Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Before social networks became the de-facto place for logging mundane moments from our lives, Apple’s iPhone and iPod Touch incorporated a feature that let users send footage they’d filmed directly to YouTube. The uploads were all assigned the same generic file names—IMG_0000, IMG_0001, IMG_0002, etc. The straight-to-YouTube button existed for only a few years, beginning in 2009, but that stretch of time coincided with the popularization of both iPhones and user-generated multimedia online, prompting an explosion of self-documentation. Millions of these early phone videos are still easily accessible on YouTube if you know how to search for them, like digital fossils of life a decade ago. A man shakily films a conversation with a dog breeder (IMG_0907); a washing machine rattles dramatically (IMG_0006); a child plays with a toy fire truck at a restaurant table (IMG_0129); fish float serenely in an aquarium, with the reflection of a phone visible in the glass (IMG_0116). These clips may have been uploaded to YouTube for the benefit of a few family members, or, in some cases, perhaps sent there accidentally. Many of them have accumulated only a handful of views; some have never been watched at all.

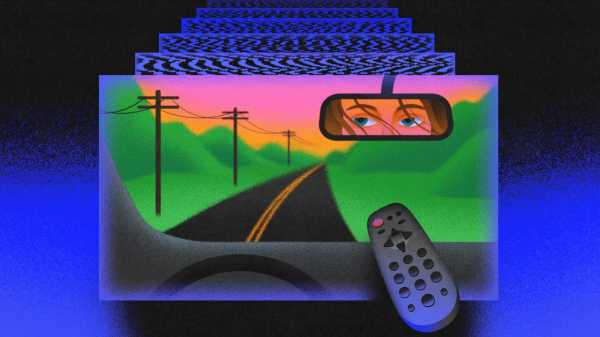

Riley Walz, a twenty-two-year-old artist and programmer in San Francisco, came across the videos earlier this year thanks to a blog post written by the engineer Ben Wallace, and he got hooked on watching them. “I was thinking maybe one in ten would be interesting, but all of them are,” Walz told me recently. In our current era of branded YouTube channels and professionalized TikTok personas, the amateurish, incidental quality of the videos seemed poetic. They weren’t there to pander to followers or to court virality; they were private notes left over from a less public-facing time. “They feel like memories,” Walz said. In November, as a kind of online found-video installation, he decided to create a Web site devoted to collecting the videos. Titled “IMG_0001,” it is formatted to look like a television screen, with an image of a remote that you click to turn the footage on. A box beneath the screen allows you to click forward to see the next clip. In the past month, more than six hundred thousand visitors have played more than six million videos.

A project that taps into nostalgia for the early Internet might seem surprising coming from a figure who squarely belongs to Gen Z. But Walz told me that growing up, in upstate New York, he “wasn’t one of those kids that would just watch TikTok all day or whatever.” Instead, he had a digital native’s version of an entrepreneurial streak. At the age of twelve, he began selling his services as a voice-over actor through the gig marketplace Fiverr, and fulfilled more than five hundred orders in the course of several years. He then used his earnings to lend money through the Borrow subreddit, a forum for informal peer-to-peer loans, and profited from the interest. His parents were “slightly concerned” but sanctioned his activities in the name of self-directed education. During high school, Walz hung out on Twitter and connected with a community of programmers, sometimes calling themselves makers or solopreneurs, who together hack bespoke Web sites that provide a particular service for fun or for profit. He was on the cross-country team, and to stave off boredom during training runs he coded a site, called Routeshuffle, that used an open-source mapping tool to generate random jogging routes. It was his first hit—to this day, around a hundred people pay for subscriptions to the widget—and the first in a series of impish digital projects (he considers the word art “too pretentious”). In 2020, he created a Twitter account for a fake Republican congressional candidate named Andrew Walz and—with the help of an A.I.-generated portrait, a fake Web site, and a fake listing on the candidate directory Ballotpedia—managed to get the account verified with a blue check.

Walz may have the soul of a hacker, rather than an artist, but his work exists in a lineage of prankster art that used the Internet both as a medium and as a venue. Beginning in 2010, the German artist Aram Bartholl created a series of “Dead Drops,” USB sticks implanted in city walls from which a curious visitor could download files. In 2016, an art collective known as MSCHF began creating provocative spectacles that spread online, including an interactive robot dog mounted with a paintball gun, and enormous red boots, seemingly modelled after the cartoon Astro Boy, which were sold as luxury fashion. Walz even interned for MSCHF in New York, after planting a newspaper box containing his resume in front of their office—with the proper city permission, which, he said, was surprisingly simple to obtain.

Walz’s work relies on manipulating online databases, but, like the work of MSCHF, his most clever projects bleed into the real world. In 2023, while attending the business program at Baruch College, Walz and his roommates, who liked to cook, had a running joke that their hacker-house apartment was a steak house. One day, a friend listed the address as such on Google Maps and, over time, others added fake glowing reviews. Then they turned the joke into a one-night pop-up steak restaurant, complete with a legitimate temporary alcohol permit, and hosted diners who may not have realized they were getting dinner cooked by a crew of young amateurs. The Times knowingly covered the prank, under the headline “New York’s Hottest Steakhouse Was a Fake.” Earlier this year, after taking a leave from college to work on an artificial-intelligence startup with friends, Walz installed an Android phone on a pole in San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood, where it can take in the sounds of passing pedestrians and cars. The phone runs Shazam continuously, attempting to identify any songs that are detectable, and uploads the noisy clips to a Web site. Walz named it “Bop Spotter,” after ShotSpotter, the urban microphones that are (fitfully) used to monitor gunshots. “This is culture surveillance,” he wrote on the Web page.

Walz’s interventions provoke strong reactions because they call attention to the hidden reservoirs of real-time personal data that power our daily lives in the iPhone era, whether we’re requesting driving directions or Googling a news event or looking for a restaurant recommendation. Where you are, what you’re looking at, and what you like is being tracked more or less constantly—either you’re doing it to yourself voluntarily, by taking a video with your phone and posting it online, say, or a corporate entity is doing it for you. A few months ago, Walz noticed that New York City’s Citi Bike system provided an A.P.I., a software interface from which he could draw real-time data about which bikes in the municipal fleet of more than thirty thousand were being ridden and where they ended up. He envisioned a project identifying which individual bikes had travelled the fastest or farthest on a given day, so he set up a repeating download of the data. He figured the results would be of amusement only to New York locals. Then, on December 4th, the C.E.O. of UnitedHealthcare was fatally shot in midtown Manhattan, and rumors proliferated that the alleged shooter (later identified as Luigi Mangione) had used Citi Bike to flee the scene. Walz realized that he had downloaded the system’s data from the time of the crime, so he trawled through it and matched a trip that had ended near Central Park shortly after the shooting. After trying and failing to reach a reporter with the tip, Walz posted it on X.

His message was met with vitriol and threats, partly out of sympathy for the shooter, who’d become a populist cause célèbre, and partly because Walz’s post had alerted people to the fact—perhaps obvious in retrospect—that Citi Bikes were being tracked. If Walz could approximate the path of the shooter, could he stalk anyone’s ride? (In the end, Mangione turned out not to have used Citi Bike at all.) In response to the outcry, Citi Bike changed its A.P.I. so the data was no longer accessible in real time. Walz had undermined his own access to raw materials, but his project had already succeeded, in the way that art often does, at drawing attention to the overlooked. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com