Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The ferry ride from Rockland, Maine, to Vinalhaven takes a little more than an hour, and on a clear, bright July day, half of the passengers decide to sit in an interior cabin, away from the rays of the sun. From the deck, you can see the three wind turbines on the northwest part of the island; they sit near what was once the only house that was visible on the shoreline of this part of the island, a three-story cottage, with no electricity or running water, that was once called the Only House and owned by the children’s-book author Margaret Wise Brown.

Brown, the author of the classics “Goodnight Moon” and “The Runaway Bunny,” spent summers at the cottage between 1943 and 1952. From her writing desk, on the second floor, she could see a tiny, spruce-topped island. The illustrator Leonard Weisgard, who visited Brown in Vinalhaven numerous times, remembers falling asleep one night in the Only House’s ground-floor workshop, only to be awoken by a loud banging above him.

“Margaret was shouting, ‘Leonard! Quickly, look out your window!’ ” he wrote in a remembrance of Brown, who died at forty-two, from a pulmonary embolism. “The first morning sun was shedding its golden light over the sea and onto the little island beyond The Witch’s Wink. The little island seemed to be brushed by gold. Even the sea was golden. This effect did not last long. Clouds billowed past and the sun’s light changed. Everything here out on the sea moved and changed from moment to moment.”

Margaret Wise Brown’s island home, the Only House, in Vinalhaven.

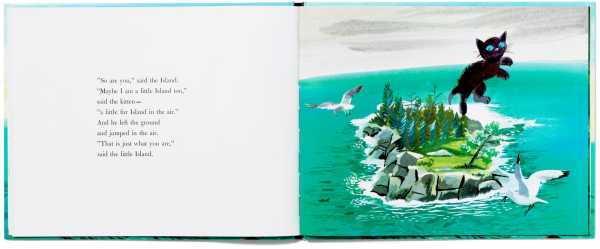

A spread from “The Little Island.”

Vinalhaven is coastal Maine at its freest and perhaps its finest. It suited Brown, an adventurer for whom traditional heterosexual womanhood and domesticity didn’t hold much appeal. She explored the world around her with curiosity and amazement, going abroad or spending quiet days on the island, watching the tides roll in and bees somersault off spring flowers. Brown once wrote that this was “Cat Life—which means doing nothing and just watching.” James Stillman Rockefeller, who was engaged to Brown at the time of her death, recalled that, on Vinalhaven, Brown would radiate “the elemental dignity of a wild animal free in its native habitat.”

The granite outcropping that so enchanted Brown and Weisgard is called Pole Island. They captured it in the 1946 book “The Little Island,” in which Weisgard draws the island, the book’s stalwart protagonist, as rocky and diminutive, with a bit of greenery. (The book’s other major character is a curious black kitten who takes a boat trip to the island and engages it in conversation about the meaning of life.) In the book, there are about a half dozen trees on the island. Today, it has more vegetation. Things change. They grow up. And die.

As Brown put it:

Nights and days came and passed

And summer and winter

and the sun and wind

and the rain.

And it was good to be a little Island.

A part of the world

and a world of its own

all surrounded by the bright blue sea.

Pole Island, near Vinalhaven.

I grew up in Northern California, but islands off the coast of Maine played a central role in my youth. They were the settings of the books that I loved most, and to which I still return, again and again. These books—which include Robert McCloskey’s “Blueberries for Sal” (1948), E. B. White’s “Charlotte’s Web” (1952), and Barbara Cooney’s “Miss Rumphius,” (1982)—concern life, freedom, fresh air, and a certain feral aspect of their (mostly) female protagonists. There is also a sense of sorrow to them, an acknowledgment of the steady passage of time, and, in some cases, decline and death.

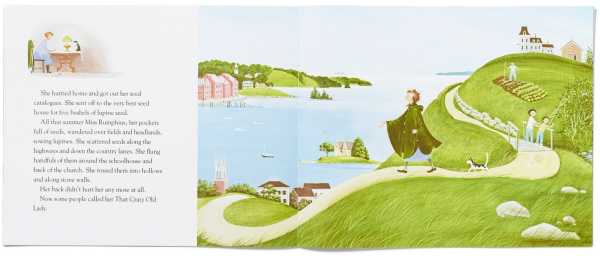

My interest in Maine began when I was about eight years old and my mother gave me a copy of “Miss Rumphius,” which follows a proudly independent woman named Alice Rumphius as she grows up, works in a library, and travels as far as Southeast Asia and North Africa. She eventually settles down in a small home in coastal Maine with a cat, a view of the islands, and a determination to “make the world more beautiful.” She achieves this by spreading the seeds of lupine flowers all over the countryside, an undertaking that earns her the moniker the Lupine Lady. There is no mention of husbands, or marriage, or childbearing; this, for me, has always been an enormous part of the appeal.

Flowers near the lighthouse at Owls Head.

A dead crab on a Brooksville waterfront.

The book is based, in part, on Hilda Hamlin, a real “lupine lady” who moved to the United States from England in 1904, went to Smith College—which Cooney also attended—and settled on the coast of Maine, where she spread the seeds. Big-leaf lupines, Katherine Brewer, a curator of living collections at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens tells me, are a non-native species. Some consider them invasive. But they’re beautiful nonetheless, exploding in hues of purple and pink, which Cooney lovingly detailed, using acrylics and colored pencils on paper made of gesso-coated percale.

One early afternoon in July, I went to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, in Brunswick, Maine. There, I met curators who invited me to view the original illustrations for a number of Cooney’s picture books, including “Miss Rumphius.” I was taken aback by how she was able to render even the tiniest detail of a dog’s tongue, a girl’s braid, a blade of grass—and, of course, hundreds, maybe even thousands, of lupines.

In various drafts, Cooney made notes to herself about everything from Alice Rumphius’s style of dress—Cooney considered, then rejected, putting a hat on her—to the colors of the ocean in an illustration of her protagonist’s journey to a Pacific island. Cooney learned to paint as a child and dedicated her early adulthood to perfecting her craft as an illustrator. Later, she had four children of her own. “She taught them to see what she saw,” Sarah Mackenzie writes, in a recent picture book about Cooney. “To love what she loved, to take in the delicious wild world.”

A birdhouse outside Barbara Cooney’s home.

At one point in the early nineties, the children’s-book author and former bookstore owner Barbara Burt took her eight-year-old daughter, Nita, on a children’s-book tour of coastal Maine. Their journey was inspired by the wanderlust of Miss Rumphius, Burt later wrote, but the world that Barbara and Nita toured was decidedly smaller: they travelled about a hundred miles north, from Newcastle to Blue Hill, in the course of four or five days, ending up in Brooklin, the home of E. B. White.

Earlier this summer, I took a similar trip, beginning in Portland and ending on and off the Blue Hill peninsula, where White and Robert McCloskey both lived and worked, looking to explore the places that had meant so much to me as a young reader. I was drawn to Maine because of what it represented to me, both as a child and as an adult: a place where a person could indulge her curiosity about—and desire to experience—the natural world while also enjoying a kind of creative solitude; a place where books get written and paintings get painted and fox kits and fawns play in the meadows outside. I had first visited Maine in my early thirties, when I was living in New York. By 2016, I was going there every summer, entranced by the freshness of the air, the clear waters, the rolling hills and low mountains, and, most of all, the islands, which reminded me of the view from Miss Rumphius’s cottage.

An illustration from “Miss Rumphius.”

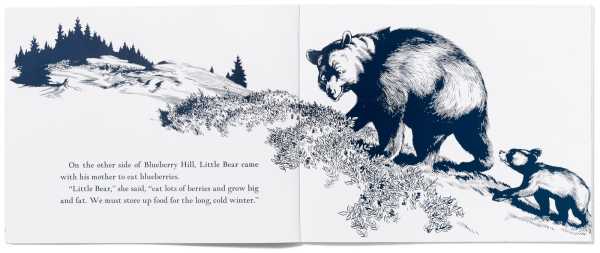

I started my journey with a visit to Peaks Island, a short ferry ride from the coast of Portland, past seals and great blue herons floating in and above the dark-blue water. There, I met Scott Nash and his wife, Nancy Gibson-Nash, the founders of the Illustration Institute, which exhibits the work of famed illustrators and offers residencies to visiting artists from around the world. Last year, the institute, with assistance from McCloskey’s family, put on an exhibit of his work at the Curtis Memorial Library, in nearby Brunswick. Left behind was an enormous mural on the curved wall of the library’s main staircase: a reproduction of a page from “Blueberries for Sal,” showing a mama bear, cub in tow, making their way up a sloped blueberry field.

Nash said he was delighted and surprised by the turnout for the McCloskey exhibit—some eighty thousand people. “There’s so many emotions caught up with children’s books,” he told me. “There’s the nostalgia, but then the realization when you start to look at them from an adult perspective of how beautifully written they were and also how beautifully crafted the illustrations were.” Visitors, he said, were “just poring over the drawings.”

Dahlov Ipcar’s home in Georgetown.

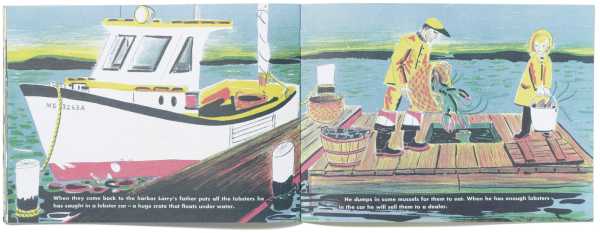

Among the most loved children’s-book illustrators from Maine is Dahlov Ipcar, whom Margaret Wise Brown chose, when Ipcar was in her late twenties, to collaborate on Brown’s “The Little Fisherman” (1945). I was not familiar with Ipcar until my adulthood, and though much of her work doesn’t depict Maine —“One Horse Farm” (1950) and “Lobsterman” (1962) are exceptions—it celebrates a certain fierceness and expressiveness, especially with regard to animals and nature. Her books are populated by flora and fauna, and some don’t contain human beings at all. One illustration, “Lonesome Loon,” from “Maine Alphabet,” imparts a strong sense of melancholy. The bird floats on blue-green waves, with its head craned skyward and its bright-red eyes taking in the appearance of a crescent moon.

An illustration from “Lobsterman.”

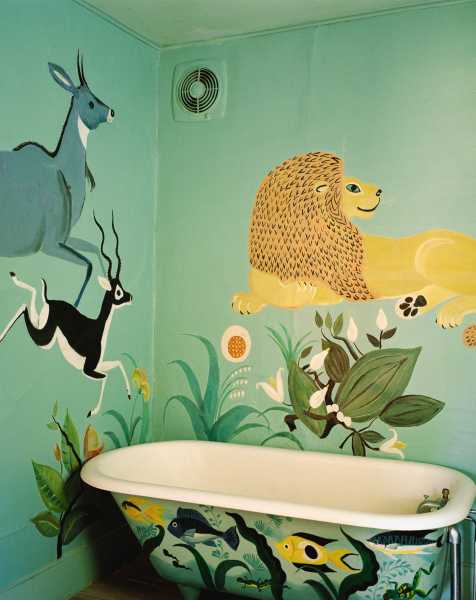

Ipcar died in 2017, just nine months shy of her hundredth birthday. Her home, on a farm in Georgetown, Maine, and the studio inside it have been preserved exactly as she left them. One late afternoon, I visited Ipcar’s farm and met her two sons, Charlie and Bob, and Bob’s daughter Julie. They showed me Ipcar’s studio, a light-filled room off the entry, where an easel stood next to a wall of windows. Later, Julie’s brother, Matt, told me that watching his grandmother paint had “showed [him] that art could be a job, and one that you could take immense pleasure in.” So, too, Matt said, had her house, with “the remnants of the nineteen-fifties childhood of my dad and uncle—cows’ names written in the barn, endless fairy-tale books, literal sleigh rides, live newts in terrariums, and even my grandfather’s rifle casually propped up next to the umbrellas.”

Dahlov Ipcar’s studio.

The painted walls inside Dahlov Ipcar’s home.

Dahlov Ipcar’s studio.

That day at the house, Julie served a meal of lobster rolls, red potatoes, corn on the cob, and blueberry hand pies. We filled up our plates and moved into the living room, where we ate from our laps on chairs and sofas, surrounded by Ipcar’s paintings and bookcases full of curiosities. A staircase led up to living quarters on the second floor, where Ipcar painted pictures of animals on some of the walls, colorful and inviting.

Ipcar’s house felt wondrous and slightly chaotic; one is not sure where to look because it’s worth looking at everything. Julie recalled that, when she was young, she was envious of other children whom Ipcar invited to play chess or have tea at the house. “But, after the other kids left, she would turn to us and ask what animals we’d like our pancakes shaped in, and all was right in the world.”

I was reminded of something that Chris Van Dusen, among the best-known children’s-book authors from Maine, said, about McCloskey’s “One Morning in Maine,” which he called “quite possibly the perfect children’s book.”

“I remember I wanted to crawl into those pages,” Van Dusen told me. “I wanted to walk across the meadow, down to the shore in the morning. I wanted to be there with that family. I wanted to live there.”

Broken pier in Bucks Harbor.

Northeast from Rockland on Highway 1, past the small city of Belfast and an artist co-op called the Lupine Cottage, is the Blue Hill peninsula. The area may be best known for being the setting of McCloskey’s “Blueberries for Sal” and “One Morning in Maine,” and, of course, “Charlotte’s Web,” the climax of which takes place at the local county fair.

Most readers remember Wilbur and Charlotte, but there’s another central character in White’s story: Fern Arable, a tomboy with pigtails and a special bond with animals. Fern is a formidable little girl, an eight-year-old who can go toe-to-toe with her ten-year-old brother, who first saves the life of the “runt” of a pig that her father is set on fattening for slaughter. Wilbur is transferred to the barn of a relative and neighbor, Mr. Zuckerman. Fern spends part of most days there, visiting Wilbur and the other animals, and overhearing—if not quite engaging in—their conversations about everything from proper comportment to Wilbur’s weight gain.

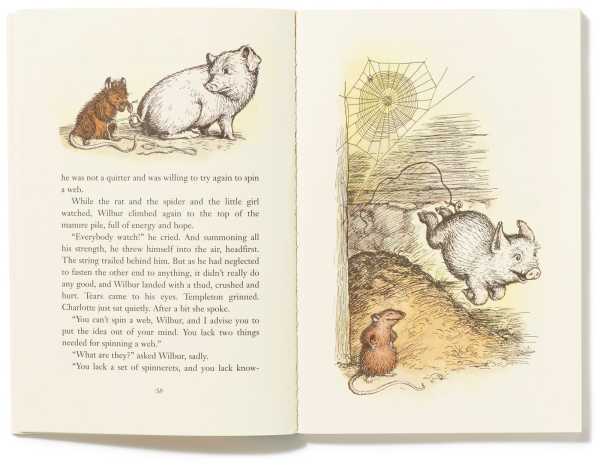

An illustration from “Charlotte’s Web.”

Fern is so devoted to her animal friends—and so insistent that they talk to each other—that her mother becomes concerned and consults a local physician. The doctor tries to reassure her. “Children pay better attention than grownups,” he says. “If Fern says that the animals in Zuckerman’s barn talk, I’m quite ready to believe her. Perhaps if people talked less, animals would talk more.”

Perhaps. But Fern herself stops paying attention. She grows up, and she begins to direct her interests elsewhere, becoming friendly with a young boy. I feel a sort of resentment toward her. Life goes on, I guess.

Life also ends, sometimes viciously. Despite Charlotte’s sophistication—somehow she has heard of the Queensborough Bridge—and her role as the benevolent matriarch of the barn, White sees to it, early on, that the spider remains true to nature. He doesn’t shrink from describing the way that she catches, immobilizes, and sucks the life out of the insects that get caught in her web—not just flies, but “grasshoppers, choice beetles, moths, butterflies, tasty cockroaches, gnats, midges, daddy longlegs, centipedes, mosquitoes, crickets.” The illustrator Garth Williams nods to this with a drawing of Charlotte wrapping some sort of unlucky bug in a cloak of silk for safekeeping.)

E. B. White’s headstone.

For the past few years, the Blue Hill Fair has hosted a “Charlotte’s Web” exhibit, with a (real) pig and a (fake) spider. Somehow, when I am talking to Erik Fitch, the general manager of the fair, we get on the subject of how he sources his Wilburs: from sperm harvested from a pig in Pennsylvania, which means that every Wilbur will be related to the Wilburs from years past. “There’s a whole science behind it,” Fitch, who handpicks his Wilburs, says. This year’s Wilbur, like the Wilbur from the book, was a spring pig. Fitch doesn’t tell me what will happen to him once the fair is over.

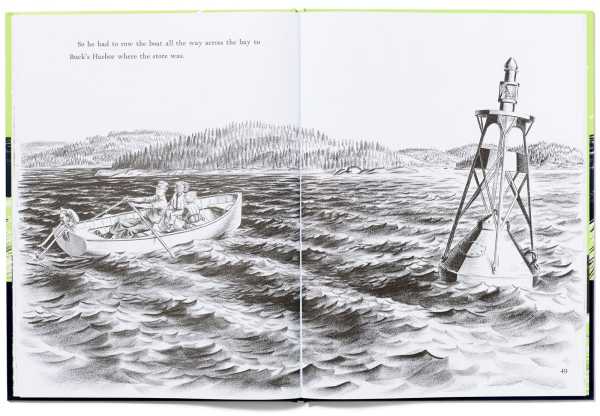

If “Charlotte’s Web” is a celebration of life in the face of death or old age, Robert McCloskey’s books are celebrations of youth and possibility. On one of my last days on the peninsula, I drive from Brooklin to Little Deer Isle; there, I take a sharp right and make my way to a cove, where I am greeted by McCloskey’s daughters, both now in their seventies, Sarah and Jane. Sarah, who goes by Sally, is the “Sal” from “Blueberries for Sal” and “One Morning in Maine.” Jane, who is about four years younger, appears in the latter book, also with her given name.

McCloskey’s Maine is perhaps my favorite depiction of the state: rugged and windswept, with overgrown meadows. Then there is the freedom of the little girls in his books. In “Blueberries for Sal,” Sal’s mother leaves her, at perhaps four or five, to wander a hill and pick fruit on her own. In “One Morning in Maine,” Sal, now a few years older, goes down to a rocky beach on her family’s island, where she communes with loons and seals and fish hawks. Although her parents are nearby in both books, Sal is allowed to be autonomous. McCloskey draws her playing under big clear skies.

An illustration from “Blueberries for Sal.”

Robert McCloskey’s island house, in Deer Isle.

From the cove, Sally, Jane, and I take a short boat ride to Inner Scott Island, the island in “One Morning in Maine,” where Sally owns a house—the same one depicted in the book. I feel as though I have stepped into one of their father’s illustrations: there are the boulders, the seaweed, the two-story shingled home with the covered porch. The two women look the part, too. Sally still has the same slightly upturned nose; her hair is bobbed and secured to one side with a barrette, sort of like it is in “One Morning in Maine.”

We eat a lunch of turkey and tomato salad on a deck outside of the house, accompanied by Sally’s family dogs. I ask Sally if she remembers how her father came up with the scenes depicted in his most famous books; she explains that he had her and Jane pose for him. “We grew up posing,” is how she put it. McCloskey said he would pay them twenty-five cents an hour to do so. (“I’m not sure that always happened,” she added.) I asked if there are any illustrations from “One Morning in Maine” which she remembers posing for, a sort of performance of a dream of childhood by an actual child. “All of them,” she replied.

An illustration from “One Morning in Maine.”

Boats and land in Brooksville.

Sally took Jane and me back to Little Deer Isle not long after we finished cleaning up from lunch. Soon, Sally was untying her boat from a float, turning on its engine, and steering it away, headed for her island home. The breeze was whipping her hair, and she looked capable and independent and free. I want to be a woman like that someday, I told myself.

I thought of Margaret Wise Brown, on a remote island, living her Cat Life, and her tales of wild seas and oceans, and great green expanses of woods and meadows and grass.

And I thought of Alice Rumphius. The character has served as the inspiration for any number of appreciations over the decades, from musings about the example she sets around moral courage and the pleasures of being alone to proclamations that “Miss Rumphius” is a lesson “in living.” In 1999, the author Susan Spano honored the book as an inspiration to women who travel solo, writing that it moved her to try to venture out into the world “with a calm mind and open heart.”

In one of Cooney’s illustrations toward the back of the book, Alice Rumphius is shown strolling along a cream-colored path, spreading lupine seeds and attracting the stares of townsfolk nearby. Damariscotta’s Second Congregational Church is at the bottom of the hill, and there’s an island in the distance in the bay. Alice Rumphius’s head is angled upward, as if she’s enjoying the scent of her own freedom. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com