Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

After dementia came for my father—after he could no longer read, after he had lost his table manners, after he had started to run his fingers through his hair, as though plagued by an ungraspable thought—I began to consider whether death could sometimes be a mercy. There were so many small moments of grief: when he stuffed his glasses into his mouth, or dismantled his hearing aids, or became too agitated to sit through Thanksgiving dinner. My father was an attorney who’d once won a Supreme Court case, but when I told him, “Dad, you were a lawyer!” he looked impressed and replied, “Really?”

During one period, he would shout “Slivovitz,” the name of a plum schnapps that I can’t recall him ever drinking, and then nearly bust a gut laughing. Sometimes, when we both needed to smile, I would turn to him, poker-faced, and say, “Hey, Dad. Slivovitz!” It worked every time. I imagined the word contained a memory, maybe something about his own father, though he could never say what it was, and, for some reason, I never thought of offering him a shot. A year after his death, I still occasionally holler “Slivovitz” in his honor.

Even as details of my father’s life slipped away from him, and his speech became more garbled or nonsensical, he could always summon every lyric to his favorite old-school tunes—“Bicycle Built for Two,” “Give My Regards to Broadway”—and sing them on pitch. It was like a magic trick: for the duration of “Please don’t take my sunshine away,” he was back—happy, calm, and conversant—and might stay that way for hours.

On a bad day, when he was ninety-five, I watched as he tore paper napkins into ever-tinier shreds, periodically moaning, “I want to go home! I want to go home!” I wasn’t sure where—or when—home was. Those were not questions that he could answer.

That night, feeling despondent, I asked my oldest brother, David, “What kind of quality of life does he have?”

David was quiet for a moment. “I know what you mean,” he finally said. “But then, the other day, I brought him a hot dog and he enjoyed it so much. He kept saying, ‘Mmm-mmm! Boy, this is good!’ He was smiling and laughing and talking. It was like it snapped him back to himself.”

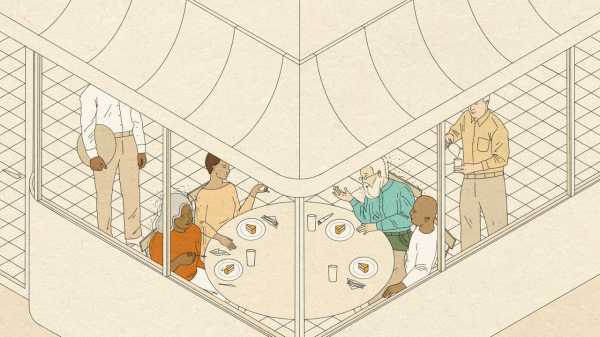

I thought of our conversation when, earlier this summer, I heard that Jake Broder, a playwright and actor who most recently appeared in “The Patient,” was organizing a curious kind of recurring meal with the help of the Global Brain Health Institute, which conducts dementia research. Broder, a fellow at the University of California, San Francisco, campus of the institute, would interview four people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment, drawing out the story of a food that they remembered fondly. He would then work with Gloria Aguirre, the institute’s community-engagement manager, to help them re-create the dishes. Finally, participants would recount their tales to an audience of friends and staff members as they all shared the food. The larger goal of the Dinner Party, as Broder calls the event, was to explore the power of food in triggering memories, improving quality of life, and enhancing neuroplasticity—things that are difficult to achieve with medicines.

On the day before the inaugural Dinner Party, I visited the Adult Day Health Center in the historically Black neighborhood of Bayview, San Francisco, where the gathering would take place. In a nondescript room, twenty-five or so regulars ate nutritious, if uninspired, meals from cardboard trays. In the back kitchen, however, the preparations for tomorrow’s feast had begun. A man named Michael, who wore a Darth Vader baseball cap because he looked a little like the actor James Earl Jones, was holding forth from his wheelchair on the correct way to marinate twenty-six Cornish game hens. (It involved Grand Marnier and lemon juice.) Broder and Aguirre were there, too, squeezing citrus and sprinkling garlic powder between crisp outbursts of “Yes, Chef!”

Like many of the center’s clients, Michael was referred here by his medical team in the hope that it would deepen his connection to others and prevent him from becoming homebound. I was surprised to learn from the staff that, before being tapped to contribute to the Dinner Party, Michael was not especially talkative, sometimes napped in his wheelchair, and had never mentioned a career in restaurants. Now he reeled off stories about his father, a chef for the Southern Pacific Railroad who had taught Michael his trade and “cooked for the President of the United States.” Michael can’t recall which President that might have been, but his father, he said, “was the only one who would cook for him—he wouldn’t let no one else!” The Cornish hens would be tomorrow’s entrée. The rest of the menu included appetizers of potato salad, hot links, and gumbo; and a dessert of lemon-curd pie. (It seems that no one chose vegetables as their Proustian madeleine.)

Research suggests that creative activities, such as drawing or dancing, can reduce anxiety, depression, and agitation in dementia patients; by contributing to the formation of new neural pathways, they may also help slow the progress of Alzheimer’s. Musical memory, in particular, appears to be independent of the regions of the brain that dementia afflicts first—which is probably why my own father could sing even when he struggled to speak. There’s something intuitive about the idea that a beloved food, something as simple as a hot dog, could have a similar animating effect—perhaps activating dormant neurons, or providing a tether of continuity to one’s past.

Broder, who had been stress-chewing a stick of gum as he sous-chefed, excused himself from the kitchen to meet with a slightly built woman with a pixie haircut. Miss Peche, as she introduced herself, had chosen the lemon-curd pie, recalling how her mother would serve her an after-school slice with a tall, cold glass of milk. She never got the recipe but had been working to duplicate it with the sister of one of the center’s staff. “What I loved yesterday,” Broder told her, “was how you talked about that feeling of sweetness—not only the sweetness of the pie but the sweetness of feeling loved when you were eating it.”

“I was!” Miss Peche said. “My parents gave me everything. I was a picky, picky child.”

Broder told Miss Peche that he would summarize her main points on a notecard, the closest that the Dinner Party would have to a script. At first, Miss Peche resisted, wanting to freestyle, but with a little nudging she agreed. “My biggest thing is that I’ll enjoy that pie,” she said. “And I will tell you how it tastes!”

By noon the next day, the center’s main room had been transformed: the laminate tables were covered with silver-speckled paper tablecloths, plastic flatware was rolled in matching napkins, and there were plastic cups with silvery rims. In place of the usual soul-music playlist—Al Green, James Brown, Tower of Power—the instrumental intro of the Temptations’ “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” played on repeat, building anticipation. Four volunteers from the institute would wait tables for forty-odd attendees—clients of the center, plus a few researchers and clinicians, who were eager to see patients away from the formality of a medical office.

When the Dinner Party finally began, closer to lunch than supper, Cheryl, who was in her early seventies, stood first, to wild applause. She clutched a notecard and looked resplendent in sequined leggings, turquoise hoop earrings, and fluffy sandals. In the heat of the moment, she forgot to mention what potato salad meant to her—her mom filled sandwiches with it on Sundays, to eat on the way to church—but she reminisced about the barbeque pit that she and her late husband once owned, not far from where we were sitting. Hot links were a house specialty. She’d passed the recipe on to her son, who owns a food truck, and he’d provided today’s batch.

The next course, gumbo, posed a problem: the woman who was supposed to introduce it, Laura, was nowhere to be found. Broder had to stand up and explain that, at the last minute, her brother had taken her to Sacramento to visit a relative. Instead, Broder projected a video of his interviews with her on a screen. Laura, one of the few white women at the center, had salt-and-pepper hair and dark-lined eyes beneath tortoiseshell glasses. In the video, she explained that gumbo was actually a more recent memory: her best friend at the center, whom she called Niecey, had introduced it to her. It was something special that they liked to share, until Niecey grew too sick to eat it. Laura gave it up, too, in a gesture of solidarity.

The gumbo came around, as rich and peppery and earthy as anyone could want. Then Chef Michael, as he was known now, rose to whoops of excitement. He talked for a while about his father’s career and his own.

“A good meal is intimacy and love,” he said. “And I have a lot of love. Oh, my God, I do.”

Chef Michael’s eyesight was too poor for him to read from a notecard, so Broder, kneeling at Michael’s feet, gave him cues to keep him on track.

“We’re having Cornish hen with Grand Marnier and lemon juice,” Chef Michael said. “It’s so delicious it makes you want to slap somebody.” Again, the room erupted.

As I looked around at the enthusiastic diners, listening to Cheryl revealing the secret to her hot links (it’s tapioca), it occurred to me that researchers would have a hard time quantifying the impact of an event like this. It might not, in the end, slow anyone’s cognitive decline; it would probably be unfair to expect that any single intervention could. But, if it provided a few minutes of joy and novelty for these elders, if it reinforced their humanity and dignity, if it thickened their connection to a community—if, as my brother David had said, it snapped them back to themselves, just for a moment—that seemed like enough. I found myself wishing that my dad could have experienced a Dinner Party, that I could have been there with him.

I was jolted out of my reverie by a piece of lemon pie, which was buttery and tart with a golden graham-cracker crust. Miss Peche was addressing the group without her notecard. “I’m here to tell you about one of the things my mom made for me,” she said. “It was lemon pie.” Veering off script, she thanked the center’s staff and her aide of ten years, who was next to her, filming.

Later, I asked Miss Peche for her verdict. “It isn’t the same crust as my mom’s, and her pie was more pudding-y,” she said, and took another thoughtful bite. “But yes, it does bring back memories.”

She glanced at my notebook. “This dinner—everything was beautiful,” she said, and gave me a sharp look. “You write that down!”

Chef Michael was seated near Joel Kramer, the director of the neuropsychology program at the Memory and Aging Center at U.C.S.F. When Kramer started to reminisce about his teen-age job, at a Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Michigan, I unexpectedly fell into a memory hole of my own. We didn’t eat shellfish in my Jewish home, but, when I was six, on a summer road trip from Minneapolis to the East Coast, my parents let me try HoJo fried clam strips. I’m sixty-one now, but I could still remember my family sitting in the booth, and how the vinyl seats stuck to the skin of my legs. As I popped a greasy, salty, sweet nugget into my mouth—knowing it was treyf—I felt a faint fear that I would be smote dead.

That brain circuit hadn’t fired in decades, and it might never have again were it not for the Dinner Party. A cascade of images from that trip followed: my first glimpse of an ocean; the iron forge at Sturbridge Village; throwing up on my brother in the back seat of the Vista Cruiser. It’s not that I’d forgotten those incidents, not exactly, but suddenly they snapped into focus—a piece of the past, and of myself, restored.

A couple of weeks later, I returned to the center as a more typical lunch was coming to an end: lasagna and green beans that wouldn’t have been out of place in a middle-school cafeteria. An old Jackie Chan film blared on the TV. I asked after Chef Michael, but he had been out sick for a week—I would later hear that he’d had a rough go but recovered and was back to his routine. When I saw Miss Peche, sitting with three other women, I asked her again about the pie. It had been delicious, she said, though it would have been even better with a flaky Gold Medal crust.

I recognized one of the group as Laura, the woman from the video who didn’t make it to the Dinner Party. “I’m sorry you missed that good gumbo,” I told her.

She looked at me with a cheerful but uncomprehending expression. “I don’t even know what gumbo is,” she said. “I’ve never tasted it.”

I was about to describe the hearty stew that I had tasted at the Dinner Party, and to mention her friend Niecey, which might have jogged her memory, when I caught myself. Maybe it didn’t matter whether Laura remembered what gumbo was; after all, I had already heard her talk about what the dish meant to her.

In the video, Laura explained that, when Niecey died, she was too sad to return to the Adult Day Health Center. Going there reminded her of what, and whom, she had lost. But then, Niecey appeared in one of Laura’s dreams. “She cussed me out and told me to get my fat, white ass back there,” Laura recalled. “ ‘You turn to people who are suffering and you give them kindness and strength.’ ” In that moment, Laura looked straight at the camera, as though urging her audience to hold onto what she was about to say. “I want people to know,” she said. “Niecey was a great woman.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com