Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

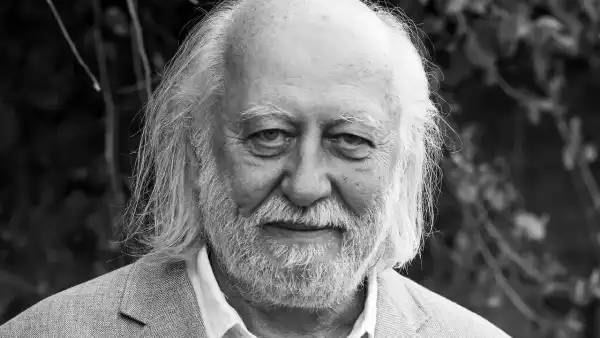

Eddy van Wessel, a Dutch freelance photographer who has covered wars in Chechnya, Iraq, and Syria, arrived in Kyiv in late February, 2022, two days into the Russian invasion. His working method is intuitive, even improvisational. In Ukraine, he drove his own Škoda (later, after he crashed that car into a destroyed Russian tank, he switched to a Subaru) and shot in black-and-white on a forty-year-old camera. That first trip lasted about a month; he’s returned a dozen times since, travelling from Kharkiv to Mykolaiv and the besieged towns and cities of the Donbas, developing an intimacy with the country and its people that, on the page, is both painful and revealing.

In Kharkiv, crawl spaces under the foundations of the city’s Soviet-era buildings have become new homes for large communities.

A rocket launcher in the Donbas.

Chasiv Yar, the medical staging point for fighters in Bakhmut.

In June, van Wessel published “Ukraine,” a photo book collecting nearly two hundred images taken over the course of more than three years—essentially, a visual history of the war. “What I’m trying to capture,” van Wessel told me, “is a personal emotion, what moves me in the moment—clicking the shutter is not a matter of framing or light, but, rather, you could say, a decision of the heart.” A woman and her dog look out, with stoicism and dignity, from a car pockmarked by bullets; a wounded soldier teeters on the edge of collapse. Most of the photographs in “Ukraine” were taken on the edges of violence; they are not gory and never prurient, but instead are laced with a sense of what van Wessel called “the place where life and death touch each other.”

A woman and her dog wait in their bullet-riddled car at a military checkpoint.

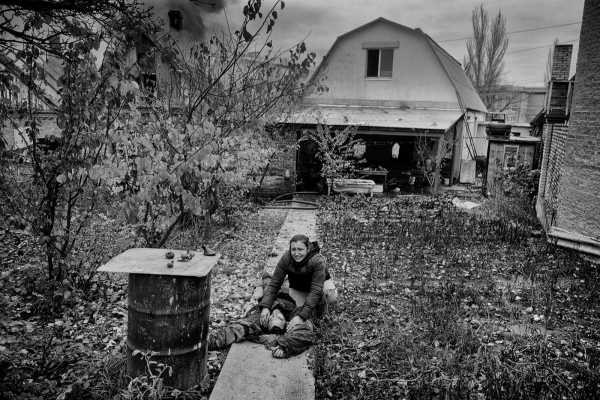

A particularly wrenching picture from Bakhmut was taken in 2023, when the city was under siege by Russian forces and mostly abandoned. Van Wessel lived with a brigade of local firefighters—“the only ones left,” he said. A call came in reporting that a house had been hit by Russian artillery shelling. The firefighters sped over in their Soviet-era fire truck; van Wessel followed in his Subaru. When he arrived, he saw that the firefighters had pulled the body of a dead man from the house and brought it to the garden. He knew the scene required a picture, and began to pace around, sizing up the right way to take the shot. “I know it sounds strange,” he told me, “but I was looking for an angle. You want to be respectful. You don’t want to make people look awful, even if they’re already dead.” He heard a terrible, piercing shriek. The man’s wife had been out searching for groceries and returned to the ghoulish scene. She ran through the house and out into the garden, throwing herself at her husband’s body. In van Wessel’s photograph, the man is prone on a cement pathway. His wife is resting her hands on his shoulders, with her head turned upward, a gesture of impotent torment.

A woman with the body of her husband after firefighters pulled him out of a burning house in Bakhmut, in 2023.

War reveals a number of terrible truths in extremis: life is fragile; its end is often random, pointless; and the line separating the two realms is both closer and thinner than we usually allow ourselves to perceive. In Ukraine, by this point in the war, death is omnipresent—“one or two handshakes away,” as a friend of mine in Kyiv once put it. Van Wessel captures how something can be at once utterly horrible, an emotional devastation for which no one is prepared, and also grimly routine.

A mobile-phone advertisement in Orikhiv.

The Irpin Bridge, like much of the infrastructure in the Ukraine, has been destroyed by Russian bombing.

In June, 2023, a Russian Iskander ballistic missile blew apart Ria Lounge, a popular pizza restaurant (and one of the few that remained open) in Kramatorsk, a city in the Donbas that was fifteen miles from the front at the time. Thirteen people were killed, among them Victoria Amelina, a Ukrainian writer, and two fourteen-year-old twins, Yuliya and Anna Aksenchenko. The girls had lived with their parents in Kramatorsk, but the war prompted the family to move to a smaller village an hour’s drive away, in the hope that it would be safer. Still, their mother kept her job at Kramatorsk’s municipal hospital, and that day Yuliya and Anna came to visit her at work. Afterward, they decided to have a pizza. Van Wessel was in Kramatorsk when the attack happened and showed up at the restaurant, camera in hand, a half hour after the strike.

But those pictures aren’t in the book. Instead, there is an image of Yuliya and Anna’s funeral, three days later. Van Wessel followed the hearse with their bodies as it drove out to the village where the family had been living, and where the girls would be buried. A man came up to van Wessel and asked him to keep his distance. That seemed reasonable: the intensity of the grief was enveloping, a veil of sorrow that van Wessel, a father to twins himself, was loath to make worse with his own presence. Later, a different man approached him and made another request: it would be appreciated if, after the funeral, van Wessel paid his respects to the family. He took that as a signal; he moved a few steps closer. The mourners seemed to no longer notice him.

The funeral of the twins Yuliya and Anna, aged fourteen.

Van Wessel’s picture is of two teen-age friends of Yuliya and Anna’s, clutching each other, or maybe holding each other up, their eyes closed, clearly sobbing, standing over an open casket. The body of one of the girls is covered in a shroud made of satin and lace. The girls’ mother, van Wessel told me, crumpled to the ground next to the grave sites, and had to be carried away from the scene. “I had the feeling three lives had ended,” he said.

In other wars, van Wessel observed how quickly both state and society effectively collapsed. Basic services disappeared; individuals were left to fend for themselves. He is not unduly sentimental about Ukraine’s resilience—a widely popularized notion that captures a fundamental dynamic of the war but which also risks masking the human messiness and imperfection that remains. Rather, he portrays the country and its people as they are: dignified but fragile, not heroic or uniquely saintly, but resolved to withstand the unthinkable, certain that there is no other choice.

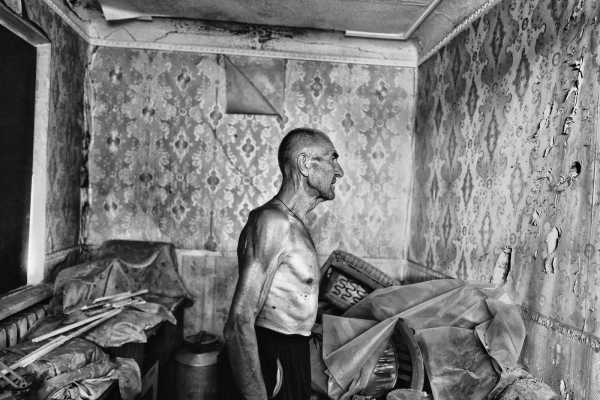

Oleksandr Kurinnyi, a sixty-six-year-old welder from Siversk, in the room where his wife was killed by a Russian missile.

Burned-out houses in Kharkiv after Russian bombardments.

A photograph taken in Kharkiv shows a man standing atop a pile of smoldering rubble, aiming a thin stream of water from a garden hose at a cloud of smoke where his home once stood. “I couldn’t understand what he was doing,” van Wessel told me. “Was it a symbolic gesture? Was it his way to fight the demons that had come and taken everything from him?” Or, as he came to understand it, the man was acting out an impulse that van Wessel saw repeated often across Ukraine. “People tend to want things as they were,” he said. “We want to tell ourselves that there’s always something worth saving, that some foundation remains, even when there’s nothing left at all.”

Residents in Irpin, a suburb of Kyiv, in 2023.

A nine-year-old boy on the doorstep of his home in Irpin, in 2023.

That photograph comes in the middle of the book, a stretch of forty or so pages of images taken on a Widelux, a panoramic film camera that dates to the nineteen-fifties. Van Wessel chose to have these pictures fold in on themselves, with some running over to the following pages, creating the effect of a disorienting scroll without beginning or end. “I wanted to capture some of the frustration and insecurity people in Ukraine feel,” he said. “You can’t see the pictures in full. You’re annoyed, you have to work for it, roll the book around. Maybe you’re even alarmed: you don’t know what the next moment holds, the next obstacle you’ll face.”

A man drags some food toward his shelter in Vuhledar, in the Donbas. When van Wessel asked to take his portrait, the man said, “Please, no! I don’t want my children to see me like this.”

Sourse: newyorker.com