The golden age of remote work seems to be ending. The Wall Street Journal is reporting that even tech firms (the first industry that told employees they could work from home forever just a few years ago) are getting engineers and project managers back in the office. The economic blogger Kevin Drum, formerly of Mother Jones, has taken note of the increasing anti-remote literature and is making a bold prediction about the future of work: there is none. It’s not going to look much different than it’s ever looked. That’s because the remote work revolution just isn’t going to materialize.

“Companies that put up with [remote work] for a long time are finally getting sick and tired of [it],” Drum wrote on Sunday. The reason for that is fairly straightforward: Working from outside the office “simply isn’t as productive as office work, no matter what remote workers say. Too much evidence has piled up to credibly deny this any longer.”

He pointed to return-to-office pushes at tech companies where most jobs could be remote, particularly Salesforce, Google and Meta. Then he highlighted four key pieces of evidence, although asterisks abounded. Still, Drum is worth listening to on this matter: Along with figures like Brad DeLong and Ta-Nehisi Coates, he thrived in the Wild West days of blogging, and at Mother Jones and independently he displayed an aptitude for paying attention to what the data says about major economic subjects and cutting out the noise.

For his part, Drum expects most of the private sector to go back to work in the physical sense. “There was remote work before the pandemic and there will be a little more after the pandemic,” he wrote. “But it’s going to be measured in a small handful of percentage points, not as a revolution in work.” Drum, who since leaving Mother Jones in 2021 has been blogging semi-daily from his home in Orange County, Calif., did not respond to Fortune’s request for comment.

Most remote workers insist they won’t be going back to their sad desk lunches, and many companies are still promising they won’t take attendance ever again, but maybe they should listen to Drum’s warning. Here’s why the tide is turning against remote work (rightly or wrongly).

#1: Remote work is bad for new hires and junior employees

This one is not nearly as controversial as it sounds. Especially when you’re new on the job, being physically present can be an enormous leg up; even the supposedly anti-office Gen Z workers acknowledge the overwhelming truth of this.

“We know empirically that [new Salesforce employees] do better if they’re in the office, meeting people, being onboarded, being trained,” CEO Marc Benioff said in March. “If they are at home and not going through that process, we don’t think they’re as successful.”

That could also hurt companies; a recent Paychex survey found that 80% of new hires will quit a job if they had a poor onboarding experience—which is much more likely to be the case if they’re welcomed aboard from a distance.

Nearly one-third of employees told Paychex they found their onboarding experience confusing. That figure jumped to 36% for remote workers, who were most likely to feel undertrained, disoriented, and devalued after onboarding, compared to their in-person counterparts.

As a one-time entry-level product manager, Drum wrote, “I can’t even imagine what it would have been like trying to learn what I needed to know if everyone I had to work with was available only via Zoom or phone or Slack. It’s one thing for existing teams to continue working well from home; it’s quite another to get a new member of a team up and running.”

It’s a shame, because proximity bias poses an enduring threat to career advancement. But attempting to get around by staying home as an entry-level worker means you’ll be swimming against the current.

#2: Workers admit that remote work (sometimes) causes more problems than in-person work

When executed incorrectly, hybrid work plans can create discordant, unproductive teamwork. That’s especially true when teams don’t make an effort to align their in-office days.

Also, remote work has its fair share of downsides. Drum linked back to McKinsey research he had highlighted in his “midterm report on remote work” from December, which found that remote workers are much more likely to report mental and physical health issues and hostile work environments. That’s not the worst of it: 60% of bosses recently admitted that if they had to make job cuts, they’d come for their remote workers first.

Usually, Stanford economics professor and remote work expert Nick Bloom has told Fortune, companies mess up these kinds of plans because they fundamentally misunderstand why people want to work in-person or remotely in the first place. The disaster scenario, which too many companies end up in, is when everyone must come in two days per week or so, with no further clarity.

“Then they come in and realize their team is all at home, which defeats the purpose,” Bloom said. “They didn’t come in to use the Ping–Pong table, and there’s no point in coming in just to shout at Zoom all day.” Plus, Bloom, who advocates for organized hybrid arrangements, agrees with pro-office zealot Benioff that newer workers need the office most.

#3: Remote workers put in 3.5 hours less per week compared to in-person workers

Sure, it’s true that remote workers squeeze in errands, exercise and laundry between 9 and 5, but just how much? A working paper submitted to the National Bureau of Economic Research in January found that remote workers worldwide save 72 minutes a day on average just from avoiding their commute, and that on average, of that time saved, 40% goes to extra work.

Drum is unconvinced about the effects in America—and so is the federal government’s own dataset.

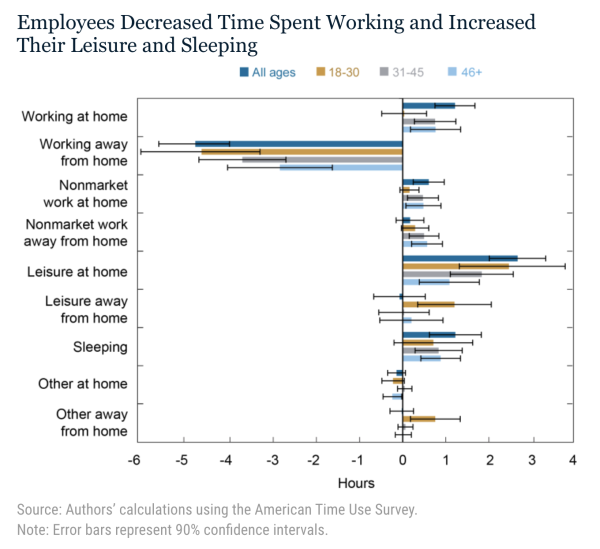

For his part, Drum sees a 3.5-hour decline in hours worked, and he got the figure from an October 2022 report by Liberty Street Economics, an arm of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Researchers David Dam, Davide Melcangi, Laura Pilossoph, and Aidan Toner-Rodgers made calculations based off the American Time Use Survey, a nationally representative survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics that measures both the amount of time people spend on various activities and where the activities occur. In a damning chart, they found that remote workers “decreased time spent working” and instead increased their time spent on “leisure and sleeping.” The chart clearly showed an increase roughly between three and hours in time spent on things that are, well, not work.

Maybe in the rest of the world, workers are taking time not spent commuting and plowing it back into work, but the government’s own data in the U.S. tells a different story. A 3.5 hours less story.

#4: Productivity plummets on days when everyone is working remotely (anecdotally)

In March, Drum wrote a post highlighting what the CEO of an HR tech firm told the Wall Street Journal: On days his team is working remotely, new subscriber counts plummet 30%. But that’s just one anecdote; even Drum himself says the stat is amazing—“if [the CEO] isn’t exaggerating.”

A piece of hard data in Drum’s favor here is the shocking decline in productivity across five straight quarters, unprecedented in the postwar era. EY-Parthenon’s chief economist Gregory Daco told Fortune that he’s heard similar stories from clients across sectors of “reduced productivity because of the new work environment.” Daco added that remote work is only one piece of the puzzle here. “The difficulty is that there is no magic productivity wand.”

Other experts are more skeptical. “What I suspect is if you took out all the time at work talking about the Super Bowl, politics, your weekend, etc., working from home would involve more actual working minutes [than working in an office],” Bloom, the remote work evangelist, told Fortune’s Tristan Bove.

Workers themselves certainly beg to differ on this point. According to a recent Pew Research survey, pro-remote workers (especially parents and caregivers) have a better work-life balance and are more productive and focused. According to an October 2022 survey of white-collar workers from Slack’s think tank, Future Forum, those with full schedule flexibility showed 29% higher productivity scores than employees with no flexibility at all, and remote and hybrid workers reported 4% higher productivity than their fully in-office counterparts.

The Pew survey respondents acknowledged that not being in the office could be hurting their opportunities for advancement, mentoring and making connections, but they believe they’re more productive.

But the tide is turning for many reasons, and whether workers believe they’re more productive remotely or actually are, they may not have much of a choice in the matter.