Mr. and Mrs. Thurber came in. Mr. T. said he was glad to see me; I forget what I said, nothing much I guess. . . .

On Thursday Maxwell came down to Charles’ restaurant and had lunch with Mary and me; he spoke mostly of his dreams, which are rather literary and explicit. Sample: G. S. Lobrano (the editor who died some months ago) came back and Maxwell was so embarrassed that he (Maxwell) had such a huge carpeted office, whereas Lobrano had none, his old office having been cut up into little offices, a quaint custom of The NYer. So Maxwell offered him his, and Lobrano declined, and later Maxwell visited him in the office they had found for him, and discovered that the ceiling was just inches higher than Lobrano’s head and the walls inches wider than his shoulder. “So you see,” Maxwell explained, “I had put him in a coffin.” Then he came back to the apartment (this was real, we’re out of the dream) and looked at the babies. He was exquisitely polite. Now that I’m leaving they all seem so polite. . . .

Johnny

To Alfred Kazin, literary critic, who had written a piece in Time magazine referring to various Broadway plays as “adultery by intellectuals” who are able to live in Westport, CT, and who can “afford the slightly Bohemian reconverted barn in which the artist for The New Yorker, that safe citizen of our times, works.”

Caldwell Building, Ipswich, MA.

June 13, 1960

Dear Mr. Kazin:

I notice in Time a reference by you to “the artist for The New Yorker, that safe citizen of our times.” I don’t know why this kind of thing, so regularly emitted by Leslie Fiedler, Maxwell Geismar, etc., invariably causes me pain, nor why I am driven in this case to the indiscretion of writing you. . . .

My own relation to the magazine has been one of a grateful reader and then of a grateful contributor. I honestly believe that the magazine prints the best of what it gets, and prints it with much less editorial interference than is imagined. That no attempt is made to get a New Yorker kind of story; that, in the minds of the editors, no such kind exists. And that I have never seen in print any kind of case made out for the corporate identity of New Yorker fiction; and that the clearest notions of such a corporate identity exist in the minds of those who read the magazine least.

Without denying that some stories are better than others, and that even the best are seldom as good as the best of Chekhov, I know of no magazine doing half so good a job, and I have met no persons in any phase of publishing half so grateful and happy when they get some thing they think is good. It seems to me sad, therefore, when critics respectable enough to get their faces in Time consider it safe—to use a word of your own—to smirk at the magazine in passing. If this is all it requires, being an “intellectual” is quite as easy as being a rebel; rather easier, really. Almost as easy, perhaps, as living in a barn and committing adultery. Tush.

Sincerely,

John Updike

To Katharine White

Caldwell Building, Ipswich, MA

September 12, 1960

Dear Mrs. White:

. . . I was delighted to hear from you, and have some hope of bringing Mary to New York in the next two weeks, when you may still be there. We would both love to have a glimpse of you again; it seems several years since the last.

As to “Maples in a Spruce Forest,” though, I think the best thing is for The New Yorker to forget the poem. That is, I couldn’t be personally enthusiastic about making the changes, which would be quite difficult, since the poem is strung on a lot of off-rhymes that would have to be replaced somehow. The use of “doomed” for a noun doesn’t bother me; if you’re going to do this sort of thing, might as well do it twice in one poem, is the way I feel. The obscurity of

The life that plumps the oval

In the open meadow full

surprised me; it seems so clear to me. The oval is the oval shape of the maple that has been allowed to grow as it pleases in space. Maybe maples aren’t oval—but they’re probably more oval than round or square. Anyway, the lines mean something to me, and I would be at a loss to find an equivalent. Since the bank must be absolutely glutted with Updike poems anyway, I think the kindest thing I can do is not push this one. But I’m delighted that you liked it in the main.

Has The New Yorker changed its envelopes?—the ink seems blue now. While I’m sure that this move was contemplated with much caution, and is justified by many reasons, I must say that I thought the old black was much more classy. How my heart used to leap up at the sight of one of those envelopes, printed with such style and lack of fuss! It still does leap up, of course, but the blue muffles it a bit. So if you see the man who makes these decisions, you might tell him that one contributor and ardent New Yorker fan votes for black. . . .

Yrs.,

John

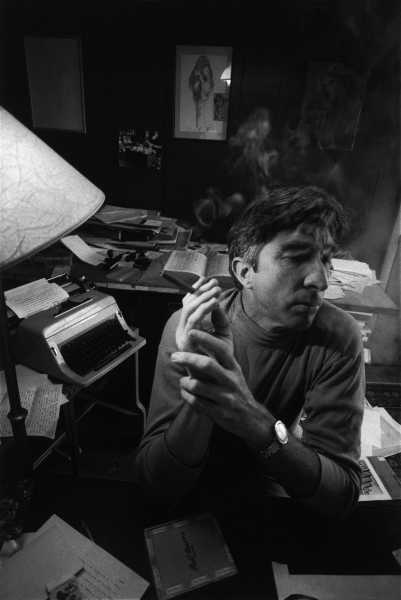

John Updike in his study at his home in Ipswich, in 1974.Photograph © Ara Güler / Ara Güler Museum / Magnum

To William Maxwell

58 West Main Street, Georgetown, MA

May 29, 1978

Dear Bill:

. . . What I am writing to tell you . . . is a curious piece of news that really of the outside world I can think of only you to share it with. David Updike—whom you may remember as that little male figure who tagged after us and our girls at a significant remove one day through the Metropolitan Museum of Art—just had a short story, at the tender age of 21, accepted by The New Yorker. He took it into his head to become a writer not more than a year ago, as far as I can tell, when he fell in with some girl who had literary aspirations. He seems to have lost the girl but kept the aspirations, and the story, which I read over at my old place yesterday, is a very tender five-page meditation on turning 21, his pet dog, and his old neighbor across the marshy river. . . . It’s a soul-stirring event that I imagined you might like to hear about.

Driving back from Ipswich today, where Martha [Updike’s second wife] and I gathered marsh hay for our possibly overmulched garden (I see the mulch; where are the plants?), I got to thinking about acceptances and rejections, and remembered how for years you would call me on a Monday afternoon, and I could tell from the tone of your introductory “John” which it was going to be. One wonders if one would want to live one’s life over; maybe it would be too exciting. . . .

Best,

John

To William Shawn

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

January 13, 1987

Dear Mr. Shawn:

I was sorry to hear from Roger [Angell, a New Yorker editor and writer] last night and from The Boston Globe this morning that you will be leaving as of March 1st. The period of your editorship and my contributorship are much the same, and in that period The New Yorker and its kind encouragements and indulgences have formed the center of my literary life, and my life in general. Without your taste and generosity my life would be unimaginably different, and I still remember well those days in the mid-fifties when you welcomed me to the offices and gave me the exhilarating responsibility of a fraction of “Talk of the Town.” When I left in 1957, I rather imagined I would be back, to my steel desk and sharpened pencils some day; and though that day never came the possibility of it has always comforted my lonely freelancerhood. It’s hard for all of us to picture the magazine without you at the helm, each week’s contents sifted through your amazing receptivity and scrupulousness. Perhaps now you will favor us with writing of your own. I hope so. At any rate you have my gratitude, great admiration, and best wishes.

Sincerely,

John

To Roger Angell

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

July 18, 1988

Dear Roger:

Thanks for your nice consoling/encouraging letter with the last rejection; I hadn’t even faintly expected you to take it, so the blow didn’t need to be so considerably cushioned. Actually, what surprises me is still The New Yorker’s taking something, not their turning it down, and if I’m come to the end of my usefulness in the short story department, I’m still very grateful for the long ride I’ve had. Sometime in the early ’60s it became clear that my light verse wasn’t going anywhere at 25 W. 43rd St. any more, and a few years after that I perceived that my “Notes and Comment” no longer could go with the new tone and content at the front of the magazine; so I’ve died a few deaths already. “The little death that awaits athletes” is a phrase that echoes in my mind from somewhere, and we would-be verbal athletes must greet it as bravely as the jocks.

Also, your turning down a story doesn’t make it any worse, any more than your taking it makes it better; so the effort, to please and challenge myself, remains the same. I recognize too that my generation, with which I am, loosely, stuck, is getting older, while The NYer and its editors remain ever young at heart. It’s a rare contributor to your pages, always excepting Sylvia Townsend Warner, who doesn’t fade away before the grave. So I stand ready to go the way of Kay Boyle; in the meantime, here is an especially elderly story, oddly enough. My last for a while, since it uses up my floppy disk. . . .

Best,

John

To William Maxwell

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

January 23, 1992

Dear Bill:

The funny thing is, I was going to write you. I’ve been pawing through my manuscripts at Houghton Library in Cambridge, trying to date my old poems for a collected edition, and thought the old New Yorker letters might help, and couldn’t help rereading some of the innumerable ones from you. What a torrent of encouragement and loving advice and undeserved flattery over the years! Where would I be without it? Somewhere else, I’m sure. And the sadness of thinking that you and I, you in your office with its view of Rockefeller Center and I in my Ipswich domicile surrounded by children and dinner parties, are figures of the past, characters in a drama whose scenery is all packed up and in the van. Anyway, if I’ve never said it before, thank you for all that caring and intelligence. . . .

Love to you both,

John

To Tina Brown, editor of The New Yorker

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

March 7, 1994

Dear Tina:

My goodness, who would have thought that my rambling response to a question from an intimate audience in Dallas would so quickly reverberate back on 43rd Street? I was chattily and not unreassuringly responding to one of those worried, my-age faces in the audience who like me had been reading The New Yorker for longer than was good for them. The question comes up every time I stand up at a lectern. I haven’t seen what the Dallas paper made of my remarks, but I always begin by making clear that a) you were brought in not to preserve the status quo but to make changes, and have done so with admirable dispatch and energy (b) I as a contributor have been made to feel very welcome (c) times, they are a-changin’, and ancient Gutenbergian types like me should be taken with a grain of salt. . . . Sorry if my remarks as quoted in any way have made it harder for you to do your demanding job. . . .

Best,

John

To David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

July 14, 1998

Dear Mr. Remnick:

Thank you so much for your very generous and speedy letter—how did you get your name as Editor on the letterhead so swiftly? As far as I know everybody inside the magazine and all those outside who love Eustace Tilley are thrilled at your appointment. I have been reading you on Russia ever since you began to write about it and now this week I see you have tackled the Amish, my fellow Pennsylvanians. My only thought when Ann Goldstein told me you had been named was, “Does he really want to give up writing?” There is an uncluttered egotism and serene craft in writing that I am not sure being an editor offers, especially now that Tina has made The NYer fodder for gossip and business columnists. But I guess a Princeton summa knows what he’s signed up for. Good luck, needless to say.

I will continue of course to submit what I can, while trying to carry on with my novels and whatnot. I am thrilled this week to see that a poem of mine made it into the issue. This fall, when things have cooled off, when I am in New York perhaps you would like to share a lunch with me. Tina took me to lunch at the Four Seasons, surrounded by power suits. Shawn took me to a farewell lunch when I left the premises in 1957; he ate Kellogg’s Special K at the Algonquin. Bob Gottlieb didn’t do lunch—he liked his blue jeans—but he gave me a sandwich—turkey with mayo—in his office. I’m still hungry.

You were most kind, at this busy time for you, to write.

John Updike

To David Remnick

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

February 7, 2004

Dear David:

. . . As to your kind invitation to have a fifty-years’-anniversary lunch, I gladly accept. You’re good to think of it. The question is, When? I wrote the first things The NYer took in June of 1954, and the poem was run, as I remember, in August. But August is perhaps a poor month in which to rally the staff. Do you want to jump the gun to this April or May, or wait until November or mid-October, when I’m back from Europe and your festival excitement has died down? The people I deal with are not very many—[Henry] Finder, Roger, Ann G., Leo Carey, Alice Q[uinn] once every blue moon. The editorial ghosts sitting around the table will be numerous, going back to Mrs. White and Shawn and Maxwell. It would never have occurred to them to do anything of this sort, but these are more ceremonious times.

As to your kind words, I am like those ballplayers who didn’t have to take time off for war or players’ strikes. I just kept plugging along. No plaudits due. My sense of it tells me that White and Thurber, Salinger and Cheever meant more to giving the magazine its image and panache, but I did what I could, and loved the magazine with an adolescent crush that never let up, and am thrilled to have the present editor’s good opinion, and to still be printed in those glossy pages.

All best,

John

To Catey Terry, a student at the Missouri School of Journalism writing her master’s thesis on The New Yorker. In a letter to Updike of March 20, 2004, she asked if he would write for her a paragraph on what it was like to work with various editors at the magazine. (Mistakenly, he addressed her as “Mr.”)

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

April 3, 2004

Dear Mr. Terry:

I myself didn’t go to graduate school, because I didn’t want to write a master’s thesis. So let my help with yours be minimal. Please understand that only for two years (1955-57) did I work in the offices of The NYer, as a “Talk” writer, and my relation with the magazine has been that of a contributor, and a book reviewer, neither of which brought me much contact with the editors-in-chief.

[Harold] Ross died when I was in college, so I never knew him. My impressions of Shawn were written out when he died, with a brief piece you can find in my collection More Matter. He was quiet, laconic, courteous, slyly droll, and very kind and encouraging to me, expressing himself through other editors. He was a saint of sorts, and like many saints eventually wore out his welcome. Gottlieb I knew as editor of Knopf, and so his advent held no terrors for me; I declined to sign the petition against his appointment. I thought he did a fine job for the magazine, bringing it up to date in some respects (expanding the front section, lifting the long ban on dirty words), and he was fired, as best I understand it, for refusing to change the magazine as drastically as S. I. Newhouse wanted it changed.

Tina did change it, not for the better in all respects—those of us who loved the old format winced at her less discreet modifications—enlarged the title type, tarting up the Eustace Tilley cover—but she did get the magazine a lot of attention and I wonder if our present sense of its being indispensable doesn’t have something to do with her. She brought it into the Condé Nast mold enough to preserve it, its red ink notwithstanding. I can still picture Tina in her little black dress and hear her incisive English voice twittering away. She made the magazine a happening, for better or worse. David Remnick is as much a gentleman as Shawn, with the same roots in the journalistic side of the magazine. . . . He has a lot of quiet energy and seems to have brought peace to the editorial staff and to the subscribers. I wish the cartoons were drawn better, but otherwise have no complaint, only praise. He won my heart when he wanted to serialize the last of the Rabbit installments; Rabbit began as something I wanted to write at a distinct distance from my NYer work, as something quite other.

Enough? Surely. . . .

Best wishes,

John Updike

To Henry Finder. In a letter of December 12, 2008, accompanying the galleys of Updike’s review of a new John Cheever biography, Finder wrote, referring to Updike’s recent diagnosis of Stage IV lung cancer: “I realize that this winter is bound to be an especially dark and difficult time. But I hope you know how much admiration, even adoration you inspire from these Manhattan precincts. Everyone who’s had an Updike piece pass through his or her fingers en route to publication feels a bit of a tingle—like touching a magician’s silks.”

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

December 23, 2008

Dear Henry:

What a beautiful, masterfully kind letter! You know, I have never received one from you before, in all these years; I had written you off (so to speak) as a transcendentally hyper-literate who disdained all non-telephonic communication. It turns out that you are a wizard of phraseology, so much so that I blush to think how some of us have taken advantage of a talent that should be devoting its editorial attentions to its own encouragement. Thank you for your exceedingly gracious evocation of my magician’s silks while brandishing your own. Your letter completes our stimulating and fruitful relationship these several (many?) years.

I have been honored to have been one of The NYer’s book reviewers from [Ann] Fadiman to [Edmund] Wilson and up to [Adam] Gopnik and [Joan] Acocella and [Louis] Menand and the formidable James Wood. It’s been a tingly business for me, offering so many opinions in print, and the exposure and income has been highly welcome. It’s a sideline that might be, as far as comfort goes, my main line. . . .

With much esteem, affection, and gratitude,

John

To David Remnick, who had written, on December 8, 2008, “If there is anything in this world I can do for you, I will. Anything . . . You have not always been a part of this thing of ours, you are the thing itself—everything we stand for, everything we hope to be. Every writer, artist, and editor here feels that way. And so I know it’s no presumption that everyone here is rooting for your speedy, painless, endurable recovery.”

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

December 15, 2008

Dear David:

Your beautifully generous and warm letter made me begin to cry, first when my wife read it to me at the hospital over the phone, and now when I can read it holding it in my hand. I fell in love with The NYer when I was about eleven, and never fell out, and never got used to the heavenly sensations of being in print there. I know of course that my niche on the canyon walls the magazine has carved through American journalism, literature, and comic art is a mere scratching, but I have taken an inordinate pride in it, and huge pleasure in continuing to scratch away during your editorship. . . .

The Cheever review may be my last, but who knows for sure? The journey, as they say, with lung cancer is pretty much one-way, but with some loops in it, maybe, and remissions under chemo. As with life itself in its broad outlines, there is only submitting to it, and trying to be grateful for what—as much in my life does—warrants gratitude.

With great respect and affection.

John

To Deborah Treisman, fiction editor at The New Yorker

675 Hale Street, Beverly Farms, MA

January 10, 2009

Dear Deborah:

. . . I suppose of the many things I have tried to write, short stories have given me most gratification and unqualified pleasure. I am glad that what looks to be my last book, to be published this June, is short stories, called My Father’s Tears, probably the best of the bunch. But I would feel less happy about the collection if you and your editorial colleagues had not allowed me to cap it with two New Yorker acceptances—the little suburban fling in the power outage, and the rambling reminisce about happiness and sex and water and the little journey of a NE American life. I feel much happier about a collection that begins and ends with The New Yorker, where I began and ended.

I don’t know how I can rise to your lovely invitation to write more. My focus is down to the ignoble little health annoyances that seem to cap and even eclipse a major setback. But hospitals are determined these days to keep you going as in a marathon and my days do seem long and wasted with no writing in them, even though the keyboard skids about under my fingers. My country ancestors promised me a long life, but it looks like the British stalwarts—Pritchett, Trevor, Townsend Warner—will keep the prize. I’m glad I got my old guy story in early, before I was really 80. . . .

All my best wishes to you,

John ♦

This is drawn from “Selected Letters of John Updike.”

Sourse: newyorker.com