Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

She has presented us with all, save for her visage. Meaning, she’s gifted us with everything and nothingness. “Masked Nude, Harlem NY,” a monochrome image from 1999, stands as a work as paradoxical as its title infers. A Black woman rests on a divan. Her exposed extremities hang freely over the plush material, her groin area barely veiled. She is posed akin to the subjects of Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Gustave Courbet. Yet, this woman would never have served as their model. She’s been captured by Coreen Simpson, a Black woman artist of the twentieth century, contemplating twentieth-century themes. Simpson—a photographer, a designer of jewels, and an author—fundamentally chronicles trends. For decades, she has scoured the city’s upper and lower regions to grasp who people are by immortalizing how they wish to appear. Or not appear: by offering us bodies without countenances, Simpson delves into a species of anti-portraiture. She reinvents, through her masked-nude photos, the Black woman as an emblem of concealment.

“Masked Nude, Harlem,” 1999.

“The face did not carry weight within the legacy of nude photography,” Simpson remarked in a recent discourse. And what apparatus has Simpson utilized to shadow the faces of those within her photographs? That mask we refer to as “African,” a term almost devoid of meaning. One of the concepts Simpson appears to be exploring in her masked-nude assortment, as I see it, is the friction amidst the commercial and the sacred. In the early nineteen-nineties, Simpson, by then a photographer for periodicals whose artistry had graced Vogue, the Village Voice, Unique NY, and other renowned style publications, had broadened her endeavors within the fine-art sphere, depicting models as pinups—Jet Beauty of the Week stances—and then neutralizing their vulnerability with those masks. The masks evoke not necessarily the authenticity of the homeland, but rather those of uptown shops, in which they, or replications of the genuine article, are retailed. And thus, we observe the nudes through thrilling, layered sentiments, sentiments that surpass simplified concepts of reverence and celebration of the woman historically slandered in visual culture.

“Black Girl with Eye,” 1991 / 2021.

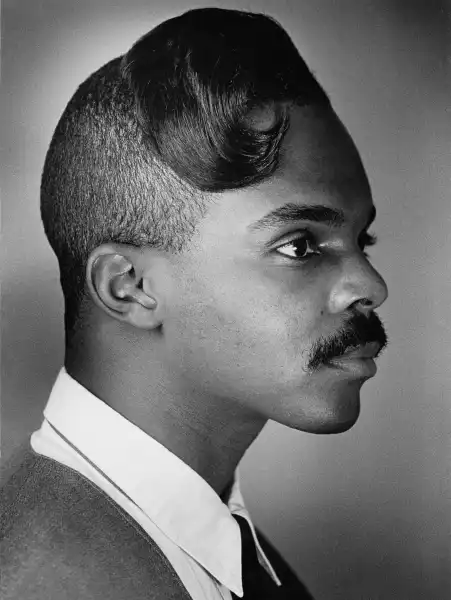

“Man with Curl,” ca. 1990s.

I encountered Simpson’s series in 2022, at Fotografiska, situated in New York. The Nigerian British curator Aindrea Emelife had masterminded an exposition set to traverse the diaspora, titled “Black Venus.” Upon entering, one perceived that the Enlightenment and its duplicity, its classification of races, were under attack. Archival materials hailing from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries positioned the present-day specimens, each culled from between the nineteen-seventies and now, as rejoinders to three age-old Venuses: the Sable Venus, the Hottentot Venus, and Josephine Baker personified as a harlot. Parallel to Simpson’s masked women, Emelife had assembled artworks by Renée Cox, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Kara Walker, Mickalene Thomas, Widline Cadet, Ming Smith, and a host of others. Coreen Simpson’s images resonated deeply with me, partially given that I had not previously seen them yet felt I knew them intimately.

“Toni Morrison,” 1978.

“Ming Smith, New York,” 1983.

“Dr. Nina Simone,” ca. 1991.

Is it owed to her erotic expression residing in such intimate converse with street jargon? Is it owed to her candid renderings of human yearning and distinction recalling Diane Arbus? One senses, within the presence of her efforts, a lack of expanse separating the lensman and her subject matter, despite her best anonymizing attempts. One longed, while traversing the show, for Simpson to have seized the chance to capture that supposed harlot, the iconic Baker. They embodied the sort of women grasping the prowess of disguise. What choices would she have executed with the woman donning her brown complexion yet navigating a perilous existence steeped in political subterfuge, one who exploited the French affection for Black figures, who recognized the safeguard that masks deliver to the soul? I yearned to delve deeper into Simpson and her apparent connection to both witnessing and evading sight. It startled me to realize Simpson’s desertion by her parents, who, together, embodied the antithetical poles of classic New York cultural divergence: a Jewish pedagogue mother, a Black jazzman father. I found it unexpected that Simpson held as her iconic figure of beauty her childhood social steward, a woman of ebony complexion named Miss Foster. I held no surprise in discovering Simpson had dabbled in modelling, owing to her beauty, but I pondered how her time before the camera could have sculpted her ethos guiding its lens.

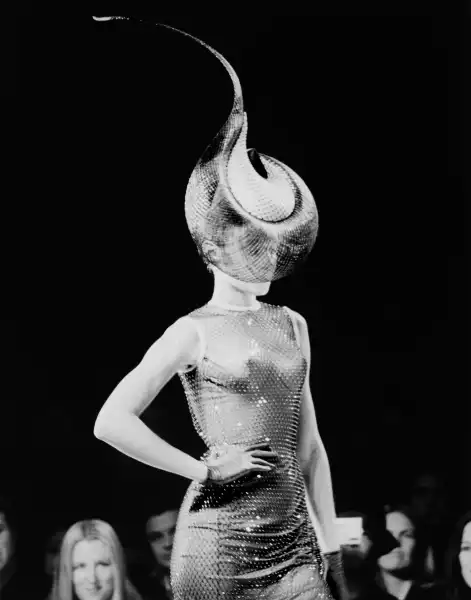

“Unknown Model Wearing a Philip Treacy Hat,” 1989.

“Untitled,” 1979.

Simpson, interestingly, once circulated a personal doctrine. Senga Nengudi and Charles Abramson, the architects of “Joining Forces: 1+1=3,” a 1986 showcase at the New Muse Community Museum, in Brooklyn, and Gallery 1199, within Manhattan, commissioned Simpson to capture portraits of their featured artists, organized into hetero pairs for a cooperative exploration. Within the exposition text, Simpson relays the experience of visitations by various spirits during her photographic endeavors: the “Spirit of Anger,” the juxtaposed spirits of “Mystery and Metaphysics.” It is the “Vulnerability” spirit which we might contemplate, far from trivial. Simpson details: “She dislikes the world’s gaze, and the others feigned ignorance of her identity, but she disregarded their actions, embodying one of the most compelling spirits.” Our connection between photography and revelation is almost reflexive. Her opus feels accessible, enriched with charisma, yet Simpson concurrently records what it signifies to veil. She grants us insight into her subjects, yet we are denied a deeper understanding of them.

“City People,” 1976.

The masked nude is a vivid mosaic. Simpson stands as a remarkable polymath; having mastered one format, she feels spurred to embrace another. She adopts surrealism within her layered portraiture, fantasies echoing Man Ray and Romare Bearden, perceiving the human form as a raw material. The playwright Ntozake Shange, with her visage substituted with a grand, exquisitely textured mouth. A glamorous shot of a man, his coiffure styled into a foppish curve, with metal supplanting his features. These modifications imply the corporeal existence of the lensman herself, imposing her identity upon the visual.

“Ntozake Shange,” 1997 / 2021.

Simpson might have scaled the heights of success beyond photography, but she never abandons the realm of the portrait. The pieces within her Black Cameo Collection, Simpson’s jewelry line showcasing figures in silhouette, carved in high relief, have graced the presence of the most eminent and glamorous women, Black and white alike. The cameos could be interpreted as objects conveying a rebellion against Victorian tenets. (Who produced the fortunes that adorned the bejewelled ladies of the British Empire?) The woman depicted in profile across Simpson’s cameo pieces is a Black woman displaying dark hair. She is entirely face, yet remains unfamiliar to us. She, too, is another Venus.

“Gail Pilgrim wearing a Black Cameo Collection crown,” 1990s.

These photos and the text are extracted from “Coreen Simpson: A Monograph,” published under the Aperture imprint.

Sourse: newyorker.com