Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

MOMA’s new show “Artist’s Choice: Grace Wales Bonner—Spirit Movers” includes thirty-seven objects from the museum’s collection, many of them no larger than a sheet of typing paper. Yet the effect of the exhibition is hardly minimal—not when its centerpiece is Terry Adkins’s soaring, magnificent sculptural ensemble “Last Trumpet.” Set against the gallery’s back wall, the piece lines up four eighteen-foot-long brass horns that reach nearly to the ceiling, as if ready for a celestial choir. It’s one of many musical elements in a show that Wales Bonner, a fashion designer with a curatorial bent, calls “an archive of soulful expression.” A more expansive view of that archive is available in “Dream in the Rhythm,” a book that accompanies the show. Together, the exhibition and the book are the product of a sensibility that’s both sophisticated and intuitive, making connections across periods, mediums, and styles which are so unexpected that every object seems new. Born and based in London, Wales Bonner is the first person in her field who’s been invited by MOMA to organize an “Artist’s Choice” exhibition. In a sense, finding new ways to rework familiar materials is a big part of Wales Bonner’s job in fashion. Still, the wit and intelligence she brings to curation never comes across as an extension of her brand.

W. Eugene Smith, “Rahsaan Roland Kirk,” 1964.Photograph by W. Eugene Smith / Courtesy MOMA

Michelle Kuo, the MOMA curator who oversaw the Wales Bonner project, has described it as “a deeply personal meditation on and around modern Black expression.” “Around” is the key word here. “Spirit Movers” is not a show of Black artists alone. Among the works drawn from MOMA’s permanent collection are lithographs by Jean Dubuffet, sculptures by Jean Arp, books by Richard Long and James Castle, a ring by Alexander Calder, and a fetish object by Lucas Samaras that began as a book but is now covered with pins and armed with a knife, open scissors, a shard of glass, and a razor blade. But the exhibition’s nimble braininess isn’t the result of some academic exercise, and neither the show nor the book strains to make cross-cultural and aesthetic connections. Her juxtaposition of Man Ray’s “Emak Bakia”—a sculpture sporting the polished wood fingerboard of a cello like an elegant erection—and Bill Traylor’s drawing of a man flipping over in ecstasy, feels at once surprising and inevitable.

Man Ray, “Emak Bakia,” 1962, a replica of the original from 1926 (center, in niche, installation view).Photograph courtesy MOMA

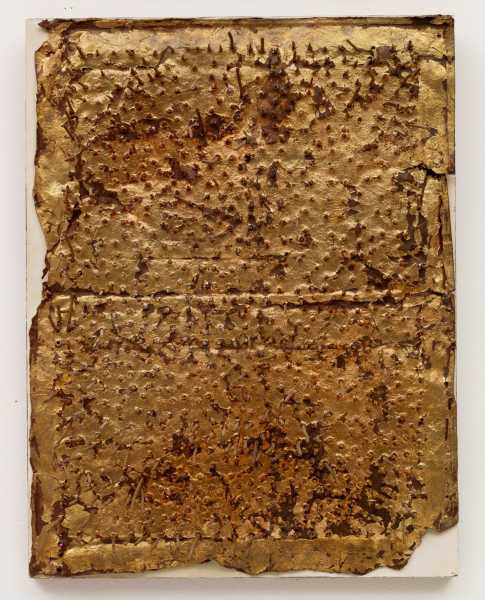

With Adkins’s horns presiding, the conversations that Wales Bonner sets up are both visual and aural, featuring several eccentric avant-garde scores. The installation itself suggests the undulating wave of symphonic notation, with one wall’s arrangement set off by another Adkins work: a well-used drum skin that is burnished gold on one side and stretched across a metal rim hung high, like a slice of the sun. Nearly all the elements in the spare, looping display are abstract, reducing the human body to a gesture, a memory, a presence more spiritual than physical. For a fashion designer, this avoidance of the corporeal seems a bit perverse, but Wales Bonner takes the viewer into account and includes works—like that alarming Samaras—that excite a physical response. Especially tactile and tantalizing are Lenore Tawney’s circle of tiny seeds on open book pages, Mathias Goeritz’s foil-covered wood panel bristling with bent nails, and a scroll by David Hammons, previously unexhibited by MOMA, torn open to reveal a lattice of wire mesh stuffed with tufts of hair gathered from Black barbershops. Standing sentinel in the center of the gallery is “Lady with a Long Neck,” by the Senegalese sculptor Moustapha Dimé, another work from the collection that has never before been on view. Its spine, a roughly chopped tree trunk originally used as a butcher’s block, is partly wrapped in a sheet of corroded iron that suggests a lady’s windswept hair or a shroud closing in.

Moustapha Dimé, “Lady with a Long Neck,” 1992.Photograph courtesy MOMA

Mathias Goeritz, “Message Number 7B, Ecclesiastes VII: 6,” 1959.Photograph courtesy MOMA

Lucas Samaras, “Book 4,” 1962 (installation view).Photo courtesy MOMA

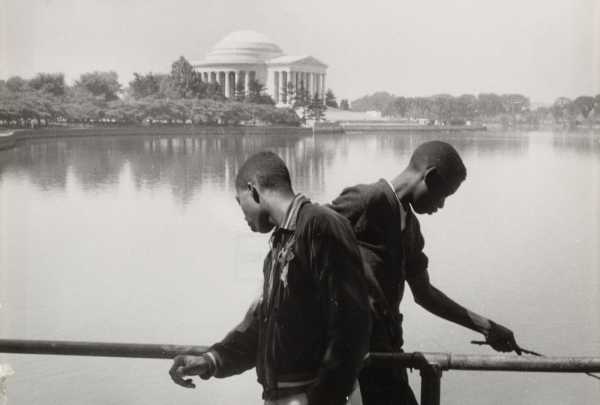

There are only two photographs in “Spirit Movers,” both black-and-white prints, one blown up and displayed on a wall introducing the show. But photographic images dominate the book, making the volume not just a footnote to the exhibition but an essential continuation of the conversation begun there. With work by Dawoud Bey, Lorna Simpson, Roy DeCarava, Ming Smith, and Anthony Barboza, music and movement remain the inspirations. The book’s title comes from the Kenyan novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who describes a character spontaneously picking up a horn and dancing, as onlookers observe: “You did not have to learn. No. You just gave yourself to the dream in the rhythm.” Like the show, the book is characterized by elegant restraint, so any dream of abandon is left to the reader’s imagination. The book incorporates poetry and other texts that expand on the theme of Black expressiveness, including work by Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, Langston Hughes, June Jordan, and Ishmael Reed. “I hear an enthralling symphony,” Wales Bonner writes, “a call to leap into this wider consciousness.” With the insinuating power of a dream, she leads the way. ♦

Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Washington, D.C.,” 1957.Photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum / Courtesy MOMA

Sourse: newyorker.com