Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

For a few weeks each August, the Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh Festival Fringe fill every theatre, student center, lecture hall, and pub basement in the Scottish capital with performances. Visitors and artists are encouraged to binge in every sense: in just six days, I was able to see twenty-eight shows—I know stronger, better people would have done more—and, while rushing down one picturesque cobblestone lane, I was also able to see three drunk guys barf in perfect Olympic synchrony. (My companion noted, primly, that there was an Oasis concert in town.)

Despite the Dionysian frenzy, which was not merely drunken but often sweet and social, it seemed to me to be a particularly uneasy season. You heard everywhere that the price of temporary housing in Edinburgh had rocketed after Oasis scheduled part of its tour during the first half of the Fringe—for his part, Oasis’s Liam Gallagher described the festival as “people juggling fucking bollocks and that”—and it was hard not to notice that some longtime festival fixtures, like the commissioning producers Paines Plough, had reduced their usually dominating presence to a handful of plays.

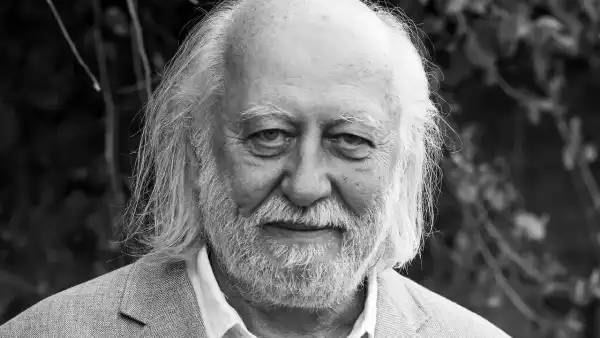

The month’s biggest show—and the marquee offering of the International Festival—is James Graham’s “Make It Happen,” a retelling of the 2008 collapse of the Royal Bank of Scotland, which was briefly the richest bank in the world. Graham positions the bank’s hubristic C.E.O., Fred Goodwin (Sandy Grierson), as a figure from Greek tragedy: a chorus sings slowed-down pop songs whenever he considers a particularly deceptive outlay of funds, and he’s visited by the disapproving ghost of Adam Smith, the Scottish proto-economist and “father of capitalism,” played with desultory humor by Brian Cox. The writing is as bald as a pantomime script—“Your offer document, Fred, is magnificent,” one starstruck employee says—and takes a strangely sentimental stance on the Scottish financier’s guilt. Even after Graham demonstrates the bank’s world-breaking greed, he ends the play with Goodwin looking hopefully out at the horizon, as a chorus member carries a metaphorically freighted sapling (new growth!) onto the stage. Does Goodwin really need this syrupy quasi-redemption? I checked, and he’s still getting a pension from R.B.S. worth six hundred thousand pounds a year.

But, of course, that right there is the point of “Make It Happen”—to make us check, to make us look back. Graham’s play, like many shows in this year’s offerings, functions as both testimonial and memento. In all the recent hubbub around problematic memorials and whether they should stay up or come down, we rarely note that fake Doric columns or big equestrian statues do a crummy job of reminding us about our history. Plays can force you to sit and remember; monuments allow you to walk by and forget.

Many of the finest productions I saw in the Fringe took the position of living memorials to horrors. Sometimes an insistence on accuracy turned these shows into political statements, whether they were originally designed that way or not. The great comedian-activist Mark Thomas, starring as Frankie in Ed Edwards’s solo prison drama “Ordinary Decent Criminal” (one of Paines Plough’s two offerings), did such a fine job of making the case for socialist solidarity with the I.R.A. that the actor broke the fourth wall to rail against the actual Orange Order march by Irish Protestants in the park just outside the venue. “Now back to the script,” Thomas said, after shaking a fist. The comedian Nish Kumar, who delivered a superb, motormouthed roller-coaster of a standup hour called “Nish, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” spent time reminding the audience both of Boris Johnson’s violations of British COVID lockdown law and of the Royal Family’s refusal to repatriate the Koh-i-Noor diamond. (“I didn’t mind the old lady,” he said, referring to the Queen. He clearly has less affection for Charles.)

Niall Moorjani, in their play “Kanpur: 1857,” actually describes an existing monument, one that still stands on the Edinburgh Castle esplanade, erected in honor of the members of the 78th Highland Regiment lost in the so-called Indian Mutiny. But no complete history is written in stone. Moorjani’s character—a rebel tied to a cannon, desperately trying to placate a cheerfully murderous British officer (Jonathan Oldfield)—emphasizes the complexity of accurately telling the story of a war. The rebel describes the massacre of hundreds of British women and children at the hands of the revolutionaries; they also describe the ensuing reprisals by the colonizers against thousands of Indians. Moorjani ends their lyrically written tale about atrocity and asymmetric vengeance with the projection of a few lines by Refaat Al-Areer, a Palestinian poet: “If I must die / let it bring hope / let it be a tale.” Al-Areer was killed by an Israeli air strike in 2023.

A buzz of baffled sorrow, or laughter-in-extremis, underlay almost every production I saw, including several hour-long shows about, variously, sexual assault, state terror, and queer embattlement. The trans performer Chiquitita’s exuberant turn in the sexually frank “Red Ink,” an often hilarious autobiographical one-person work by the activist and sex worker Cecilia Gentili about growing up trans in Argentina, is shadowed by the text’s prescience about Gentili’s early death. My lightest evening ended with “Common Knowledge,” a strange, wistful monologue about raising a nonbinary child by Rosie O’Donnell, who has moved to Ireland to avoid the long arm of Donald Trump and his threats issued via Truth Social. This came up a few times—the sense of U.S. artists being in exile, or being too afraid to go back home.

My favorite work in the look-back-to-look-now vein was Victoria Melody’s “Trouble, Struggle, Bubble and Squeak,” a delightfully oddball solo account of her participation in two apparently very different associations: an English Civil War-reënactment society and the community center at a social housing estate, where residents are sometimes forbidden from controlling their local green spaces. The two strands of her tale come together in her deep interest in the Diggers, the proto-socialist seventeenth-century resistance movement that called the earth a “common treasury” and argued that certain resources should be expropriated by the people. Everywhere she finds wonderful people, everyday heroes, in and out of armor. Melody wears a period-appropriate red woolen musketeer’s outfit, and apologizes for her period-inappropriate water goblet (“I’ve got a tankard coming!”), but the shy, tiny, funny woman is really a radical in elf’s clothing, bearing a new message of utopian rebellion.

The lushest, most physically beautiful offerings were often from countries where government arts funding still meaningfully supports performance. The Brazilian production of Michel Marc Bouchard’s violent pastoral “Tom at the Farm,” directed in mud-covered, extravagantly physical fashion by Rodrigo Portella, transposes the original Canadian setting to a sepia-lit anywhere, where Tom (Armando Babaioff), forcibly re-closeted at his dead partner’s rural home, falls under the hypnotic control of his lover’s brutal brother (Iano Salomão). (Babaioff himself adapted the play, galvanized by the homophobia in his native Brazil.) Perhaps the most stunning production I saw was the wordless physical-theatre piece “Works and Days,” by the Belgian company FC Bergman, in the International Festival. Again, the focus was on earth: the show portrays a collaborative agrarian society (actors literally till the stage as though it were soil, ramming a plow through its boards, then raise a barn together) that eventually welcomes technology in the form of a copper steam engine. Once this clanking god arrives, the members of this society writhe nakedly in its red shadow, but they never collaborate on anything again. Afterward, at the talk-back, the creator-actor Stef Aerts described his theatre group as “romantic nihilists.” Humanity seems to be moving toward its end, Aerts said, but they were content to know that other forms of life would continue without them. Perhaps “Works and Days,” too, was a memorial; this strange, often ecstatic show was like a funeral rite for all of us, just a little ahead of schedule. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com