By now, we all probably know how to identify “sad girl music.” It’s telling signs include being written by a woman and containing the slightest lyrical suggestion of spurned love. Zealots preemptively sound the alarm every time one of these heartbreak laureates announce a new album: “ready to cry to new music” and “hot girl summer is over, enter sad girl fall” are among the common declarations.

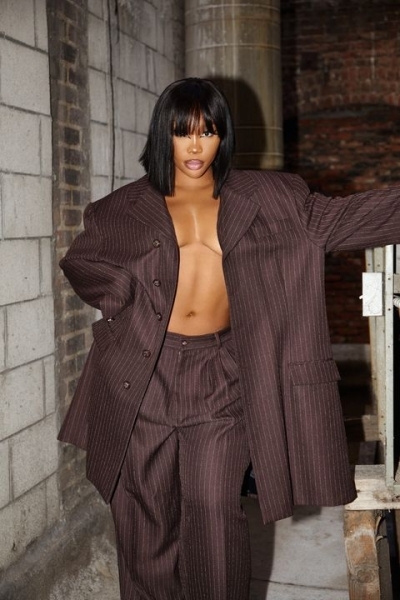

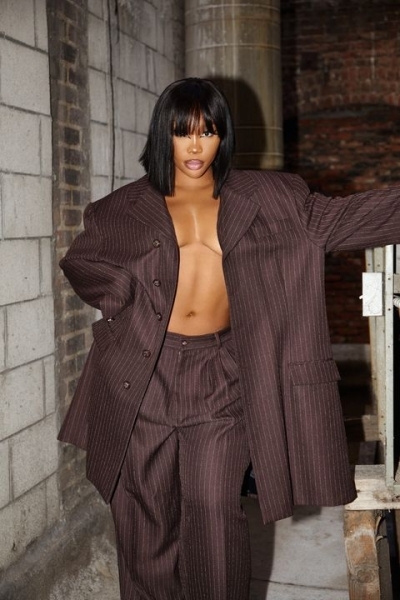

It’s a reputation that SZA, no doubt, knows well. Since her debut studio album, CTRL, sent shockwaves into the mainstream five years ago with songs that painstakingly recorded what it’s like to date ordinary men with extraordinary capacities for cruelty, she, too, has joined the mélange of musical artists neatly tucked under the “sad girl” category. Now, with the release of her highly-anticipated sophomore album, SOS, earlier this month, 23 new tracks chronicling exes, paramours, and rebounds have only expanded upon her “sad girl” qualifications—but some have interpreted these recurring motifs as a sign of emotional immaturity.

Exploring pettiness and insecurities to the point of self-flagellation are familiar themes that tie SZA’s discography together. Lyrics like “I might kill my ex, I still love him, though / Rather be in jail than alone” in SOS’s “Kill Bill” are a continuation of the train of thought SZA embarks on in CTRL (think the oft-recited “Drew Barrymore” line: “I get so lonely, I forget what I’m worth / We get so lonely, we pretend that this works”). Her propensity for vulnerable hyperboles is both a tally for and a penalty against her songwriting skills. She’s authentic for daring to say what others might rather take to the grave, or she’s superficial for writing music for so-called insecure women.

The argument goes that, in the five years that have elapsed since CTRL’s debut, SZA’s fan base has supposedly grown past the point of what SZA’s music can offer. And, if that’s not the case—if you are somehow still relating to her music—then you’re part of a pathetic pack of women whose worth is defined by the men in their lives.

Frankly, it’s a silly argument. That SZA is a human being with an emotional reality that she mines into artistic endeavors is more of an indication of her savvy as a musician and songwriter than it is anything else. But, this idea that we should only ever engage with art that speaks directly to our personal states of mind also does a disservice to both the creator and listener.

Treating any artist who ruminates about love, heartbreak, and relationships—and who just so happens to be a woman—as hysteric or hyper-emotional has long been a misogynistic dog whistle. That resentment towards women who express their feelings is all the more charged when it’s directed against a talented and confident Black woman. What are we really saying when we say SZA shouldn’t communicate sadness, heartbreak, and anger? And why do we willfully ignore her when she says feels the opposite of those things, too?

Jacob Webster

In SOS, lines of flamboyant tenacity exist alongside those of desperate yearning. “I been burnin’ bridges, I’d do it ovеr again / ‘Cause I’m bettin’ on me, me, me,” she sings in “Conceited,” before shifting gears in the next track, “Special:” “I wish I was special / I gave all my special / Away to a loser / Now I’m just a loser.” As she explained on her Instagram Story shortly after the album dropped, “It’s about being overly insecure and secure all in one. Both can coexist.”

The repulsion towards music that doesn’t directly speak to our specific point of view inevitably stifles the desire to engage with any kind of art in good faith. With that logic, why bother to read or watch anything except your own diary or the videos in your own camera roll? Is art only valuable as far as it extends to our own personal machinations and narratives?

Reducing an album as expansive and multifaceted as SOS to “side chick anthems” undermines SZA’s creative genius. It defangs her razor sharp ability to translate deeply intimate feelings into unexpected melodies that entrance and amuse as much as they induce sentiments of commiseration. Emotion doesn’t invalidate her work; it amplifies it.

What are we really saying when we say SZA shouldn’t communicate sadness, heartbreak, and anger?

This kind of criticism takes the easy way out, avoiding the task of having to take women seriously. It’s clear from SOS that SZA is an ambitious musician. Under her deft hand, she bends genres to her whim. Just look at the punk rock “F2F,” a song about rebound sex that takes influences from Paramore and Avril Lavigne, the folksy “Nobody Gets Me,” an acoustic ballad brooding over the final moments of a relationship, or her haunting collaboration with indie pop’s darling, Phoebe Bridgers.

View full post on Youtube

More than that, her ability to swing from one emotional intonation to the next with boundless aplomb showcases her skill at world building. SOS becomes a genre-bending epic about the complexities of relationships—yes, with others, but also the one she has with herself. She implores her fans to join her on an odyssey through the different phases of growing pains, reminding them that this thing we call growth isn’t so linear, after all.

In “Ghost in the Machine,” a spectral song that contemplates the soul-draining symptoms of the industry she’s made her name in, SZA pleas, “Craving humanity / Y’all lack humanity, I need humanity.” So, let’s give it to her.

View full post on Iframe