Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

A few years back, I returned from a trip to Rome with a coffee-table book of photographs of the city taken over the decades. In the months that followed, I leafed through the pages most nights, reading the captions over and over in an effort to improve my Italian. I didn’t become fluent in the language or in the pictorial history of Rome, but the book made clear that the city has been photographed every which way: streetscapes, shadowy abstractions, paparazzi shots, pictures of monuments, official-looking tableaux of soldiers massed at attention, documentary images of poor migranti in shacks on the periferie, or outskirts—and priests and nuns in situations alternately solemn, comic, and absurd. With all that visual history in the registry, the challenge for any photographer in Rome is how to make things new.

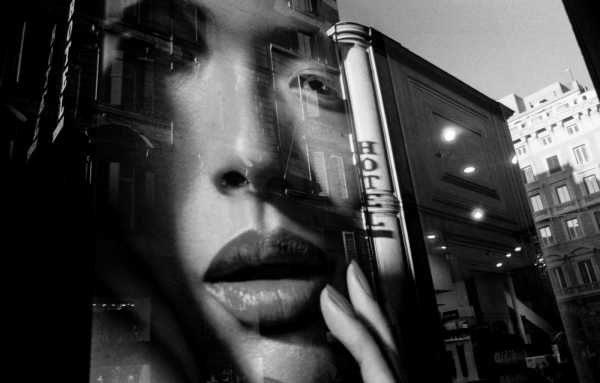

The appeal of Perry Hall’s street photography from Rome is that it answers the question without ever openly asking it. Hall uses a Leica and black-and-white film, but his work is light of touch and free of hat tips to the past. Here’s a man in St. Peter’s Square clutching a rosary, his tired eyes tilted heavenward—but the rosary is only one accessory for his pilgrimage, along with an N95 mask and an aerodynamic cane. Here’s a woman on a hilltop overlooking the city, her arms spread wide, as if to say, “Behold!” Her gesture is so spontaneous, her smile so broad, that her nun’s habit is almost incidental.

The details of Hall’s personal background suggest how and why his pictures defamiliarize Rome. A thirty-eight-year-old native of Chestertown, Maryland, he grew up “in and out of juvenile-detention centers,” as he explains on his Web site, and endured periods of homelessness starting at the age of eighteen. After hitchhiking back and forth across the U.S., he moved to Rome in 2014 and discovered street photography at the same time as he discovered the city. He is also a skateboarder—which may be one reason that his relationship to the street feels kinetic and engaged. His strongest images are not of Romans, as far as I can tell, but of people who, like him, arrived there from somewhere else.

Most of the streets in central Rome are made of sampietrini: rough-edged broken stones named for St. Peter, the first Pope. In Hall’s pictures, the sampietrini show up like place-stamps. An overhead shot of a burned-out car might suggest any European city, but for the presence of the stones and of a weirdly unscathed graffito on the body, reading “R O M A,” perhaps in reference to the Serie A soccer club, or to the Roma people, whose presence in Rome has stirred nativist anger, or to the city itself.

A comparison of two of Hall’s photographs suggests how hard it can be to see Rome afresh. One was taken in Piazza Navona, which is typically thronged at all hours by tourists taking pictures. The camera is focussed on Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers, with the stone hands of four gods thrusting baroquely into space. In the foreground, a young woman stands with a palm outthrust, as if saying, “Stop, don’t take a picture,” such that her hand mingles with those of Bernini’s gods in the frame. The image’s low contrast and lack of sharpness suggest that it was snapped from the hurly-burly of the piazza. The second photograph, taken at an intersection, shows two “Senso Unico” (“One Way”) signs pointing in different directions while a protruding forefinger points in a third. Maybe this hand gesture was spontaneous, but it looks premeditated, perhaps because the signs serve as a kind of embedded caption, so that the verbal sense overwhelms the visual.

The Rome I know is characterized by color: the tawny, fleshy ocher walls of so many buildings offset the ones made of gray stone, absorbing the sunlight, so that they look timeworn and radiant at once. Why, then, would a photographer working in present-day Rome choose to shoot in black-and-white? As I was pondering this, a family friend in his teens showed me some smartphone photos he had taken in rural Thailand. Their high contrast, exquisite textures, and brilliant, auto-modulated colors gave the scene a look that most amateur photographers couldn’t achieve until a couple of years ago. Seeing them gave me an insight about Hall’s approach—and about Rome.

Wherever you go in Rome, countless others have gone before you. Everything has been seen, done, or sought by somebody else. The streets are made of stones that are broken before they are put in place. There’s not a church, palazzo, piazza, or staircase in the centro storico that hasn’t been rendered by a succession of ace photographers working with state-of-the-art gear—and by centuries of open-air painters before them. The only way to make things new with a camera in Rome, then, is to be fully present in the given moment, which is ipso facto unprecedented. You’re in a piazza with an old-school camera around your neck. A horse trots up right in front of you, so that its head—nose and neck, harness and reins—frames a young man and woman nuzzling on the steps of a fountain. The man has his legs around her, as if he’s pinning her in a romantic pose. There before your eyes is a moment in Rome: edgy, hard to read, unrepeatable. You focus and shoot, and then it’s gone. The city’s heavy history can be a source of freedom—the freedom to see the place in the here and now, since there’s no other way.

Sourse: newyorker.com