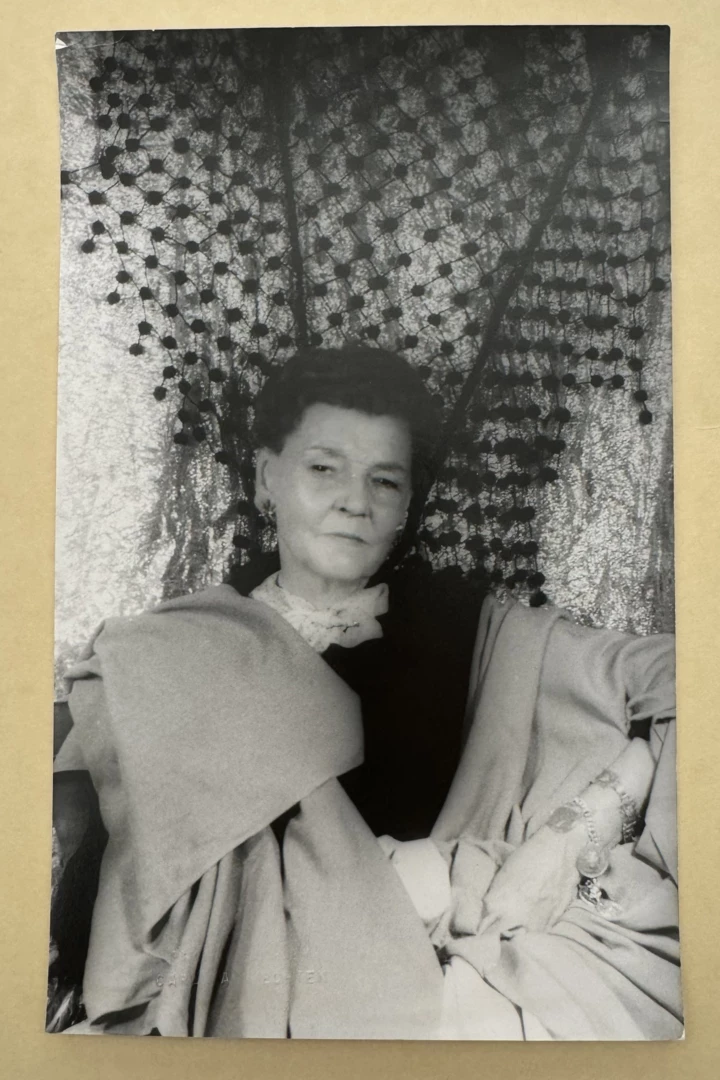

On the 3rd of June 1886, Kharkov gave birth to Varvara Karinska – a brilliant artist who encouraged Hollywood, won an Oscar for her costumes and started a revolution in light ballet. The ballet's predecessor, Katerina Yeletskikh, visited the archives of Varvara Karinska at the New York City Ballet, where the famous artist performed for over 30 roles.

Advertising.

The biography and creative paths of the Kharkiv woman Varvara Karinska recall a great novel: an Oscar for costumes for the film Joan of Arc (1949), a nomination for Hans Christian Andersen (1952), a match with style icons Hollywood and Broadway. Ale true khanny mystkini originally from Kharkov, who inspired the world, formerly ballet. On the birthday of the artist Varvara Karinska, we learn about her career in ballet, to which she dedicated more than 50 years of her life, setting standards that are still being deprived of standards in the whole world.

New York has its own mecca on the map – Lincoln Center. The Metropolitan Opera House, the School of American Ballet, the Library of Stage Mysteries of the New York Public Library and the New York City Ballet are located here. For NYCB, the Kharkiv Barbara herself, as they knew behind the cordon, but Madame Karinska created over 9,000 costumes, designed more than 75 ballets and actually shaped the visual DNA of the corpse.

Next to the campus there is a costume workshop: light, spacious rooms where artists, choreographers, designers, artists and designers work today. Here, rolls of fabrics are transformed into suits that sit near the bright spotlights.

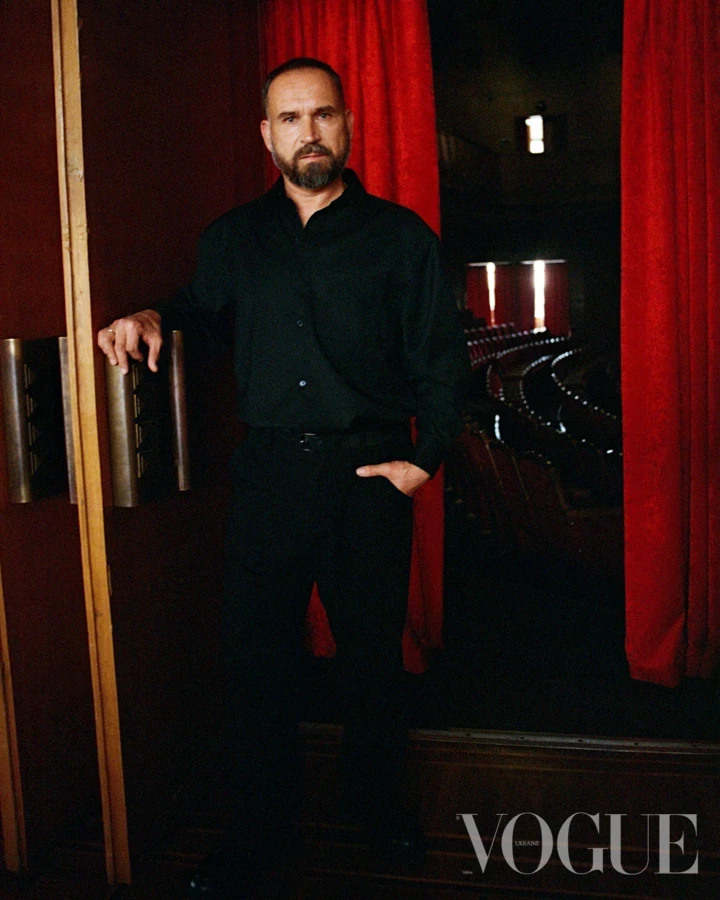

Of course, Madame Karinska did not work here – this master was opened approximately ten years after her death in 1983. During these hours, various factories were set up on 61st, 57th and 44th streets. And in the current costume shop they meticulously preserve their costumes, notes and sketches: here the same dark brown wardrobe stands outside her office, overlooking the photograph, and above the desk of NYCB costume director Mark Goeppel hangs a sketch with a signature Karinskaya.

“Vona was extremely important for Balanchine and the corpse – and is deprived of such a dosie,” like Mark Goeppel. “We save her work as it grows, and even if you look for a new idea, it is natural to go wild to the extreme. In my opinion, there created some of the most beautiful ballet costumes in the world.”

“I Shakespeare for literature – and Madame Karinska for costume”

When George Balanchine, co-founder of the New York City Ballet and a rich artistic director, was asked about the formula for his success, he uncompromisingly stated: “Fifty hundred years of the success of my ballets are the costumes.” Barbara Karinska.

Of course, the emergence of modern productions and choreography naturally influences costume design. The looker changes – the look changes. Part of the costume in the success of a production today is no longer as primordial as it was during the era of one of the most successful creative duos in the history of ballet – Balanchine and Karinska. “During Karinskaya’s time, the public often came to the premieres to marvel at what the designer had come up with,” adds Mark Goeppel.

“Shakespeare for literature – and Madame Karinska for costume,” said George Balanchine. Lincoln Kirstein, writer, philanthropist and co-founder of the New York City Ballet, noted with his colleagues how important Karinska was for Balanchine. Kirstein, lying down to those who do not give out compliments on impulse, proté Karinska, inspired by Leonardo da Vinci.

Varvara Karinska's first works associated with ballet date back to around 1916, when her first public exhibition took place. The same mistkina presented 12 “seamless” collages with ballet scenes. Already in 1933, in Paris, her dialogue with George Balanchine began: Karinska creates costumes for the short-haired troupe of the Ballet de Monte Carlo. As an independent author of images before ballets, Balanchine declared herself in 1949. And in 1963, following a then record-breaking grant from the Ford Foundation to support ballet, the theater re-founded its own costume department under the direction of Karinska.

Madame Karinska gave the choreographer a lot of freedom

“Balanchine became a great choreographer, without any work. The design and design of the costume greatly influence the way the dance is performed and the way the dancers collapse. Zustrich from Barbara Karinska on the beginning of his career and then the combinations became fundamental for Balanchine,” says Linda Murray, curator of Viddle’s dance. Jerome Robbins's intercession with the collection and research of the New York Public Library (stage mysteries).

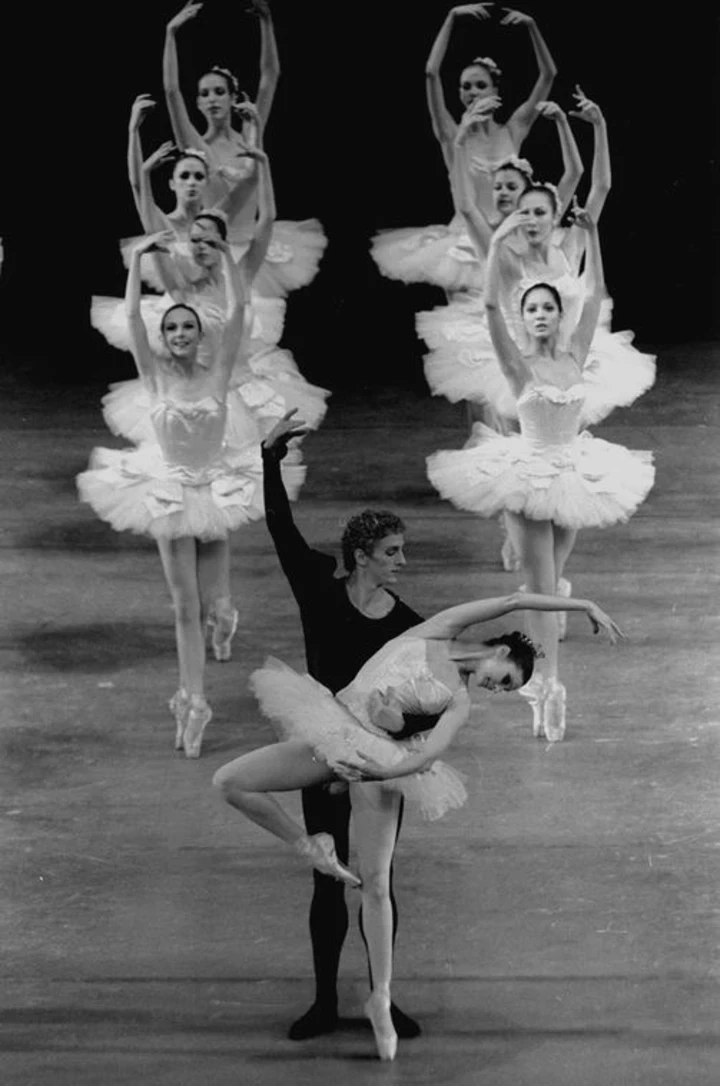

Among the numerous innovations of Varvara Karinska is the reconstruction of the ballet tutu. There are three main silhouettes: classic – flat, most visible; shopenka – romantic, long-lasting and flying; crotch – this is the name of the bun tutu (bell tutu). Karinska created a version called powder-puff tutu – which is in between the classic and bell tutu.

The tutu that Karinska created with her team for Balanchine’s ballet “Symphony in C” has become a true engineering diva. There will be a silhouette and, smut, work on the back of the lungs, allowing the dancers to collapse more and more precisely. The lines of the body become natural, without the “cropping” effect. For Balanchine's technique – with its fluidity and great ensembles – there was a whole principle. Karinska took away the metal frame from the pack, cut out a number of tulle balls and mesh – and created a rumored shape that collapses simultaneously from the dancer’s body. Photo 20

The phenomenon of Karinskaya is related to the brave person with the materials. She mixed fabrics of different textures, which were often not considered “danceable”: she combined luxury seam satins and thin seam tulles with simple, seemingly utilitarian bases. In one of the ballets, the decor was made from horse hair – the cheapest material, which in her hands acquired a noble sound.

What is Karinska’s secret: the “invisible” beauty of couture. Oblyamivka with the cheapest prices, which, according to all the rules, would be difficult to deal with in the middle, turned out to be the best for her. There is real magic – under the lining: miniature bows, frivolous folds, clashing colors, weird knots and attached details that you can’t see from the first row, then the stench “revive” the costume in a dynamic way. Karinska followed the principle: those who are not visible are so important.

Karinska rose, she actually “painted” the scene. In a dance, the scenery is often different, so the lighting designer and the costume designer can work together to create the middle ground. Often Karinska herself shaped the costumes into these trivial textures to ensure the decoration.

Karinska’s design “revolution” manifested itself in her famous selection of colors. In the La Valse ballet, for example, the top balls of the romantic tutu were voluminous gray, and underneath them were the orange and erysipelas that “wobbled” in Russia.

“We are infected with other fabrics and other chemistry of barberries: the openings, expanded in the 1950s–60s, are now inaccessible or blocked,” explains Mark Goeppel. “But we save the principles: sharing colors and clarity, lining with a different shade to eliminate the required vibration in the light.”

Woman “rob” business

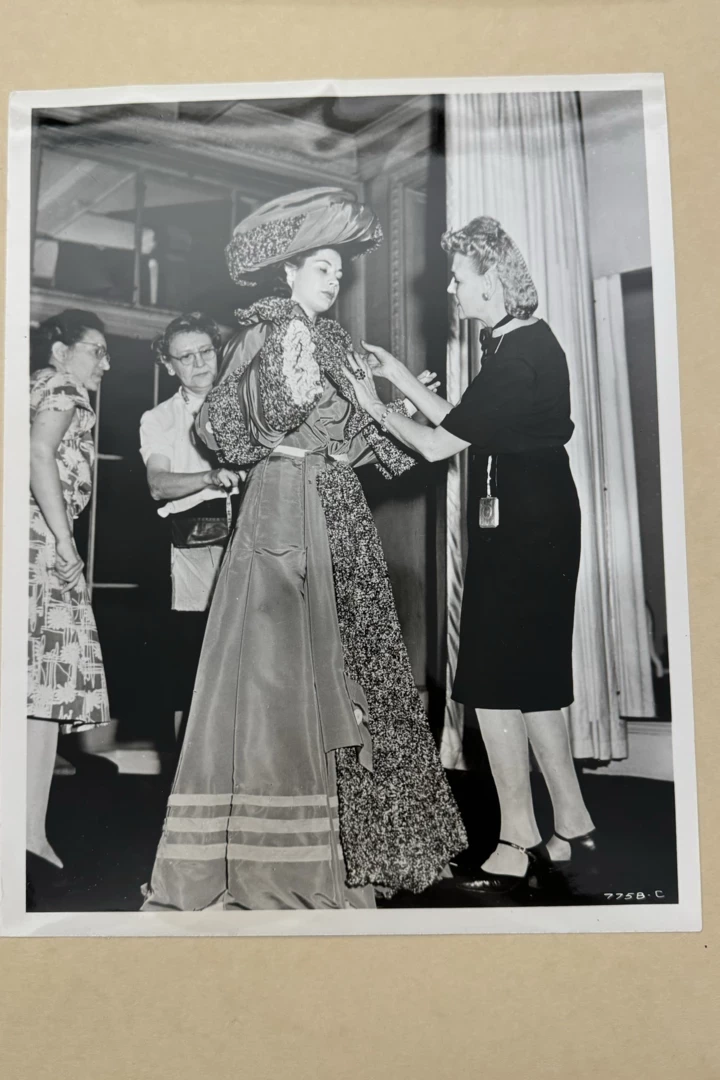

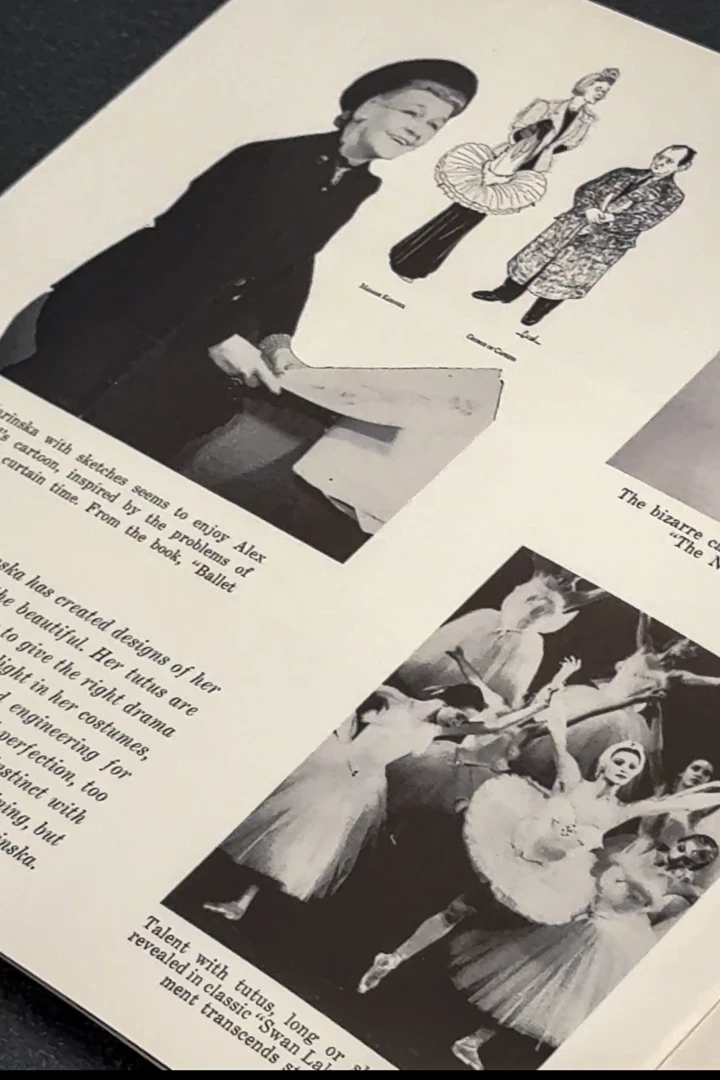

The creativity of Varvara Karinska took place in those hours when women’s rights became the subject of heated discussions. Vaughn was quick to remember the moment: her career was not as “a piece of work for a man-designer,” but as an independent author, which meant how ballet stands on stage. Photo 17

Thus, having been the daughter of the Kharkov merchant-millionaire Andriy Zhmudsky, Varvara did not know from childhood what poverty was, even before the revolution dared to deprive Russia of it. And we know the story of how Karinska exported valuables, stored under cover and from the chosen ones, trying to steal away a part of her homeland – and, according to evidence, significant peace was lost to her. She, having moved first to Europe, and then to America, no longer recalled the prosperity that she knew in childhood. I happened to become an entrepreneur: my job and income supported my family.

The scale of power, character and efficiency is most clearly illustrated by the story of the London premiere of Mikhail Fokine's Don Juan in 1936. One of the newspapers wrote: “The lead heroine of Fokine’s new ballet “Don Giovanni” did not appear on the stage of the theater on the opening night. This is Madame Kavinsky (as they called Karinska), who altered all the costumes in nine days And nights after they were destitute by the fire. The Kravchins worked for twenty-four years in order to catch up, and some of the costumes were brought by taxi twenty hours before the curtain rose.”

When Karinska's suits turned home

On June 22, 1962, Karinska received one of the key awards in the field of dance – the Capezio Dance Award. Without exaggeration, this was the pinnacle of professional recognition, and at the same time an important gesture: the city meant not less than the ballet’s contributions, but a wider stage presence. Varvara became the first laureate without being a dancer, and with the title she received a check for 1000 dollars.

In addition, the costumes of the Ukraine came out during the Kiev tour of the New York City Ballet. On November 13, 1962, the corpse performed on the stage of the Kiev Opera. That evening the public enjoyed the so-called visits of one of the most progressive ballet companies – “Waltz”, “Blisque Alegro”, “Fanfari” and “Symphony in C Major”. Photo10,11,12,13

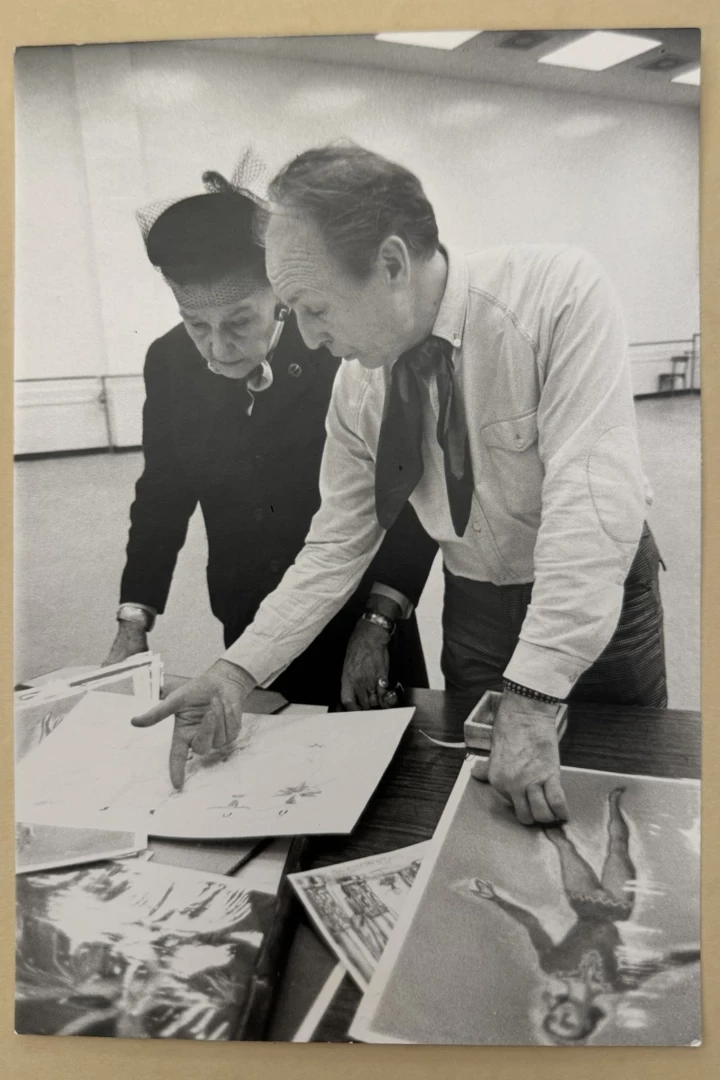

Karinska was never “just an artist.” Their collaboration with Balanchine has quickly grown into a permanent partnership: it will require a powerful workshop – people, equipment, materials. After many important projects, Balanchine has secured our minds: in fact, I will close the Kravetska costume department, so that it could create suits of the “necessary level” for the new ones and in the required duties. Before the skin ballet, Karinska prepared full-scale renderings: sketches with a modified silhouette, samples of drapery and reporting notes, so that Balanchine would highlight the idea. Up to the skin arch, she attached the clasps of the very same fabrics that she planned to use. Decisions about the “look” of ballets were praised in close tandem. Their thought was valued. Photo 14.15

“I think it will forever be a key part of the light ballet of the New York City Ballet – no matter how many new ballets we create and how many new designs appear,” says Mark Goeppel. “This is the “outer stone” company. I don’t think there’s any way to obscure Karinskaya’s slaughter. Regardless of how well people know her, they recognize her work. design of dance costumes, May turn to Barbara Karinska.”

Text: Katerina Yeletskikh, author of the You-Tube channel Ballet Maniac

The author would like to thank Linda Murray, curator of Weddell Dance, for assistance in preparing the material. Jerome Robbins, Advocate Director of the Collection and Research of the New York Public Library of Stage Mysteries; Mark Goeppel, Costume Director, New York City Ballet