Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The Polish word pestka has roughly the same meaning in English as the word “pip,” meaning seed, or stone, as in stone fruit. But it is also used to mean “easy”—something small, a trifle. The photographer Magdalena Wywrot started using the word as a nickname for her daughter, Barbara, in 2012, when Barbara was ten. It had been a big year for both of them, a year of fresh growth: Wywrot had finally left her husband and the small Polish village where they lived, taking Barbara with her to Kraków.

Wywrot had met her husband, Barbara’s father, when she was nineteen and he was forty-two. Barbara was born four years later, after which, Wywrot told me recently, “I started to change from a young girl to a young woman, and I started to see that something is wrong with our relationship. And, when I was strong enough, I decided to run away.” In Kraków, she found an apartment on the fifth floor of a sixteen-story apartment block, overlooking a wide intersection. She decided that their home would not have a television: nobody would tell them what to buy or do or watch. Though she had no prior visual-arts education, she enrolled in a three-month photography workshop run by a collective called Sputnik, where she got the idea to document her daughter’s childhood.

Their apartment is the location for most of the dark, staticky black-and-white photographs in Wywrot’s new book, “Pestka,” published by the Los Angeles-based indie press Deadbeat Club. The book spans eleven years, beginning with an image of a six-year-old Barbara asleep on Wywrot’s shoulder, years before their move, but Wywrot told me that she wasn’t interested in recording her daughter’s physical changes over time. She wanted, instead, to document her psychological adolescence. As Wywrot put it to me, her daughter was the world and she was a satellite, orbiting and watching as Barbara became her own person.

Wywrot was in her late twenties when she began photographing her daughter, but she was only just becoming her own person, too. Her youth had been strange and difficult. She grew up in Pogórska Wola, a small village in southern Poland. Her father was a stonemason and particularly skilled at making tombstones. He preferred to work at night, when there was nobody around, so in the wee hours Wywrot and her two siblings would often be put in the car and driven to cemeteries. Once there, she was put to work fetching water from the well for her father to use in mixing concrete. She was a lonely child. “I felt that something was wrong,” she recalled. “My imagination was very, very rich and I couldn’t speak with anyone about this because I felt that I did not fit into my surroundings.”

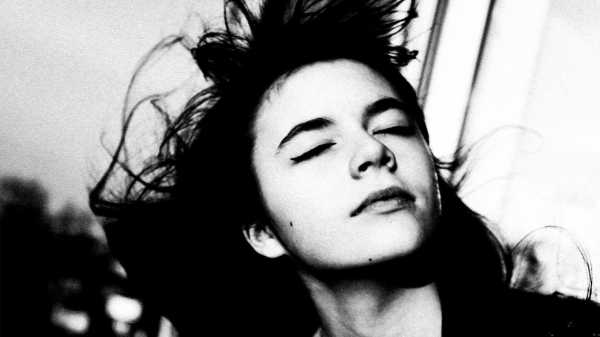

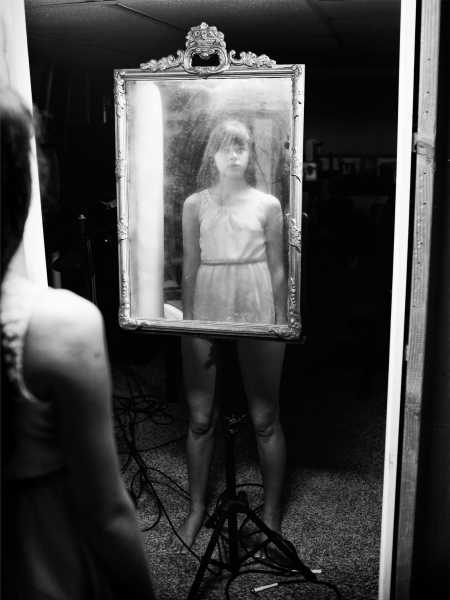

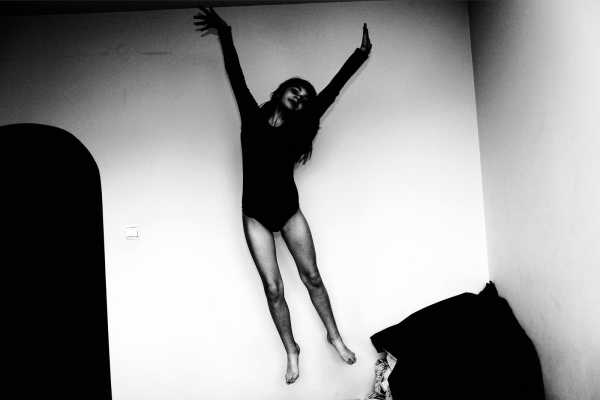

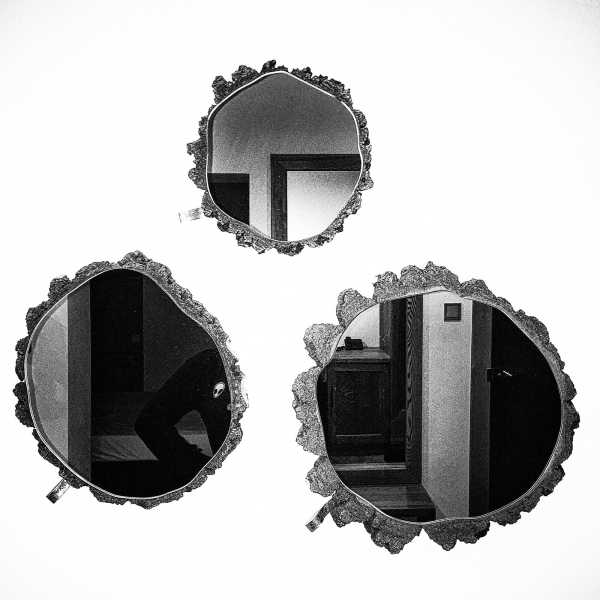

Traces of Wywrot’s gothic youth appear throughout the book: twins, shadows, night, deserted places, a large, raven-like silhouette with its features doubled by distortion. She started out using two Russian analog cameras, but she eventually switched to digital so that she could be ready to shoot at any moment. She found more influences in literature and philosophy—Dostoyevsky, Kafka, Didion, nihilism—than in photography, she says. She captured a silver reflector that appears to float like a ghost; a mirror that reflects Barbara’s head and torso but has its own legs; Barbara crouching upside down, as if hanging from the ceiling (an effect that Wywrot achieved by projecting an inverted image of Barbara onto her apartment wall); chewing gum stretched into a visceral membrane; and Barbara’s silhouette, enormous against the streets that are visible below their apartment. In this last photograph—one of several that show the girl looming large—the ground is covered in snow and the minuscule figure of a person stands as if staring up at the attack of the fifty-foot teen-ager. The glass reflects the wall behind Barbara, too, which is decorated with a portrait that Barbara painted of her mother.

The cover image is one of several that show Barbara with her dark hair obscuring her face, an adolescent Cousin Itt, hiding from the parental gaze. But many photographs seem to capture the most private moments, as if Wywrot has entered Barbara’s room without her noticing. The teen-ager jumps on her bed, stares out of the window, lies on her back with stockinged legs up against a window with the infinity sign drawn on it in what looks like lipstick. Wywrot said that, at times, she felt jealous of her daughter’s relatively normal childhood, but was mostly just happy that her daughter felt comfortable and safe—both in her life and in front of the camera. In “Pestka,” Wywrot is documenting her own newly found comfort and safety, too. Barbara told me, of her mother’s experience of those years, “In a way, it was like a second puberty, second maturing, seeing me mature.”

In the course of the project, as Barbara grew older, Wywrot’s photographs became more collaborative, and more humorous, with mother and daughter messing around, staging scenes together. Wywrot told me that when her own creative energy collided with Barbara’s, a “fever would take over” and she’d go fetch her camera. One of the last images in the book, a double self-portrait in a mirror, is the only photograph that shows both Barbara and Wywrot looking straight at the viewer. Barbara’s expression is defiant. Her arms are crossed. Wywrot holds the camera, her gaze neutral. When I asked mother and daughter about the picture over the phone, they conferred for a while in Polish. They had been visiting Wywrot’s parents in America, and had just got into a spat with them. Both women were feeling a bit like teen-agers, Barbara said: “We went to our room and locked ourselves in the bathroom and took this photograph.”

Last March, Barbara, now twenty-two, moved into her own apartment in Kraków, a ten-minute bike ride from her mother’s. This chapter of “Pestka” is over. Wywrot said, of Barbara’s leaving the nest, “Oh, it was so difficult, but it was necessary. I’m so proud of her. I’m happy that she is so talented, so intelligent, that she’s beautiful.” Barbara added, “I’m sure it was more painful for Mom than for me. That’s how motherhood works, I guess.”

Sourse: newyorker.com