Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

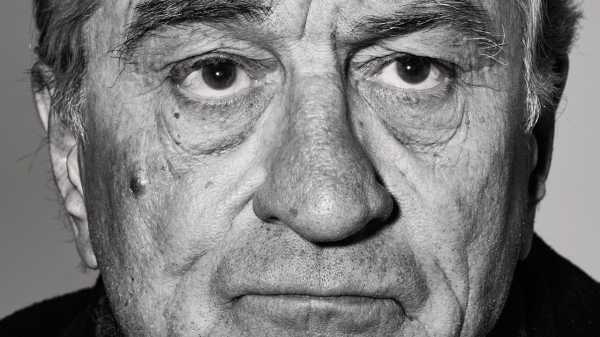

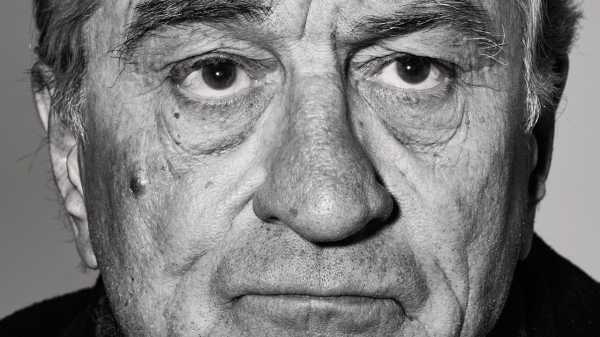

Robert De Niro is, famously, a man of few words. In the past two years, those words have included “punk,” “dog,” “pig,” “con,” “bullshit artist,” “mutt,” “idiot,” “national disaster,” “embarrassment,” “disgrace,” “fool,” “bozo,” and “Jerkoff-in-Chief”—all directed at Donald Trump. At seventy-five, De Niro has turned political pundit, often in terms that you’d expect to find in a Martin Scorsese movie. In return, Trump has called him “a very Low IQ individual.”

Scrapping with Trump isn’t the only thing keeping him busy: in the last decade, De Niro has appeared in more than two dozen feature-length movies, from HBO’s “The Wizard of Lies” (in which he played Bernie Madoff) to the comedy “Dirty Grandpa” (in which he played a dirty grandpa). He just shot his ninth film with Scorsese, “The Irishman,” playing the Mob hit man who killed Jimmy Hoffa (who is played by Al Pacino). The Tribeca Film Festival, which he co-founded, in the wake of 9/11, is headed into its eighteenth year. And he has a recurring role as Robert Mueller on “Saturday Night Live.”

I met De Niro recently in his corner office at the Tribeca Film Center, situated in the sliver of downtown Manhattan sometimes known as Bob Row, encompassing two restaurants, Nobu and Tribeca Grill, that he co-owns. The room was covered in memorabilia, including a call sheet from “A Bronx Tale,” a framed dagger he picked up in Kuwait, and an oil portrait of his father, the late painter Robert De Niro, Sr., the subject of a 2014 documentary. These were the same offices where, on October 25th, security intercepted a suspicious package addressed to De Niro, containing one of a slew of pipe bombs sent to high-profile Democrats and critics of the President. As De Niro sipped on tomato soup, we began by talking about the incident. A week later, we spoke again, on the phone. Our conversations have been edited for clarity and condensed.

When did you find out about the bomb? Where were you?

I was in my house, working out. I got a call early in the morning that it was there in the office.

What went through your head?

There’s so many crazy people. The state of the country is so terrible now, with a person who has set such a bad example of bad behavior. I’m waiting for the bad dream to end. So what are you gonna do? What am I gonna do?

How much blame do you place on the President for something like that happening?

I think on a subconscious or subliminal level, and many other levels, it gives the O.K. to other people who are maybe more on the verge of thinking, or fantasizing, that he’s somehow given the O.K. to do that. I used to think, Well, maybe once he becomes President, he’ll maybe—he’s a New Yorker. Not that that means anything, in certain ways, but it does in others. I thought, Maybe he’ll come around. But then he’s been worse than I ever could think. ’Cause he has no plan. He has no center whatsoever. He even gives gangsters a bad name. ’Cause a gangster will give you his word and will pride himself—or herself. He doesn’t even understand that kind of logic. He thinks he’s slick and all that. There’s something wrong with him mentally.

It’s interesting that you compare him to a slick mobster guy—

Well, he thinks he’s a mobster. He’s a mutt. And I’ve said that before. I’ve said it publicly. And everything that he says about other people—that they’re losers, that they’re this and that, every terrible thing he says—he’s really saying about himself. I don’t know what his parents did, I don’t know how they treated him, whatever, but it’s all projection.

I imagine that a lot of people out there in the country who admire him are also people who’ve admired you over the years, even just demographically. Older white men tend to like President Trump. And I would think that they might see in him things they could have seen in Vito Corleone or Jake LaMotta, these guy-guys who don’t take any bullshit.

There’s a difference. He doesn’t represent—he likes to act like he does, I guess from that stupid show he did, that a lot of people bought and believed that he would act a certain way. And I remember seeing a documentary about these two writers who helped create the whole aura, the whole look, the office, the presentation, and everything. These two schlubby guys, two writers. They said, as I remember it, they said, “We created this thing.”

You mean the makers of “The Apprentice,” who created the character.

The character. And now he’s in reality and he’s got to make real decisions. I don’t know if I’m answering your question. You’re saying people who like me—yes, there is a similarity with my characters. But I’m an actor. Those are characters I play.

Have you seen any kind of backlash from your fans, people who are Trump supporters?

No. I can’t worry about that.

Did you ever interact with him personally over the years?

I met him once at a baseball game.

What happened?

I was there with a few of my kids. He came into the box that I was in, said hello, and we shook hands. I never wanted to meet him. Because I think everybody’s onto what he’s about. What amazes me is that people buy into it—people who have a responsibility to the country, not to him. They have gone along with this. And we all know who they are. Republicans who can go into the private sector and get a job making more money in a law firm or something. Instead, they opt to stay in this situation with a criminal and sell themselves. And everyone who’s involved with him has been tainted, and people will never forget it. The only one is Mattis, a little bit, and he stumbled the other day when he went down to the Mexican border and tried to give a Pancho Villa story. I felt bad, because I have great respect for him, and we all do.

And now he’s gone.

Yeah, I don’t blame him. It’s dangerous that he left. We’re in a crisis in this country. We have a fool running it, and, when a guy like Mattis finally has to go, we have a lot to be concerned about. I don’t see how we can go two more years with this guy.

I assume that the reason the person sent you a bomb was because of what you said at the Tony Awards, which was not what I expected to happen at the Tony Awards. Was that a decision you made beforehand or was it impromptu, to say, “Fuck Trump”?

It was impromptu. I feel that more people should speak out against him and not be genteel about it. At Tribeca, I said, “I’m tired of being nice about it.” They have ads on CNN about truth. “This is a banana, this is an apple,” or whatever they have. That’s what we’ve come to with all the “fake news” stuff.

How did your role as Robert Mueller on “Saturday Night Live” come about?

Actually, my wife, who—we’re [searches for the word and pulls his hands apart] separating now—but she had thought of it. I said, “What can I play on ‘S.N.L.’?” Because I love “S.N.L.” And she came up with Mueller. So I told Lorne Michaels. This is how I remember it—I could be wrong.

Is there a key to playing Mueller?

Mueller is the hope. Mueller is our hope. And he’s doing everything—he’s doing it perfectly.

But he’s not someone who’s seen in public very much these days. How did you decide to play him?

I didn’t. It’s a skit—the makeup and everything. They put jowls and prosthetics on, the chin, the nose, eyebrow.

Did you grow up in a political household?

Not really. Some but not much.

What was your experience of the antiwar movement, the politics of the late sixties, early seventies?

I felt that the war was not a just war. And, you know, it was a turbulent time in America, as I think it is now. It might even be worse now.

Did your parents have a particular kind of politics that they spoke to you about?

My mother was a little more leaning toward the left, in some ways, but never telling me much. My father was an artist. He was apolitical, pretty much.

I loved the documentary you participated in a couple years ago about your father. I didn’t realize that your parents were both very well-regarded artists who were exhibited by Peggy Guggenheim and were of the same milieu as people like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. They’re mentioned in the same circle as Anaïs Nin, Henry Miller, Tennessee Williams. Did you know those people growing up in Greenwich Village?

No, I was just a young kid. I was there but not really there, not exposed to it. Then my mother and my father, they split up. My father went off.

I read that they both wrote erotica for Anaïs Nin?

They might have. I heard that, yeah.

You haven’t read it?

No.

The image I had of your childhood was all about roaming around Little Italy and being in a street gang on Kenmare Street. Was that a contradiction, that you had parents who were part of this downtown intelligentsia?

That was one part. They were both parts of my life when I was a kid.

Were you rebelling?

Probably, in some way. Who knows. It was a good part of my life. I wasn’t, like, rebelling. That’s where I felt comfortable.

It seems like the purpose of the documentary was to help reintroduce people to your father’s work and revive his reputation as an artist.

I wanted to make a documentary about him so that my kids could see what their grandfather did and be aware of all the art that he’s done. He was prolific. I have it around in many places in my house, of course.

I was also very interested in the fact that he was a gay man living in the pre-Stonewall era. Do you know if he ever found romantic fulfillment?

No, I don’t know. He didn’t expose me to that. There was somebody I met one time in Europe, but other than that—and I wasn’t sure even with that person.

What was your understanding as a child of him being gay? Do you remember figuring that out?

I didn’t figure it out. I didn’t know. I think my mother told me later. And then I guess I said, “Well, O.K.”

At what point in your life was this?

I guess in my late twenties, early thirties. He didn’t sit me down and say, “I’m gay,” a heart-to-heart father-son conversation about it. He just wasn’t that kind of person.

That was around when you were making movies like “Mean Streets,” which has that scene of a flamboyant gay man screaming come-ons to people on the street from a car window. How did your father’s sexuality resonate with you as a young man who was coming into his own as an actor and as an adult?

I just didn’t think much about it, really, other than that’s what it was. He was always very much to himself. So I didn’t ask any questions.

In the documentary, he comes across as someone who got really lost in his work. Do you feel you’re like that? Do you see parallels?

Yeah, there are certain things. My impression was, he’d be very cynical about people and certain affectations they’d put on. I thought it was funny. As you get older, you realize you do more things like your parents than you realize, things I do now that my mother used to do.

Like what?

I like to read the paper a lot. She always would do that. Lately, with all the—not to get back on Trump, but I’ll say this—before he got elected, I thought, He’s going to claim that he “shook it up.” Oh, he did shake it up. He made us much more aware, and there should be more courses in school with kids knowing the basics of what our country is about.

Like civics courses?

Exactly.

Did you have to take civics?

A little here and there. There were requirements at school.

People have always been fascinated about the lengths you’ve gone to for roles, whether it’s gaining weight or learning boxing or Sicilian. Do you feel like you’ve changed as an actor? Is that something that you still do?

I have changed as an actor in the way I approach a part. For me, it’s for the better. I still enjoy it. When I was younger, I gave a lot of attention to things I feel maybe I have to give less attention to now. Like being a musician. The more practice you get, the easier it is, the more you can do things with less effort. Certain things, not other things. Other things are just as hard.

Like what?

Certain parts that are less close to me. They’re wonderful parts, but I have to work harder in other areas with those.

What’s been the hardest role for you to do recently?

Oh, God. Well, in some ways, the one with Marty Scorsese, “The Irishman,” based on “I Heard You Paint Houses.”

You’re done shooting it, right?

We shot it, yeah.

You play the character over many decades. Was that a challenge to play a younger person? Did that involve some physical transformation?

Some, yeah. We had someone who was always on the set keeping an eye on posture and stuff. Going up and down the stairs and things. You forget as you get older that certain things are not the way you did them twenty, thirty years ago. So those kinds of things I was always trying to be aware of. Because they would make you younger technologically with, whatever, C.G.I. and all that stuff. But you still had to have the physical movements that were closer to the age.

They’re using V.D.X. to age you and Pacino backward. Have you seen the results of that?

I saw a little of the test. They look pretty good, from what I saw. I joke that it’ll extend my career.

It seems like you’ve gotten so much out of physical transformation in the past. Is there something that’s lost by not having to put latex on?

No, we still have that—the older stuff, especially, there’s makeup. I don’t know how to act younger, other than physically. Older is easier. You can put makeup on.

This movie cost a hundred and forty million dollars to make.

Is that what it cost?

That’s what I’ve read. And it was picked up by Netflix because Paramount didn’t want to finance it. As someone who helps run a festival for independent filmmakers, what does that tell you about where the industry is headed?

Well, we were grateful that Netflix could do the movie, because the way we wanted to do it, the way Marty wanted to do it, we needed the money to do it this way. I mean, I know there’s other controversy about how you release it and this and that. That’ll be worked out.

You mean whether it’ll play in movie theatres?

Yeah, stuff like that. It’ll be worked out, I think, in the right way.

Do you see the industry changing, with streaming companies funding independent filmmakers—and even people like Martin Scorsese? It seems like a huge shift.

I don’t know. You know, even actors could be—not that actors will ever be replaced or replaceable—but they could somehow in the future, things could be done where—nothing would surprise me.

It’ll all be robots?

Or they’ll do a likeness that you have to fight for the right to own, or something. It could go anywhere.

If they had this V.D.X. technology forty years ago, they would have just aged back Marlon Brando for “The Godfather, Part II” and not needed you.

There you go! I was lucky.

It seems to me that there’s a lot of angst in Hollywood about films not being seen on the big screen. What do you think about the idea that, even if “The Irishman” is given a theatrical release, probably a lot of people would see it on a small screen? Is that a trade-off for having it funded?

I think a movie, especially this movie, and with us involved and Marty, it’s gotta have that venue, that big-screen thing. It’s the only way. Will people be watching it on their iPhones? Who knows. Is that the ideal way to look at it, or on the computer? No. But people look at things in so many different ways. Everybody understands that the big screen is the format it should be in, at least at the outset.

But it seems like there’s going to be more of a gray area between what’s a movie and what’s television. The Coen Brothers have this movie on Netflix, “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs,” and Alfonso Cuarón, with “Roma.”

Did Cuarón’s movie open in the big theatre first?

It did.

It was terrific.

But most audiences will see it on their televisions or their laptops.

I think our movie should be seen on a big screen. Alfonso Cuarón’s movie should also be. It’s important to see it that way. Though, these days, they’re big screens, televisions—like this one. [Gestures to his very large flat-screen.] They’re bigger than when I was a kid.

Yeah, that’s pretty big.

It’s not a movie theatre, but, you know, it’s whatever.

The first decades of your career you mostly played dramatic roles. That seemed to change around the time that “Analyze This” and “Meet the Parents” came out. Was comedy something you were itching to do?

I mean, I’d done things that were—they’re not comedies, but “Greetings,” “Hi Mom!,” stuff like that. Quasi-comedy of a certain type, whatever the label would be. But, with “Analyze This,” Billy Crystal had this script and he wanted to get it to me, and so he got it to me. And I said, “O.K., let’s have a reading of it and let’s see.” Because I thought it would be kind of fun to do this if we got it right, and if we got the characters more real. Not doing caricatures but doing characters.

In a way, that character is a comic version of mob characters that you had been playing in dramas. Did you have a feeling that you wanted to play off your own image?

Yeah, I didn’t mind that. I thought it would be O.K.

I read that you turned down the Tom Hanks role in “Big.”

Yeah. What happened was, Penny [Marshall] wanted me to do it. I wanted to do it, then I didn’t want to do it. Then I said, “I want this much,” and they said no. So that was that. And, I don’t know, it just got into a pissing contest about the money. So they went the way they did with Tom Hanks, and that was fine.

That would have been a very different movie.

Yes. And I wasn’t sure—there was something about it I wasn’t quite . . . the innocence the character would have. How do you act like a kid when you’re older? I just wasn’t sure of the whole makeup of the thing. I wasn’t sold on it, the way the process would go with Penny and stuff. Maybe I was relieved, in a way.

Of course, you worked with Penny Marshall two years later, in “Awakenings.”

She did a very good job on the movie. I liked Penny. She had a good sense of humor. I’m sorry to hear that she passed away. I wish she had taken better care of herself. She would have been around a lot longer. I think she had more in her—she could have done more. She was young, as far as I’m concerned. She was my age! I’m always sad when someone goes—Robin, too. Poor Robin. Anyway.

Are there other parts you’ve turned down over the years that you kick yourself for not taking?

No. I’ve been pretty lucky. ’Cause I’ve taken most—not most, but, a lot of the parts, I say I’ll just jump in and do it. There was one that I didn’t do. Jonathan Demme was asking me to do . . . uh . . . the one that Anthony Hopkins did.

“The Silence of the Lambs”?

“The Silence of the Lambs.” Jonathan was calling me about it, and I had to make a decision about something I was doing, and I didn’t want to hold him up, and so then he decided to use Anthony Hopkins. Which was fine, you know. It was just one of those things. But I didn’t regret it, and I’m happy for all its success and how wonderful Anthony Hopkins is in it.

I want to ask you a little bit about the #MeToo movement and Time’s Up and what’s been happening in the past year in Hollywood. Were you surprised by the level of sexual abuse and harassment in the movie industry?

Yeah, I was. I was. I wasn’t aware—everything with Harvey and so on. I mean, now that I see how many people were—it was not good.

Did you ever have actress friends confide in you over the years about something that happened to them or some quid-pro-quo scenario that you, in hindsight, think, “Well, that might have been more widespread than I thought it was”?

Well, here and there, sometimes. Someone would say so-and-so—but had no idea it was the way it was. I’m not going to hear certain things, because nobody’s going to—sometimes a friend might intimate about something, a certain person. Nothing too graphic, nothing that would warrant my saying, “Well, they shouldn’t have done that, let me say something about it.” Because people didn’t want to bring it up or they were embarrassed or they didn’t want to start something. But I see now where it was.

What do you think the responsibility of men is in the industry, especially men with a lot of influence and clout such as yourself, to change things?

I mean, if anybody makes me aware of something, then I will try and do the right thing about it. What I think of, automatically, is that somebody would do something where they use me as the get-to person in order to get what they want, or something like that. And I normally wouldn’t hear any of that. I just wouldn’t hear it, because they know it’s wrong. But, if I did hear it, I would do something about it, say something: “That cannot be done. You cannot do that, period.”

Illeana Douglas, your co-star in “Cape Fear” and “GoodFellas,” told The New Yorker her story about Les Moonves, who cancelled her CBS contract after she resisted his advances. Are there actresses you feel should have gone farther, should have had longer careers, but were caught up in this system?

I don’t know, because sometimes you can blame that, but it might just be somebody—because I always feel if you’re wanted for a part, those kinds of things will go away. You’re going to get the part. I don’t know what Illeana’s situation was, and she could very well be right about what happened to her. I don’t know the specifics. I read something about it. And maybe that was the case with her. So that’s not good.

Are you saying you don’t know if you believe her?

No, no, no, of course I believe her. No question about whether she was telling it the way it happened. I totally believe her and understand. It’s a situation that, again, as a man and as a person in my situation, I do not see and I’m not aware of. People can infer things, but a lot of times people don’t like to talk about that too much to me, so I don’t hear it. But it’s terrible for any woman, anybody who goes through that kind of harassment. I was reading about this girl Eliza Dushku. She played my daughter in “This Boy’s Life.” She was, like, twelve then. So then I’m seeing she said that she was harassed. On a movie, you have to set a tone if you’re a person that’s respected by everybody. You have to set a tone. If you do certain things, it sort of trickles down. It’s like our situation with Trump. It’s like in a schoolyard, being picked on by a bully. Then the other people follow the bully, and they might take the liberty to do something that they wouldn’t do if the bully set a good example. Even if it’s a joke and it might seem funny to the person doing it, bottom line is, they have control over your future and your life. ’Cause if they want to say, “I don’t want them working for me”—and they might not say, “I don’t want them working for me.” Someone might say, “What do you think about her?” “Eh, I don’t know, maybe find somebody else.” All of a sudden she’s out of a job. What’s she going to think if she was harassed? Because she didn’t put up with it, now they’re going to let her go, but in a way that she can never prove. That’s insidious. It’s terrible. It’s wrong.

Obviously, it’s harder for women to have longevity in Hollywood. Meryl Streep does, but we’ve seen so many actresses all but evaporate after fifty, because there aren’t as many roles for them. Cathy Moriarty, for instance, is fantastic in “Raging Bull.”

Yeah, she was. Cathy was great in “Raging Bull,” and she’s done other things. We even did a little thing in “Analyze That.” Listen, sometimes parts don’t come along that can utilize the best of what someone has for an actor, whether it be man or woman. That’s why Meryl’s so great—she’s so versatile, she does so many different things. That always helps. And she has that longevity because of it.

But you don’t think it’s different for men versus women?

Yeah, it is, of course it’s different. The age thing is a big part of it, yeah.

You’ve played a lot of men who are aggressive and macho and violent, everyone from Max Cady in “Cape Fear” to even Jake LaMotta in “Raging Bull,” who beats his wife when he thinks she’s cheating on him—characters who have what we would now call “toxic masculinity.” Do you see them in those terms?

With “Raging Bull,” what I liked about the book—I read it, and I was doing “1900” with Bertolucci in Italy, and I told Marty, “Read this book, because it’s not a great book but it’s got a lot of heart.” And I like the idea of the weight, too—he gains this weight. I thought, that’s so graphic, the guy just blows up, he’s out of shape. So Marty read it, and we talked about how we were going to do it, and I ate as much as I could. The first fifteen pounds was fun, but any fantasy about eating as much as you want quickly dies by the first twenty pounds. And I went to sixty. I remember Marty and I talking about jealousy. People say they’re not jealous. And I said, “I think people get jealous.” Because at that time there was free love and this and that. I said, “I don’t know, I think people get jealous.” I know I do. Especially in the sixties, in the free-love movement—well, no, you still get jealous, you still feel upset if somebody you really care about is with somebody else.

And then he turns violent.

Yes, and he was violent—and I’m forgetting because it’s so long ago. [LaMotta] wrote a book, he and Pete Savage, who passed away many years ago. They had seen “Becket,” the play that Anthony Quinn was in with Laurence Olivier, and they told me they liked the idea of the two guys and modelled some of it after that: the bond between these two men. And there were certain things in it that Jake was violent. I don’t know if he actually hit Vikki or anything—

He did in the movie.

He did in the movie, but we put that in. And sometimes you go so far, but Jake was always with us and his brother, Joey. And I met the actual Vikki in Florida with the writer, the original screenwriter, Mardik Martin, before Paul Schrader came into it. But she loved him very much, said they were good friends, as I remember. They had their disputes. But we put our own thing into it, as you do. You can’t expect everything to come from them, to be totally honest about certain stuff. And they were very helpful, Jake was. They were just happy the movie was being made. Anyway, that was our spin on it.

At some point you talked with Scorsese and Schrader about doing a sequel to “Taxi Driver.” Why did that interest you?

People would ask me from time to time, “Where do you think Travis Bickle is now?” And I’d say, “That’s a good question.” And I remember asking Marty, “What do you think?” So he said, “Yeah, let’s ask Paul, let’s talk about it.” So we did, and Paul came up with something, but it never was quite—we never could get to something that we felt would be right.

Where did you imagine he was now?

I don’t know. I didn’t do much thinking about it.

Living in a van in Florida sending out pipe bombs?

Yeah, right! Exactly. He coulda been that. I mean, Paul really would know the trajectory better than us, of course. And he had an idea, but we just felt it wasn’t there. Maybe there will be when I’m eighty-five years old. [Knocks on wood.] If I’m still around, we’ll come up with something.

I think Schrader said the character would have been dead six months after the movie ended. He was on a spiral. But I did see you were interested in his “rage and alienation”?

Because I’m from New York, and the alienation—I could identify with that, and I’m from Greenwich Village. And you still feel it. I think that’s why a lot of people identify with it, no matter where you’re from, what your background, you come to the city and you’re alone here. It can be a cruel place, New York. It can be a lonely place.

I do find it interesting that you’ve played so many men who’ve felt this rage and alienation—even Jack Byrnes in “Meet the Parents,” who can’t access his emotions. Between Trump and #MeToo, it’s been a rough couple years for masculinity. What does being a real man mean to you?

Being a real man is not just being a man the way you’d think. If you think that I should do this or that or I’m not a man—I’m sorry. Men are much more complex, and there are many more sides to them. You gotta be sensitive. You gotta care about people, have empathy. And someone like Trump, he’s got something screwed loose in his head. But it’s through some deep insecurity that he actually behaves the way he does, because it’s all bullshit. And people buy into that with him, with his behavior. It’s sad. That’s not what life is about. But some people are in cultures where they’re all like that, they all reinforce it in each other. The sensitive ones are afraid to say anything. I made a movie, “A Bronx Tale,” and those kids, they don’t want to look like they’re not tough with their peers. The bottom line is, you gotta be an individual and you gotta stand up and be who you are.

That’s a good way to put it: toughness. People see Trump as tough—

He’s not tough.

—but your work has explored toughness in a lot of different varieties, and there’s good toughness and bad toughness.

You don’t have to behave the way he does. That’s just bullshit bravado. It has nothing to do with anything. If you’re tough, you’d be making decisions that he hasn’t made.

You’re seventy-five, you have a big family, you’re very busy. Do you ever consider retiring like Daniel Day-Lewis, or do you think you’re going to keep taking on multiple roles a year?

I like to keep busy. I have another movie that hopefully I’m going to do with Marty. We’re supposed to do it. I don’t like to talk about it. I think that’s going to happen. [Knocks on wood.] And other things—David O. Russell. I love doing projects with them. And other things with my kids and my family and my life. I’m always doing something. And I like to keep busy. What else am I gonna do?

Sourse: newyorker.com