Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In October, 2020, the Russian director Dmitry Krymov staged his own version of Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town” called “Everyone is Here” for the Moscow theatre School of the Modern Play. At the time, Krymov didn’t know that Russia would launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, nor that after he signed a public letter criticizing the war a temporary work trip to Philadelphia would become permanent exile. Yet “Everyone Is Here,” a video of which floats around the Internet, still seems very much like a farewell.

A digressive, at times almost witchy reënvisioning of Wilder’s plainspoken classic from 1938, it begins with a real black cat slipping through a door before the play’s familiar characters materialize in swirls of smoke. After a few dreamlike scenes, a man in a cable-knit sweater and sneakers interrupts the action, claiming to be the director. Krymov, or rather his avatar (played by Aleksandr Ovchinnikov), tells the audience that he has been reconstructing a touring American production of “Our Town” that he saw in Moscow when he was eighteen. He reminisces about his past, introduces his long-dead parents, and reënacts spreading an old friend’s ashes, struggling comically with the urn. Eventually Anton Chekhov (two actors in a trench coat) visits the Sakhalin penal colony. Wilder would never have recognized it.

Or perhaps he would have. The sixty-eight-year-old Krymov, who often writes his own adaptations, assumes the American playwright’s cool-eyed stance toward the inevitability of loss, exhuming his own past in the process. Krymov frequently drills into the work of a great artist—Tolstoy, Pushkin, Chekhov—only to break into his own autobiographical substrate. There’s grief down there, but also a great deal of comedy. His critically acclaimed productions, full of antic puppets and rousing folk music and the occasional surprise volleyball game, recall a circus fairground at night, a wild, inviting darkness where all the buskers are ghosts. “Everyone is Here” was nominated for five Golden Mask awards, the Russian equivalent of the Tony, but once Krymov became persona non grata his name disappeared from the posters. Officially, at least, no one was there.

And now Krymov is here. Close to a million Russians have emigrated during the war, flooding into surrounding countries, but unlike some of the other openly anti-Kremlin superstar directors, who fled to Europe or Israel, Krymov has come to the United States. This month, he opens a double bill at La Mama, in New York, called “Big Trip,” which consists of two programs on different nights: “Pushkin ‘Eugene Onegin’ in our own words,” a reimagining of an old Krymov piece, and “Three love stories near the railroad,” a new, tragicomical triptych that adapts three texts by Eugene O’Neill and Ernest Hemingway. His first production in New York since a tour of his expressionist “Opus No. 7,” in 2013, “Big Trip” will also serve as proof of concept for a newly formed theatre company, a body of mostly young, mostly American artists called Krymov Lab NYC.

La Mama, in the Bowery, isn’t just Off Broadway, it’s Off Off. In early September, a few weeks before opening night, Krymov met with his small company in La Mama’s rehearsal complex on Great Jones Street, in one of a stack of low, tin-ceilinged rooms where avant-gardists have been rehearsing for half a century. The actors, who had been on break for the summer, were trying on costumes for the first time. They had been rehearsing on and off in the course of a year, and had held a chaotic series of showings in December. (The night I saw it, an audience member took a prop and refused to give it back.)

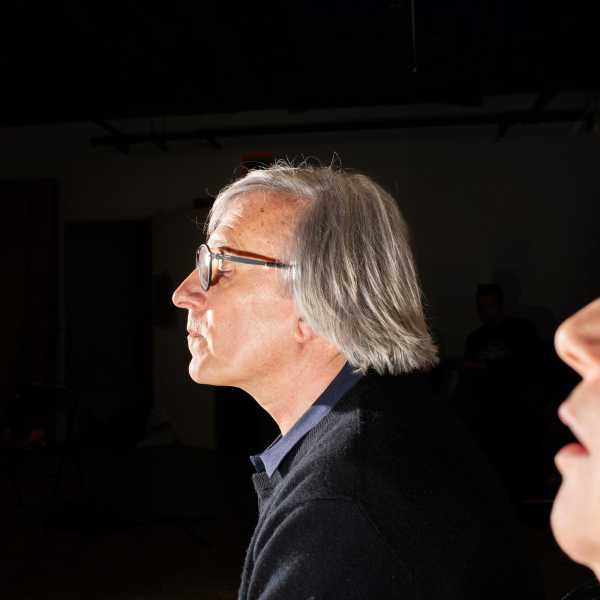

Krymov (Dima to his friends and admirers) is a large man—not tall, exactly, but bear-on-his-hind-legs imposing—with a wispy, silver Prince Valiant haircut framing a face that’s moon-calm and smooth. His glasses, which have an aviator-style bar across the top, make his eyebrows look perpetually raised. His English is solid and idiomatic, though he sometimes chooses to speak through an interpreter, his lead producer Tatyana Khaikin. He’s never as puzzled as he seems to be.

It sometimes takes only a glancing contact with Krymov’s work to make a fan, even an acolyte. The actors and designers in the Lab have come together by a number of paths—several are from Yale’s drama school, where Krymov has guest-taught and directed, and some trained in Russia, encountering his work in its original habitat. One of the Lab’s producers and performers, Tim Eliot, for instance, was a student in the American Repertory Theatre’s Institute for Advanced Theatre Training, which, when it was still running its graduate program, conducted a semester in Moscow. There he saw “Opus No. 7,” was “thrilled and awestruck,” and, a decade later, fell into Krymov and Khaikin’s orbit in New York, when Krymov was teaching at the New School. (I was in an earlier class of that same A.R.T. program, but I first saw a Krymov piece in Poland, in 2009, at the Dialog theatre festival in Wrocław. “Opus No. 7” was a hot ticket, and I watched it sitting on the floor, crammed partly under someone’s folding chair.)

During that September rehearsal, several Russian friends and supporters—including Krymov’s wife, producer, and muse, Inna, and Isaac Koyfman, a lawyer and theatre aficionado turned president of Krymov Lab NYC’s newly formed board—were crammed into the back half of the room. The company’s costume designer, Luna Gomberg, owlish behind huge glasses, was sewing feverishly next to a costume rack, on which a black-and-white picture of Inna’s laughing face hung on one side, with the women’s clothes, and a mask of Dmitry hung on the other. Inna (tanned, tiny, peripatetic, brilliant) was chortling about Krymov getting stung by a jellyfish in France. “The last kiss of summer!” she told me.

Krymov Lab NYC rehearse at La Mama in the Bowery.

For the first section of “Three love stories near the railroad,” a clown-inspired dramatization of Hemingway’s short story “Hills Like White Elephants,” Krymov was directing Jackson Scott, an actor who is also a gifted flamenco guitarist, on how to act like a director (though not a Krymov avatar, this time). Scott was rehearsing the prologue in which he introduces the audience to the set—a table and chair and a sad cardboard slab meant to represent a second chair. Almost immediately Krymov popped up to interrupt him. “You are the director! There was supposed to be a chair! You think, All staff are lazy like usual, but you are very polite. . . .” he said to Scott, demonstrating the tight smile and chopping hand motions he wanted. He then told an anecdote about the chansonnier Jacques Brel—“He was singing a song when the sound in the mike went out. He finished the song, ‘da da da,’ and then walked offstage and began to Beat. The. Sound. Man.” He mimed a vicious walloping. Scott waited for the story to get a little less violent, but that was all. In Scott’s second run-through, his gestures did seem more vigorous.

This direction was explicit, but Krymov often tells his actors what he wants in more elliptical terms. He might say to a performer, as I saw him do in April, your character “turns humiliation into poetry in front of your eyes.” Anatoly Beliy, a lead actor of the Moscow Art Theatre of Chekhov, starred in one of Krymov’s Moscow productions and describes this lyricism as his “bird language,” a Russian expression that means a gibberish that only those intimately familiar with it will understand; performing for Krymov, he says, is a process of learning to speak it. Krymov’s style offers either free fall or freedom, an intoxicating sensation for some performers. “He treats actors in rehearsal like professionals—‘you have your “acting kitchen” and it’s your kitchen. I won’t butt in,’ ” Beliy told me. Krymov would say, “You don’t have to ask me, just—you know, just do it.” (Beliy, who was born in Ukraine and was one of the most famous theatrical and movie stars in Russia, left soon after the war began. He is now living in Israel and performing for Russian-speaking audiences.)

In rehearsal, Krymov was laughing with the actors, but he was also constantly asking for the impossible. There was even some literal bird language: Krymov told Scott that he should introduce the components of “Three love stories” as “chicken without salt, chicken with salt, and chicken with sauce.” The statement passed unremarked as, in short order, a set piece collapsed, and the sound designer tested a loud train whistle. What had Krymov meant? Was this an actable note? I never found out. By the time the set got put back up, the circus had already moved on.

Krymov was openly critical of Putin before the war, but, even after he signed an open letter protesting the “annexation” of Crimea, in 2014, he was largely left alone by the authorities. “In all the years I was working in the theatre, the past twenty years, nobody ever told me what I’m allowed to do,” he told me. “I never experienced censorship in my life as a director.” His producer, Khaikin, though, told me that the first Dmitry Krymov Laboratory, which was in residence at Moscow’s School for Dramatic Art did break up some six years ago, after Krymov found his group being edged out of favorable performance slots and pressured about content. Reportedly, at the time, he quoted the writer Andrei Sinyavsky in an address to the audience, essentially equating himself to a famous Soviet dissident.

Working as an independent director, going from theatre to theatre, in the past decade, Krymov reached something like cultural ubiquity. He had won numerous Golden Masks, and was regularly fêted at international festivals. The scholar Anatoly Smeliansky, the former literary head of the Moscow Art Theatre, noted that in early 2022, Krymov had so many productions happening simultaneously that he would sometimes lose track. “Dima got into a taxicab and realized he did not know which of the five theatres he was working in he was supposed to go to,” Smeliansky said.

On February 25, 2022, the day after Russia invaded Ukraine, Krymov flew to the United States, ready to resume work on a production of “The Cherry Orchard,” which had been in development at the Wilma Theatre in Philadelphia. It was on his way to the airport that he co-signed the letter protesting the invasion. Once he and Inna landed, Krymov came to understand, through friends and frightened colleagues, that he should not return. “It was absolutely impossible to go back and work there because people who were there understood my attitude toward everything that was happening, and I wasn’t hiding it,” he told me. He gave an interview to Voice of America, in which he compared the invasion to the horrors of the Second World War. He had nine shows playing in different theatres across Moscow, and seven of them were summarily shut down. “For some reason,” he told me, “they left two shows, and they said, ‘If you want the show to run, your name should be taken out of the poster.’ I said, ‘Of course.’ ” Those shows, too, are gone now.

“The entire company is an endless improv,” Eliot says of Krymov’s process. “We’re all following the lead conductor of the improvisation.”

Smeliansky calls the flight of so many important directors—ten or twelve, he guesses, from Moscow and St. Petersburg—a “catastrophe for the national theatre.” He likens it to the Soviet expulsion in 1922 of intellectuals on the so-called Philosopher’s Ship. “Lenin sent out of Russia the greatest Russian scientists, philosophers, and he cut the head off the country,” Smeliansky says. “It is like that time.”

In Krymov’s first season of expatriation, he went to Latvia, France, Israel. State-run theatres, with their year-round companies of actors, predictable funding, and, in some cases, Russian-speaking audiences, still want Krymov’s heady mixture of literary elaboration and toybox visual invention. But he chose to be based in New York. He speaks English; he has friends here; he has taught and worked on the East Coast. Still, it’s been a bit of an adjustment. When he asks for a few chandeliers in a state-funded theatre in Riga, they materialize. In the U.S., he wakes up thinking about how to raise cash for his tiny production, one twenty-dollar bill at a time. (The group has raised many of those twenty-dollar bills, actually. Thanks to small donations, two large gifts, and foundation grants, the budget is now four hundred thousand dollars, and well on its way to being covered. The entire run of “Big Trip” is sold out.)

In many of his works, Krymov adopts the standpoint of a young boy: “Seryozha,” his 2018 adaptation of “Anna Karenina,” was named for Anna’s son, Sergei; his pointedly political rewriting of Chekhov’s “Seagull,” from 2021, is titled “Kostik,” a diminutive of Konstantin, the play’s callow hero. It’s possible that Krymov identifies as a perpetual child because so many in Russia think of him as the child of his famous parents, the director Anatoly Efros (born in what is now Ukraine, in 1925) and the critic Natalya Krymova. Efros, in particular, was an era-defining figure in nineteen-sixties Moscow, during the Khrushchev thaw, and in the return to rigidity that followed. He was a subtle modernist interested in characters’ psychology (an emphasis on the individual psyche had been ideologically repressed under strict Communist dicta), and he helped to popularize the rehearsal use of “études,” or independent improvisational studies, a technique devised by Konstantin Stanislavski in the nineteen-thirties.

In an étude, actors are asked to devise actions or sketches of behavior supertextually: how Hamlet might behave at his uncle’s wedding buffet, for instance. Elaborate game-structures also underpin Krymov’s process, and there’s a sense that the script may never be fixed: “The entire company is an endless improv,” Eliot says. “We’re all following the lead conductor of the improvisation.” In the La Mama rehearsal studio, I watched his company spend five minutes blowing on a feather, trying to keep it in the air, to represent the communal effort and delicate silliness of theatre. There are other, sadder parallels between father and son. In the eighties, Efros led the Taganka Theatre, after its founder, the theatre titan and defector Yuri Lyubimov, had his Soviet citizenship stripped from him. The authorities erased Lyubimov’s name from his productions, as they would do sixty years later, with Krymov’s. Efros’s ensuing conflict with the Taganka company —according to one of his biographers, James Thomas, there were antisemitic aggressions against him—may have led to his final heart attack and death.

Krymov’s grandfather, his father’s father, insisted he be given his mother’s last name rather than his father’s because he “was afraid of recurring waves of antisemitism,” Krymov says. Krymov did not immediately follow his father into directing, choosing instead to become a set designer; Krymov got a degree in scenography from the Moscow Art Theatre School in 1976, and designed more than a hundred productions—including many for his father—in his first career. Then, when Efros died in 1987, when he was sixty-one, Krymov abandoned the theatre for more than ten years to paint.

For performers, Krymov’s style offers either free fall or freedom.

In 2002, Krymov, almost fifty, joined the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts as a professor of scenography, and directed his first play. (It was “Hamlet,” professionally cast and coolly received.) While at the school, he pivoted, forming his signature Krymov Lab; his design students acted as performers and puppeteers. For the nearly two decades since, his theatrical works have often included a graveside moment or a cortège: there’s the ashes ceremony in “Everyone Is Here”; “Tararaboombia” features an infinite funeral parade for Chekhov, staged on a conveyor belt; “Opus No. 7” contains a surreal wake for the composer Shostakovich; and “Death of a Giraffe” creates a knock-kneed animal onstage out of pipes and cardboard, asks the audience to love it, and then buries it.

I asked Krymov why so many of his works revolve around funerals. “I remember when I started to paint—because I was a painter for many years—it was after my father’s death,” he said. “I started to paint funerals in different compositions, different fantasies. It was probably because of the very strong shock that I experienced during that time, and, somehow, it jumped over into my subconscious.”

In the winter of 2022, Krymov and his wife woke up in New York to smoke in their apartment, which had caught on fire from a suspected electrical fault. After trying to fight the flames, Krymov spent several days in a medical coma, as doctors treated him for smoke inhalation and burns. His wife and friends didn’t know if he would survive. He shrugs when he talks about it. He dealt with it the way he always deals with trauma: this summer, he went to Klaipėda, Lithuania, and devised a production borrowing from Chekhov’s “Three Sisters,” based on the act in which the sisters take in their neighbors after a fire.

Even in translation, his work is referential and allegorical, but the world he left behind in 2022 understood his references. “Tararaboombia” paraded characters from Chekhov’s plays past the audience, but it also included sly jokes, such as a train car marked “oysters.” How many people here would know, as a Russian theatregoer once would have, that Chekhov’s body was shipped to Moscow in a refrigerated railway carriage? An important part of Russian theatre is its stratigraphic effect. From their school days, audiences are steeped in the meanings and changing interpretations of theatrical texts, which allows them to read a production as a series of layered transparencies. At New York’s City Center, I once saw a Russian production of “Eugene Onegin,” by Alexander Pushkin, directed by the Lithuanian Rimas Tuminas, that baffled me—one actor was playing a rabbit, and I finally had to ask a Russian seatmate about it. Legend has it that Pushkin saw a rabbit in the road as he was on his way to participate in the doomed Decembrist Revolt; he thought that it was a bad omen, so he turned back, saving his life. So a show’s jokes and talmudic references might well stay opaque, if you don’t know both the text and the commentary around the text.

Because Krymov’s work primarily operates through image—the critic Viktor Beryozkin grouped him with other highly visual directors like Robert Wilson and Tadeusz Kantor in “the theatre of the artist”—it has been received well in New York despite the audience’s lack of shared literary context. “Opus No. 7” came to St. Ann’s Warehouse, in 2013, where it was rapturously received. There was a time when you could see quite a bit of work by Russian directors in New York: Piotr Fomenko’s “War and Peace” came to Lincoln Center in 2004; the Foundry helped Kama Ginkas restage “K.I. from Crime,” an elaboration on a moment from “Crime and Punishment” put on in a midtown freight entrance, in 2005; Lev Dodin brought several of his epic, elegiac productions to Lincoln Center and Brooklyn Academy of Music, most recently in 2018. But it didn’t take a war or a pandemic for that contact to lessen—such cultural exchange was already dwindling in the wake of increasingly stringent visa requirements and fading institutional support for overseas work.

“Pushkin ‘Eugene Onegin’ in our own words,” the first part of the La Mama diptych, begins with a band of travelling Russian players, grumbling and frustrated with their performing conditions. When Krymov spoke to his cast in April, before they spent the summer apart, he tried to explain to them how to play these Russian immigrants. “I know what it means to be an émigré,” he told them. “I know but I won’t share. It’s scary. It’s like you’re standing like this and behind”—he mimed a cliff at his heels—“everything has dropped away.”

The audience receives puppets that look like children, which sit on their laps. The troupe talks directly to these loaned-out, artificial boys and girls, explaining everything from what a ballerina does to who Pushkin was, which turns the event into a kind of children’s educational theatre. “Eugene Onegin,” of course, isn’t really for kids. It’s a sorrowful nineteenth-century epic about the impossibility of recovering the past. The jaded aristocrat Onegin spurns the affection of a country girl, Tatyana, and then, years later, reëncounters her, now the wife of a general, in the soulless glitter of high society. She rejects him, though she loves him, mourning her lost innocence. The puppet-children allow the audience to watch the show as if through children’s eyes, vicariously experiencing, at least dimly, the sensation that Tatyana says has been lost forever. In the nineteenth century, the Russian literary critic Vissarion Belinsky called the novel in verse an “encyclopedia of Russian life,” and the view hasn’t changed much since—Tatyana’s despair and nostalgia are still central to how Russians see themselves.

There’s a hint of defensiveness in staging this now, of course. Russian culture is being reëvaluated and challenged as part of global anger about the invasion. When I asked a friend and theatre critic, who has been a passionate advocate for Krymov’s work in the past, to speak with me about his career, he refused even to discuss him, pointing me instead to Ukrainian theatremakers. (Even fictional Russians are too radioactive for some creators: the author Elizabeth Gilbert pulled her period novel “The Snow Forest,” citing Ukrainian sensitivities.) Is there a place for Russian theatre? “The desire to destroy everything Russian on a national basis is also nationalism,” Krymov wrote, when I asked him about whether he was sensitive to these protests. He sees the work that the Lab is doing as hybrid—Russian theatre mixed with all the other influences that have immigrated into the room. Yury Urnov, one of the artistic directors of the Wilma Theatre and also a Russian-born theatre director, has struggled with just this: “It’s a very painful moment to associate yourself with Russia, but then dissociating is dishonest,” he says. In Krymov’s work, one encounters a “matryoshka of contexts,” Urnov says, which can be understood “in the context of this company, in the context of the war, in the context of his immigration, or—whatever it is, I don’t know how to formally name it—immigration. Exile.”

Elizabeth Stahlmann, an actor who followed Krymov from the Yale Drama School, plays Tatyana, and she says that when Krymov first showed “Onegin” to the new Lab, he acted out the entire play, reading the script and demonstrating the blocking, playing all the parts. Toward the end, Tatyana delivers a monologue. “It’s one of the only times in the play that we actually use Pushkin’s words,” Stahlmann says. “So he sat down, and he gives this monologue in Russian, with Tatyana [Khaikin] translating—and he transforms. He’s an incredible actor, and he starts crying. It’s about leaving. For him, it was about not being able to go back, not being able to go back to Russia.” Then Stahlmann quoted Krymov reciting Tatyana’s speech: “That’s where my parents are buried. I will never see their graves again.” She, like many actors before her, was discovering that she would be playing a version of her director onstage.

“And then he goes—‘O.K., you do it now.’ ” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com