Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Florence Mars was born on New Year’s Day, 1923, in Neshoba County, Mississippi, a remote patch in the center of the state, where red clay makes it difficult to farm row crops. The Mars family dealt in timber, cattle, medicine, and the law. They lived in Philadelphia, the county seat, which was chartered near a Choctaw sacred mound not long after the tribe, in 1830, ceded more than ten million acres to white settlers under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

Small and observant, Mars lived with her parents and extended kin in a Victorian house with a library and a piano, around which the family gathered to sing show tunes. The Marses were educated and intellectually curious, and questions were encouraged. As a child, Mars returned home from the Chicago World’s Fair and, having just seen a display of dinosaur fossils, contested the doctrine that Earth is four thousand years old. A child in another type of family might have been punished for that stance, assuming she’d had the opportunity to see a World’s Fair at all.

“What is this business with the Negro?” Mars once asked her grandfather, whom she called Poppaw. In a memoir, she recalled him answering, “They’ve been treated mighty bad.” Poppaw never minded sharing his opinions. He held in particularly low esteem the types of white people who chose not to educate their children, and “had no community ties and usually no church affiliation,” and were “sullen and standoffish,” “unreliable,” and “too sorry to plant a garden.” Such people, Mars wrote, “settled their differences with fists or firearms.” At some point, Mars learned that her maternal great-grandfather had fathered Black children, but it’s unclear whether, or how well, she knew what the Stanford historian James T. Campbell has described as her family’s “assortment of black cousins.”

Saturday shoppers, downtown Philadelphia.

After briefly attending Millsaps, a private Methodist college in Jackson, Mars transferred to the University of Mississippi, her father’s law-school alma mater, with her best friend, Betty Bobo. When Bobo and Mars advocated on behalf of Black laundry workers on strike, the employees’ white manager was said to have asked them, “What Northern Communist newspaper do you represent?” Mars graduated in 1944 and moved to Atlanta, where she spent eighteen months working for Delta, helping to transport troops fighting in the Second World War. Afterward, she lived mostly in New Orleans, several hours south of Neshoba County. She befriended writers and artists, entered psychotherapy, got into jazz, began painting.

In 1950, Poppaw, one of Neshoba’s largest landowners, died and left his estate to Mars, whose father had died of alcohol poisoning when she was a child. Mars used the inheritance to raise purebred Hereford cattle and to buy a stockyard. She had just entered her thirties when, on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board of Education, declared public-school segregation unconstitutional and, soon after, ordered states to integrate “with all deliberate speed.” One of Mississippi’s congressmen, John Bell Williams, called May 17th “Black Monday.” Senator James O. Eastland accused the Supreme Court of having been “indoctrinated and brainwashed by left-wing pressure groups.”

White supremacy had been enshrined in Mississippi’s state constitution since 1890. The Black vote was suppressed in a variety of ways—lynching, poll taxes, literacy tests. Black registrants were expected to satisfactorily explain, in writing, the concept of habeas corpus, or to answer ludicrous questions, such as “How many bubbles in a bar of soap?” In the Delta city of Indianola, business and civic leaders established the first White Citizens’ Council, which opposed integration through economic terrorism: members could get Black people who tried to vote fired, or worse. “Virtually everyone” who was invited to join the council in Neshoba County did so, Mars wrote: “Refusal would have been seen as an act of traitorous disloyalty to Mississippi and to the South.”

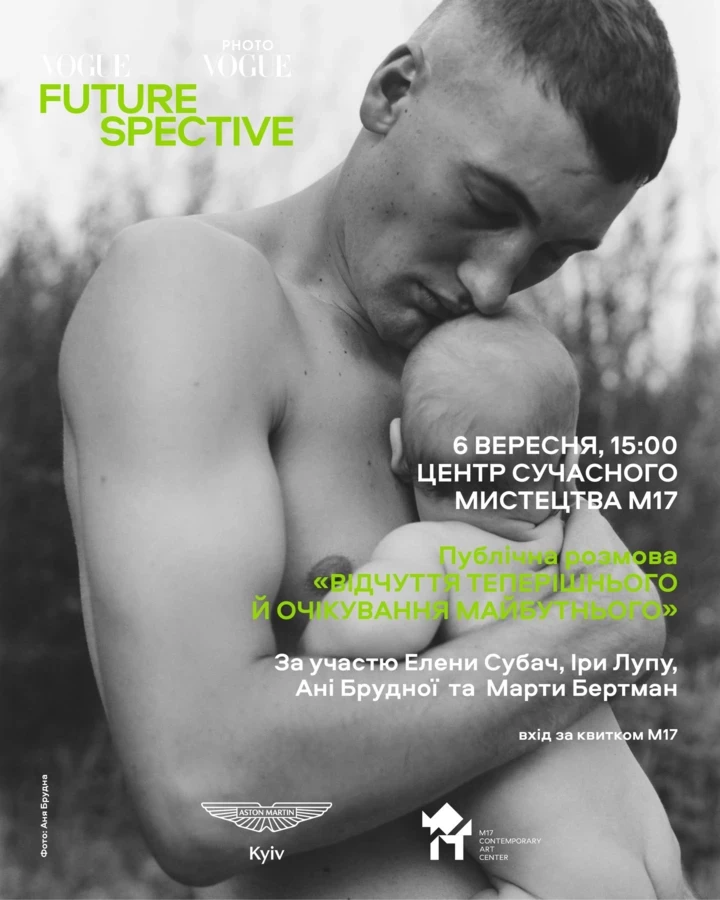

Meanwhile, Mars had moved on from painting to photography. “Because I knew the street scenes of Philadelphia would soon begin to change,” she wrote, “I bought a camera and an enlarger, built a darkroom, and began to snap thousands of pictures.”

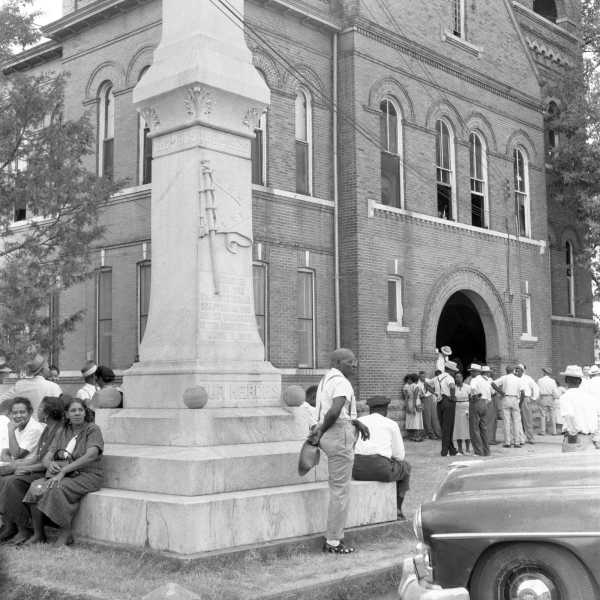

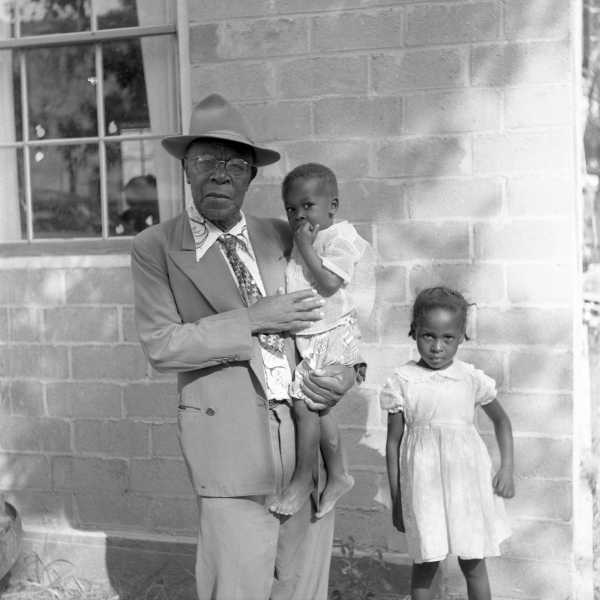

Mars shot in black-and-white, with a Graflex 22. She found many of her subjects, most of whom were Black, outdoors—sitting on a wooden bench, stirring the contents of a cast-iron pot. She captured residents of Neshoba County in their church clothes, wearing aprons over housedresses, blazers over overalls; battered shoes; bare feet. The scent of seared dust almost rises off her photographs. A small child at a fish fry stands next to an open sack of Mahatma rice. White boys climb the town square’s Confederate monument. Most of Mars’s subjects stare straight into her lens.

Rendering lard.

Fish fry.

Unidentified and undated, Philadelphia.

Gertrude Williams, a Black former bootlegger who had never been taught to read, sometimes accompanied Mars on her photographic excursions, providing “access to arenas of black experience that few white photographers ever saw,” Campbell, the Stanford historian, writes in “Mississippi Witness,” a collection of Mars’s photographs, published in 2019. Campbell and his collaborator, Elaine Owens, raise comparisons to the documentary photography of the New Deal era, particularly the photographs of the novelist Eudora Welty, who shot for the Works Progress Administration. (Mars likely wouldn’t have seen Welty’s photos, which weren’t widely known until 1989.) Although Welty and Mars were both single and white and “lived at once inside and outside the confines of a conservative, racist, patriarchal society,” Campbell writes, Welty’s photos “bespeak a certain political innocence.” Mars, on the other hand, was directly responding to a metastasizing political cruelty—the backlash to Brown. Eastland, the senator, had told Mississippians that they were “obligated to defy” the Supreme Court’s ruling.

In 1955, Mars entered a photo-essay contest put on by Life magazine. She titled her submission “Dignity of Man,” subtitled “The Story of the Southern Negro: Who he Is; What he Is; What he Stands to Lose Through Integration.” Stands to lose? Mars fully supported integration, though she worried that white society would “force the Black Man into oblivion,” or to commit a form of “racial suicide.” Black Americans had survived monstrous injustices with “dignity and poise,” she wrote, arguing that these traits, and so many others, were worth preserving, and emulating. Of “the White Man,” she asked, “What does he fear?” and “Why is he not secure?” (Mars lost the contest.)

That August, two hours northwest of Philadelphia, in the Mississippi Delta county of Leflore, a Black fourteen-year-old from Chicago, Emmett Till, was visiting family. At a country store in Money, he whistled at Carolyn Bryant, the woman who owned the business with her husband, Roy. When Roy found out about this, he and his half brother, J. W. Milam, dragged Till out of bed in the middle of the night and drove him to another relative’s property, where they tortured and killed him. Using barbed wire, they tied a seventy-five-pound fan from a cotton gin to the child’s neck, then dumped his body in the Tallahatchie River. The sight of Till’s mutilated and decomposed corpse at his open-casket funeral galvanized the civil-rights movement.

Carolyn Bryant and her husband, Roy, one of Emmett Till’s killers, inside the courtroom.

Jurors during a recess at the trial.

Mars and her old friend Betty Bobo, whose last name was now Pearson, attended the murder trial of Bryant and Milam. On their way into the courtroom, the women ignored a man who warned them, “You will be hearing things that no white lady should hear.” Mars took a chilling photo of Carolyn Bryant, a thin, pale brunette with dark lipstick and sharp eyebrows, sitting cross-armed in the gallery, looking smug. Another photo shows a Black man standing, Campbell writes, “next to a Confederate monument embossed with the words ‘Our Heroes,’ waiting for the jury to deliver its verdict, waiting to see whether white Mississippians, in their descent into racial madness, had come to abide the slaughter of children.”

The men were acquitted by an all-white, all-male jury, and later admitted—and publicly bragged about—what they had done to Till. Others had been involved, too, the F.B.I. found, but no one was ever held accountable. Carolyn Bryant remarried, taking the last name Donham. Recent attempts to have her indicted failed, and she died last year, in Louisiana, at the age of eighty-eight. In an unpublished memoir about Till’s murder, Donham portrays herself as a victim: “Those terrible days scarred me, and it was hard to heal.”

Outside the courthouse.

In the early sixties, Mars was more or less living in Philadelphia full time but took a months-long vacation to Europe. “I learned, for one thing, how Nazi Germany is possible in a ‘law-abiding Christian society,’ ” she later wrote. Organized religion had never appealed to her—“I found the attitudes of self-righteous church members hypocritical”—but she admired her family’s church for its opposition to post-Brown attempts to close the public schools rather than adhere to federal law. She began teaching a women’s Sunday-school class and singing in the choir.

By the summer of 1964, an election year, Mars was in her early forties. Freedom Summer—an enormous effort to register Black voters—was ongoing in Mississippi. On May 31st, James Chaney, a Black organizer from nearby Meridian, and Michael Schwerner, a white civil-rights worker from New York City, held a community meeting at Mount Zion, a Black church in Neshoba County. On June 16th, Mount Zion was burned to the ground. Three days later, the Senate passed the Civil Rights Act.

A new faction of the Ku Klux Klan, the White Knights, had just been formed in Mississippi. Mars wrote that the White Knights’ leader had taken note of Schwerner, whom he characterized as “a thorn in the side of everyone living, especially the white people.” It was later thought that the Klan targeted Mount Zion in order to lure Schwerner back to Neshoba County, to be “taken care of.” (Schwerner had already dodged one assassination attempt when his wife, Rita, declined to open her door to a Klansman posing as a vacuum-cleaner salesman.)

Five days after the fire, Schwerner did return to Neshoba County, along with Chaney and another white civil-rights worker from New York, Andrew Goodman, to investigate. They were driving Schwerner’s station wagon. When they failed to return to their headquarters, in Meridian, a colleague reported them missing. Locals declared the case a “hoax” perpetrated by civil-rights leaders to trigger an “invasion” of federal agents.

The F.B.I. arrived en masse, along with sailors from a naval airbase. They found the station wagon empty and torched. After six weeks of searching, and using a tip from a confidential informant, the men’s bodies were found buried in an earthen dam, near where Mississippi’s power brokers were about to gather for the annual Neshoba County Fair. Investigators determined that Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman had been shot, but locals went on abiding conspiracy theories, suggesting that the murders had been carried out by the civil-rights movement, to make Mississippi look bad.

The state declined to prosecute anyone. The Justice Department used Reconstruction-era statutes to charge eighteen men with having deprived the victims of their civil rights, which, as one reporter later wrote in the Oxford American, was “as close to a murder trial as you were apt to get in the 1960s South when few juries were willing to prosecute a white person for any crime against a black man, much less the crime of murder.” The defendants included the sheriff, the deputy sheriff, and other members of law enforcement. Seven were convicted.

A banker, a college president, a newspaper publisher, and a financier at the Neshoba County Fair.

Mars had recoiled from the “furious conformity” that enveloped Neshoba County during the investigation. “Only a tiny handful among white townspeople spoke out, braving social ostracism and threats of violence to denounce the murders and decry the climate of fear and intimidation that had overtaken their community,” Campbell writes. “Few did so more openly and courageously than Florence Mars.” Mars visited the civil-rights workers’ office in Meridian, coöperated with the F.B.I., and agreed to testify before a federal grand jury about past treatment of Black people at the hands of violent local authorities. She launched a fund-raiser to help rebuild Mount Zion, and tried to start a “Philadelphia-to-Philadelphia” youth exchange, which would link her home town to the city in Pennsylvania.

She was labelled a snitch and a spy. Local law-enforcement officers surveilled her; anonymous callers threatened her. The sheriff threw her in the “drunk tank,” which Campbell describes as “an act that scandalized some townspeople more than the murders themselves.” Mars’s church forced her out of her teaching positions—the white congregation disapproved of her “dangerous beliefs.” The Klan organized a boycott of her stockyard, forcing the business to close.

After 1964, Mars largely stopped taking photos but remained obsessed with the murders. Campbell notes that she appeared to be asking herself, “How do ordinary people become complicit in grave injustice? And how, in such fevered circumstances, do a few people find the courage to resist, to recognize evil and call it by its name?” On the second anniversary of the killings, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., and other civil-rights leaders marched in Philadelphia’s town square, where they were confronted by a white mob. “King later described the episode as one of the two most terrifying experiences of his life,” Campbell writes, adding that King understandably may have missed the sight of “the small woman standing silently on the square’s elevated sidewalk, holding aloft an American flag in greeting.”

Confederate monument, Philadelphia town square.

In 1867, two years after the end of the Civil War, about sixty-seven per cent of eligible Black Mississippians were registered to vote. Between then and 1876, at least two hundred and twenty-six Black residents were elected to office, including state senators and a lieutenant governor. “For a limited time, black Mississippians were able to engage in the government and shape political outcomes,” the University of Mississippi’s branch of the Andrew Goodman Foundation, which focusses on civil rights and voting, has noted.

Once federal troops left the South, influential white Mississippians, realizing that they were outnumbered by freedmen, got busy intimidating, killing, gerrymandering, and otherwise cheating their way back to absolute power. J. B. Chrisman, a judge who had participated in the state’s constitutional convention of 1890, declared that it was “no secret that there has not been a full vote and a fair count in Mississippi since 1875—that we have been preserving the ascendency of the white people by revolutionary methods. In plain words, we have been stuffing ballot-boxes, committing perjury and here and there in the state carrying the elections by fraud and violence.” By the sixties, as few as six per cent of the state’s eligible Black voters were registered.

A man and his grandchildren, outside Sipsey Church.

Half a century later, the number has rebounded to more than seventy-two per cent. Still, turnout remains low in Mississippi, which, according to the Center for Public Integrity, “has rejected most of the policies known to level the playing field of voting access to lower-income voters and people of color.” Mississippi doesn’t offer early voting or online voter registration, and it imposes a lifetime voting ban on people found guilty of a number of felonies, a policy that disproportionately disenfranchises Black voters. Mississippi has more Black elected officials than any other state, but most hold local office—the state has never elected a Black governor, and only five Black candidates have made it to Congress, despite the fact that Mississippi has the highest percentage of Black residents of any state in the country. For more than thirty years, the governor has designated April as Confederate Heritage Month.

Mars’s memoir, “Witness in Philadelphia,” was published in 1977, and focussed on the killing of Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman. It never found a wide audience but sold well at the bookstore on the Philadelphia town square. “Mars was particularly gratified by the interest of young people, many of whom had heard little or nothing about the murders or their aftermath from their parents,” Campbell writes. Generations of Mississippi textbooks glorified the Lost Cause and omitted mention of civil-rights heroes. In those books, Klansmen were the “patriots.”

Mars died in the spring of 2006, at the age of eighty-three, in Philadelphia. She did not live to see Mississippians make one positive but superficial change: in 2020, they voted to replace the old state flag, which included the Confederate flag, with one that features a magnolia. Nor did Mars live to see the publication of more than one or two of her photos. On Campbell and Owens’s request, the proceeds from “Mississippi Witness” go to the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, in Jackson.

My favorite portrait in the book shows a woman in a polka-dot dress and an apron. Substantial and unsmiling, she stands directly in front of Mars, facing the sun, hands on hips, shoulders squared. Self-help types sometimes counsel us women to privately strike that Wonder Woman pose before we have to do or say something that requires courage. The woman in the photo did it naturally. Behind her, you can almost make out the shadow of Mars, her camera raised.

Mars submitted this undated and unidentified photo to Life, captioned “I done my do.”

Sourse: newyorker.com