Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

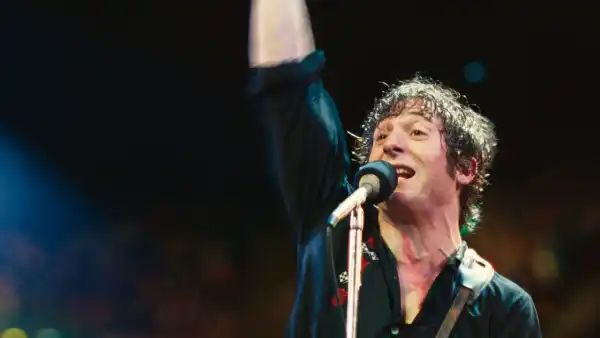

Biographical films possess an inherent struggle regarding viewpoint. Directors usually initiate such ventures out of respect, and, because of this, many rapidly shift from passion to glorification and from narrative to appeasing fans. This is markedly an issue in biographical dramas centered upon a living and still prominent public figure, whose endorsement filmmakers may seek, as much psychologically as through agreements. Scott Cooper’s biographical picture “Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere,” featuring Jeremy Allen White, serves as a key instance. Nobody anticipates a condemning biopic of the Boss, yet this movie feels so reverent and stately as to appear promotional. In its underlying concept, it mirrors another recent bio-pic about a renowned artist, Richard Linklater’s “Nouvelle Vague.” Each one is anchored on its protagonist’s creation of a singular work—Springsteen’s 1982 record, “Nebraska,” and Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 picture, “Breathless,” correspondingly—while confronting opposition to his unconventional techniques and results. However, whereas Linklater is uncompromising regarding the fractious stubbornness that Godard displayed to produce his initial film, Cooper concentrates on more personal dimensions of the musician’s tale while remaining superficial regarding them. “Springsteen” seems, primarily, like an advertisement for what was, deliberately, the least marketable of Springsteen’s albums.

This is even more disappointing considering that the components of the story—emotional health, love, artistic quest, ingrained familial pain, career pressures—are profound, intricate, and dramatic. The film commences at the culmination of a concert journey in 1981. Bruce (White) goes back to his home in Colts Neck, New Jersey, where he dwells by himself, and is uncertain what he desires to produce for his subsequent album. He lands in a painfully reflective state, re-experiencing troubling scenes from his youth—largely involving his father (Stephen Graham), who is distant, embittered, irate, and frightening, including to Bruce’s virtuous mother (Gaby Hoffmann). Bruce is portrayed replenishing himself creatively by performing at the Stone Pony, in nearby Asbury Park, and discovering insight in Flannery O’Connor’s narratives and in films, notably Terrence Malick’s “Badlands,” based upon the true murderer Charles Starkweather, who will encourage the title track on “Nebraska.” To circumvent the costly undertaking of writing melodies while in the studio, Bruce obtains a new apparatus, a compact multitrack cassette player, installed in his chamber and creates a demo on his own, of melodies to be expanded and recorded with his E Street Band. Subsequently, after he and the band make studio recordings of those melodies and other prospective successes (including “Born in the U.S.A.”), he insists on releasing the lo-fi demo tape in its unrefined condition, and distributing it initially. The business transactions are managed by his representative, Jon (Jeremy Strong)—Springsteen’s real manager, formerly and now, Jon Landau—who is the preeminent problem-solver, in professional and private spheres alike.

Bruce’s intimate life is in upheaval. He turns progressively gloomy and detached, which demonstrate to be initial indications of despondency. He also starts a connection with a lady named Faye (Odessa Young), whom he encounters outside the Stone Pony. Their romance commences with the flicker of companionship, yet the dialogue displayed between them is no more significant than her listing her favored musicians—Lou Reed, Debbie Harry, Patti Smith, and, naturally, Springsteen. There’s not a further statement concerning specifics, and scarcely anything regarding their lives. Their eventual closeness is depicted in one of the more awkward lovemaking moments I’ve witnessed lately, because it’s both excessive and lacking: a solitary side-by-side coital closeup of their countenances, in pale illumination, that may as well be substituted by a notarized affirmation stating “They had sex.” When Bruce’s conflicts with depression escalate, Faye ultimately has more to convey to him—in the screenwriters’-guide rendition of emotional abstractions. The boringly automated purpose of this bland scene is to excuse Bruce’s romantic deflections due to his ailment, the better to maintain a halo above Bruce’s head. The film’s portrayals of the miseries of depression stay understated and suppressed.

A critical moment arises during a cross-country road journey, during which Bruce’s chauffeur, Matt (Harrison Sloan Gilbertson), has to aid a troubled Bruce to remain upright at a country fair. Yet that scene, as well, is quick, conventional, and facile; it doesn’t so much illustrate a collapse as signify one. The flashbacks to Bruce’s childhood reveal that his unpredictable father similarly suffered from the condition, and those scenes are certainly, if predictably, poignant, even if Cooper resorts to the trope of presenting them in black-and-white, generalizing them, as if a nineteen-fifties youth resembled the TVs of the period. The optimal element isn’t the flashbacks’ content but their setup: Bruce regularly drives up to the dwelling where he was raised, which now appears deserted, and stares at it as if to summon recollections. In Warren Zanes’s 2023 publication, “Deliver Me from Nowhere,” upon which the movie is predicated, Springsteen is quoted as taking those drives and, he persisted, “listening for the voices of my father, my mother, me as a child.” That’s a considerably more evocative and haunting depiction than any of the portrayals in the movie.

Concerning the nucleus of the tale, the making and dissemination of “Nebraska,” “Springsteen” is both naturally captivating in its outlines and hurried and obscured in its specifics. Scene following scene exists not to observe action closely or to uncover facets of persona but to drop fragments of data that accumulate to a plot: Jon encountering an executive who anticipates Bruce’s subsequent record to be a major success; Bruce casually strumming his guitar and patting the covering of a collection of O’Connor’s narratives. Cooper offers far greater consideration to the delivery of the multitrack tape player by a colleague named Mikey (Paul Walter Hauser) than to Bruce’s endeavors to record his melodies with it. There’s very little of Bruce singing at home—barely sufficient for evidential intentions, and not filmed with any sense of enthrallment or marvel. There is no impression of what Bruce is actually seeking while he’s executing, how he devised each melody, how he supplemented the auxiliary instrumentation (all of which he himself executed) in his impromptu home studio. He requests Mikey to assist him in recording, yet their effort together in that crucial procedure is omitted.

The omissions, the deficiency of inquisitiveness in dispensing the tale, are of more than merely factual consequence; they reduce the movie’s affective scope—including its performances. White’s performance is devoted and fluent; as impersonation, it’s neither astounding nor distractingly uncanny but, rather, perceptive and sincere. Compared with Timothée Chalamet’s channelling of Bob Dylan in “A Complete Unknown,” White’s portrayal of Springsteen is unostentatious—an interpretation that suits the character of the considerably less flamboyant Springsteen. However, White as Bruce is also far less demonstrative than Chalamet as Bob, not because he’s an inherently less expressive actor but because Cooper’s writing and direction don’t grant him any adequately extensive scenes in which to cultivate the character.

Bruce not only mandates the distribution of the cassette tape’s unadulterated recordings but proffers firm conditions for the album’s launch (no singles, no tour, no press), and it’s Jon’s responsibility to relay the communication to record-company executives. The two men’s alliance of allegiance and comprehension furnishes the emotional center of the movie, yet their connection progresses largely unscrutinized. Jon implores Bruce to simply go ahead and create music. “Find something authentic,” Jon states—he will “contend with the disturbance.” Jon is a former music journalist and pundit, and in a scene at home with his spouse (Grace Gummer) he furnishes the movie’s scant lines of external perspective on “Nebraska.” Bruce is “channelling something profoundly personal and somber,” Jon states, and subsequently appends that Bruce feels ashamed regarding stardom and deserting the people from his hometown. The movie never proceeds further in contemplating the substance of the album at hand; these fleeting lines of dialogue encapsulate Cooper’s view of what the album has to articulate.

What Cooper bypasses is that “Nebraska” is, among further things, a political album. Its melodies are populated with workingmen obtaining an unjust bargain—shedding a job, forfeiting a mortgaged dwelling to a bank, owing funds, accepting labor for a criminal, bearing the encumbrance of a boss’s disapproval, being destitute and turning to transgression, endeavoring to reside with the suffering of military service in the Vietnam War. The record doesn’t solely relate a narrative of forfeiture of belief in the American aspiration; it furnishes a retrospective refutation of the notion that that so-called aspiration was ever anything more. In “Springsteen,” Bruce states that he appreciates how the demo tape sounds “from the past or something.” Far from gazing back wistfully to the nineteen-fifties, though, “Nebraska” implies that, in the existences of working Americans, there had consistently been brutality and pain lurking underneath placidly repressed surfaces—and that the pressures and burdens that he and the country were undergoing at the moment originate from the past. Cooper’s movie surely doesn’t render Bruce’s youth appearing cheerful, but in confining Bruce’s retrospective despondency to the intimate sphere, it neglects the singer-songwriter’s broader societal vision. The movie doesn’t possess the bravery of the real Springsteen’s principles. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com