Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

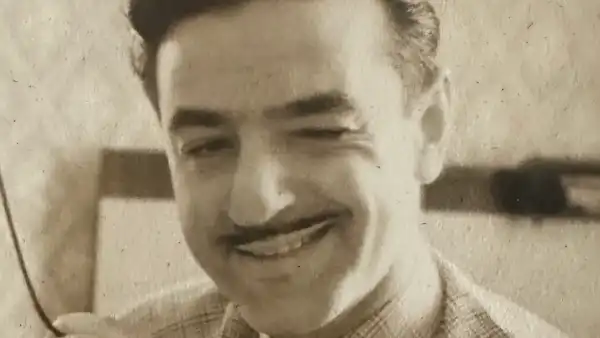

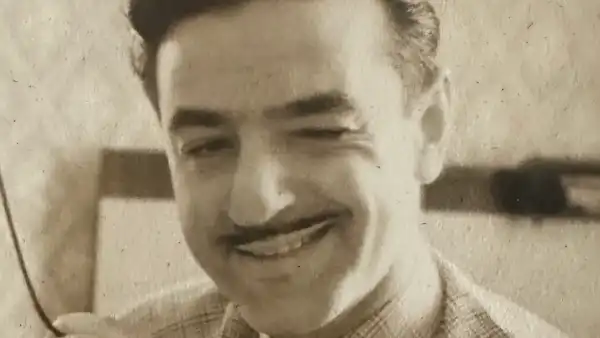

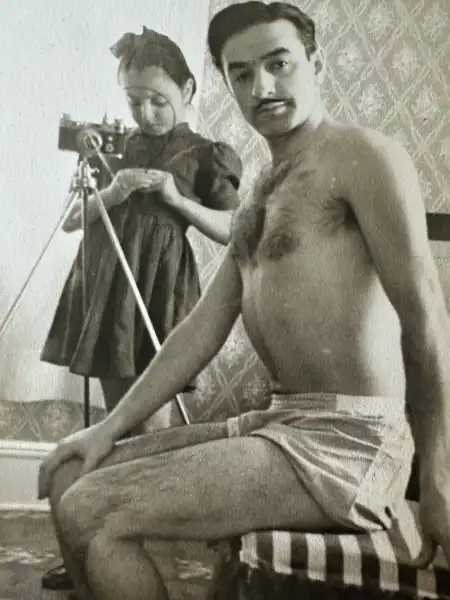

A handsome young fellow reclines casually on a bed in his Brooklyn flat, snapping a selfie. And my, has he gone to extremes. He’s positioned an antiquated plate camera on a tripod. He’s arranged a looking glass. His inky hair is closely cropped into a trendy wave. His mustache is impeccably groomed. He’s donning a textured, sleeveless white tank top.

He’s playfully posing for the lens while simultaneously attempting to appear suave, aiming to provoke a response from onlookers. He hails from Williamsburg. He embodies everything we’ve envisioned about the locale since its revitalization at the dawn of the century, metamorphosing from a run-down tenement area into the post-hipster, imitation bohemian utopia of today.

Yet, this young man doesn’t belong to that Williamsburg. He belongs to the earlier version. He’s taking this self-portrait in 1935. I’m aware of this due to the fact that he is my paternal grandfather, Eli Fuchs, and on his left sits the bassinet of his newborn daughter, Lola, my mom.

On a recent trip to my mother’s residence in New Jersey, I rummaged through some aged containers and was taken aback to discover scores of self-portraits captured by her dad during the thirties and forties: amusing ones, serious ones, blatantly alluring ones. Eli was a quiet, modest person when I was acquainted with him—a former civil servant. For the majority of his working life, he was employed at the Raritan Arsenal, in Middlesex County, conceiving, illustrating, and supervising the printing of posters, guides, and pamphlets for the U.S. Army.

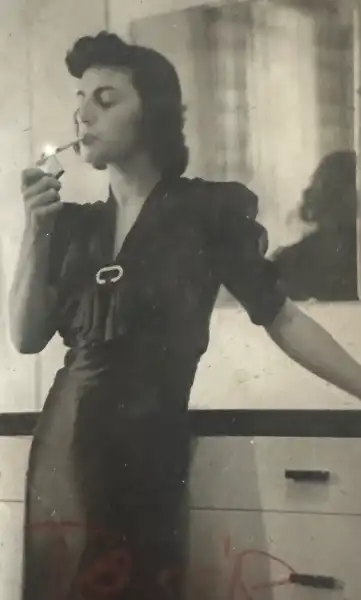

I wasn’t oblivious to his artistic inclination. Eli was a talented amateur photographer and painter. I possess an oil painting he created of me when I was approximately eight years old, its dignified medium undermined by the detail that I’m sporting a silly white seventies T-shirt featuring red trim. Furthermore, Eli was occasionally a bit mischievous. He subscribed to Playboy, leaving copies in plain sight of his grandkids. As I’ve also recently learned, slightly to my dismay, he snapped some pin-up shots and nude images of my grandmother Tessie, during her younger years.

Eli Fuchs’s wife, Tessie.

However, it’s his selfies that leave me in awe. This happens to be a significant anniversary for the art form. Fifteen years prior, in June 2010, Apple launched the iPhone 4, the initial model to incorporate a front-facing camera. While mirror images were already in vogue, you could now fine-tune your expression before depressing the button, or tactically situate your device, so it wasn’t obvious that you were the individual capturing the shot. Four months subsequently, in October 2010, a fresh social-media application dubbed Instagram debuted in Apple’s App Store. This bestowed the selfie with a sense of immediacy: your self-portrait could be uploaded in an instant from your gadget to an ever-demanding feed. Should you be a specific kind of personality, possessing a certain measure of influence, it could even be turned into a revenue stream.

For Eli Fuchs, the selfie offered no such immediacy or viewership. The actual procedure entailed an immense amount of effort. In his initial endeavors, you can discern that he employed a mirror to capture his reflection, and he undoubtedly meticulously planned his attempts in accordance with the available light. Afterward, he had to process his film. My mother, presently ninety, recalls that, despite the cramped quarters at home, “he maintained a darkroom equipped with trays containing diverse types of solutions. Subsequently, there was an entire drying setup, with the prints suspended on a line.”

At some juncture, Eli became familiar with the shutter-release cable, empowering him to forgo the mirror and simply aim the device at himself. A short time later, he acquired a 35-mm. camera, signifying that he could shoot outdoors without hauling around his weighty apparatus: the plate camera, the tripod, and the dark fabric he occasionally draped over his head.

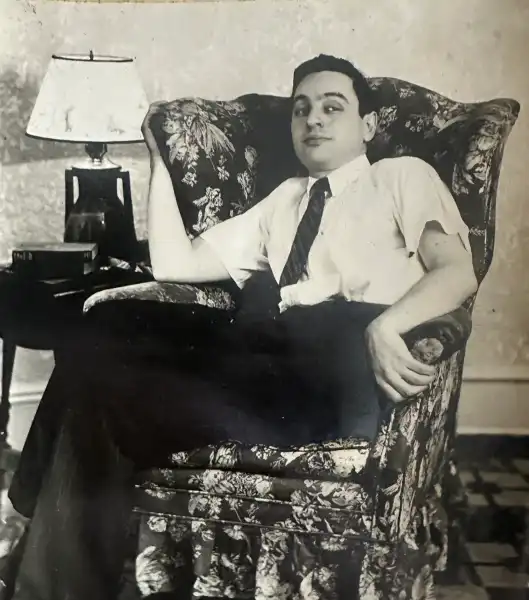

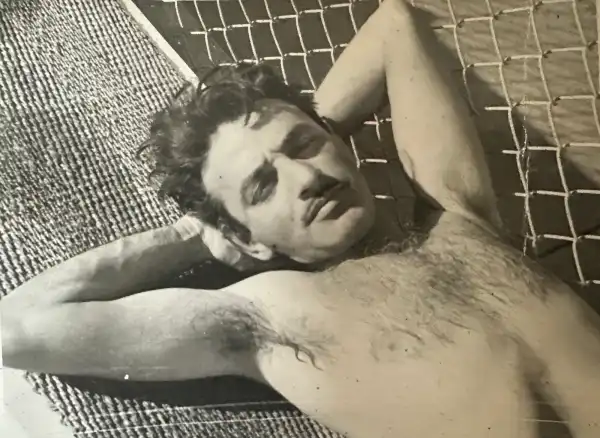

By the nineteen-forties, when he was in his thirties, Eli was evidently more self-assured in his appearance. In snapshots from this time frame, his slender build has broadened, his hair is slicked back, and his mustache resembles the thin, Clark Gable style. The humorous expressions of his early selfies have disappeared. He’s posing in a dreamy manner, shirtless, in a hammock. He’s projecting an elegant image in a peak-lapel suit complemented by a boutonnière. He’s resting an elbow atop a low wall, presenting himself in an “about the author” pose. Occasionally, he employs both the shutter-release cable and a mirror—you can deduce this because, while clutching the cord, he also directs his gaze slightly to the side, to examine his reflection.

In one such cable-and-mirror set of images, he’s smartly attired in a plaid oxford shirt and a tie. He experiments with a knowing smile, followed by a playful wink. Subsequently, the shirt is discarded and the stomach is contracted. As I perused these pictures, I was dumbfounded to realize that he didn’t invariably conduct these shoots in isolation. He sometimes enlisted a small assistant: my five-year-old mom, who, in one photo, is positioned behind him wearing a cap-sleeve dress, a ribbon in her hair, depressing the shutter while he smolders for the mirror, clad only in boxer shorts.

What’s noteworthy about Eli’s selfies is the extent to which they mirror today’s iterations. His objective, at least as far as these photographs were concerned, wasn’t artistic. He didn’t set out to craft a self-portrait reminiscent of Rembrandt or Frida Kahlo. He was certainly capable of such a feat; on my office wall hangs a refined ink-wash self-portrait in which he’s seated at his desk at the Raritan Arsenal, reviewing page layouts while elegantly holding a cigarette. Rather, in his photographic self-portraits, Eli Fuchs was merely a young Brooklyn bloke endeavoring to generate an idealized depiction of himself—to envision himself as a celebrity.

My mother recollects that he felt dissatisfied with his “hook nose.” This descriptor was as laden with significance during that era as it was accurately descriptive. In James T. Farrell’s “Studs Lonigan” trilogy of novels originating from the nineteen-thirties, taking place in Chicago’s Irish American South Side, the rugged figures recurrently allude to Jews as “hooknoses,” not to mention “sheenies,” and, my personal favorite, “noodle-soup drinkers.”

Occasionally, my mom explains, she caught Eli observing himself in the mirror, manipulating his nose in various directions, attempting to digitally enhance his visage in an analog manner. Subsequent to her imparting this information to me, I observed that my grandfather took great care to photograph himself head-on, his chin generally in alignment with the lens. Solely in a handful of images is his head sufficiently rotated to reveal his schnoz in all its Ashkenazic prominence. What was transpiring? Was he endeavoring to separate himself from his progenitors, struggling immigrants originating from Russia? Were his selfies a means of envisioning himself as a “true” American?

Eli passed away in 1977, while I was still a child, precluding me from having the chance to directly question him concerning the photographs. Nevertheless, one of his siblings, Daniel Fuchs, bequeathed some insights. Daniel, three years Eli’s senior, was a novelist and screenwriter whose written works were greatly admired by Irving Howe and John Updike, the latter of whom, in 1971, in this very publication, lauded him as “a poet who never needed to strain for a poetic effect, a magician who rendered magic almost deceptively effortless.” (Daniel also published sixteen short stories in The New Yorker.)

In more recent decades, Daniel has posthumously emerged as a poet of Brooklyn. His renown rests on three social-realist novels depicting Jewish tenement life published during the nineteen-thirties: “Summer in Williamsburg,” “Homage to Blenholt,” and “Low Company.” These books experienced paltry sales upon their initial release but garnered belated acclaim when republished as a trilogy, initially in the sixties and again in the seventies, under the title “The Williamsburg Trilogy.” (We Fuchs-descended pedants emphasize that “Low Company” is in actuality set in Brighton Beach.)

Daniel’s professional misfortune as a novelist induced him to relocate to Los Angeles to venture into screenwriting. He succeeded, although not spectacularly, focusing on crime and heist films and securing an Academy Award for Best Story for “Love Me or Leave Me” (1955), starring Doris Day as the vocalist Ruth Etting and James Cagney as her gangster spouse. During his later years, Daniel published several reflections on Hollywood and the extended journey he’d undertaken from humble Williamsburg. “Within a small radius of my residence, South Second Street between Hooper and Keap, there existed no fewer than seven movie theaters,” he penned in the Times in 1971. “The program was changed either every day or every other day, I can’t recall which, and nearly all of us, born children, regularly frequented the Hooper twice a week, with many of us going even more often.”

It’s this infatuation with movies from his and Eli’s youth that offers insight into my grandfather’s mindset. Daniel, in the Times article, contemplates the notion that “the movies enjoyed their great expansion on account of a serendipitous alignment of timing, occurring precisely when the flood of immigration was at its peak.” However, that wasn’t the genuine allure of the cinema, at least not for the Fuchses. “What these pictures achieved—with their potency and energy, their mastery over life and consistently affirming statements—was to counteract the apprehension that seized and constricted us,” Daniel writes. “It was an indistinct, amorphous dread that descended upon us nearly unconsciously from our parents, a dread born of Old World oppressions, the trials of existence in the New World, and the hardships endured by our parents and grandparents in transferring themselves and their families from the Old World to the New—it was as if the act of immigration had depleted their fortitude and valor.”

Eli Fuchs’s brother Daniel, an Academy Award-winning screenwriter.

Consequently, for someone of Eli’s ilk, projecting movie-star-esque potency and vigor served as an endeavor in social elevation, distancing himself from the somber reality of his babushka-clad predecessors. And the hardships of existence in the New World? The Fuchses were no strangers to adversity. Eli and Daniel were preceded by four brothers. In 1909, mere days after their mother, Sara, gave birth to Daniel, one of these boys, four-year-old George, tragically perished after falling while playing atop the roof of their tenement dwelling on the Lower East Side. The apartment’s situation had furnished my great-grandfather Jacob with a suitably brief commute to his place of work—he managed a newsstand in the lobby of the newly erected Whitehall Building, on Battery Place—however, George’s demise spurred the family’s relocation to Williamsburg, which, despite its chaotic nature, represented an improvement from the perilous slum they’d been residing in.

His birth overshadowed by his family’s most profound misfortune, Daniel discovered solace in films and purposefully transported himself into the fantasy world of Hollywood. On radiant afternoons there, he recounted in 1971, reminiscing about his exhilarating days as a newcomer, he would traverse the Warner Bros. lots, observing “the studio performers in their outfits at their perpetual game.” Eli’s existence, conversely, remained commonplace, that of a career civil servant who transferred his family from scruffy Brooklyn to suburban Highland Park, New Jersey. An inventor at heart, he leased a workspace in New Brunswick, across the Raritan River, wherein, when off duty, he devised mechanisms that he hoped would gain traction and propel him toward greater achievements. One such device replicated a single photograph as a sheet of fifty adhesive stamps bearing the image. He advertised this offering in the rear pages of low-cost publications, under the banner of Stampix. One would forward a photo of, for example, their newborn child, and, in exchange for a dollar and a self-addressed stamped envelope, receive their image back in addition to fifty miniature adhesive portraits suitable for birth announcements.

Stampix fared reasonably well, although not exceptionally; Eli divested the business in 1947. The singular major unforeseen event in his life is that, during the fifties, he took the plunge and corrected his nose. Furthermore, it’s even stranger—he lavished money on rhinoplasty not solely for himself but also for his spouse and daughter.

My then-adolescent mother, whose original nose bore a resemblance to her father’s, hadn’t even communicated an inclination to undergo surgery. She was a scholarly and nature-loving young woman who subsequently became a research scientist at Johnson & Johnson. “My parents were consistently endeavoring to encourage me to be more glamorous, an ambition I didn’t share,” she confided in me. “However, I acquiesced for them, as it brought them joy.”

The Eli I knew was distinguished in appearance, although I regret never having witnessed the nose that so greatly tormented him. It’s peculiar to consider my grandfather, who graciously escorted my siblings and me through the Smithsonian museums and treated us to Baskin-Robbins, as a man possessed by the vanity of a present-day influencer. But the proof resides there, within those stacks of images. He lived a commendable existence, yet his grand ambitions remained dreams, their most complete embodiment captured within the selfies he left as his legacy.

Sourse: newyorker.com