Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

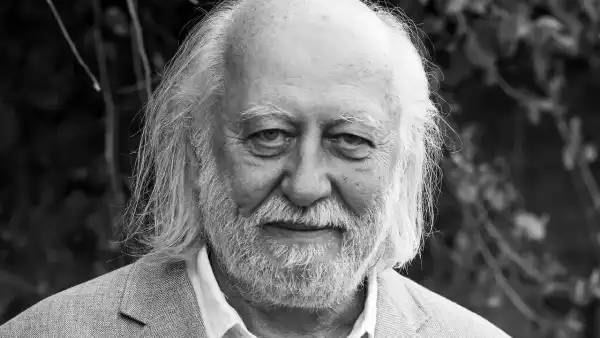

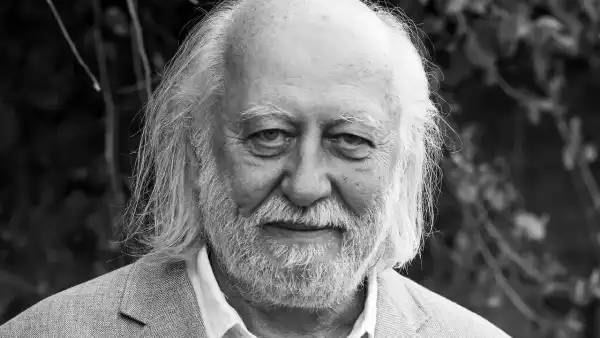

Back in 2011, I observed that experiencing László Krasznahorkai “is akin to observing individuals gathered in a circle on a city plaza, ostensibly warming their hands at a blaze, only to realize, upon drawing nearer, that there exists no fire, and that they are assembled around absolutely nothing.” For numerous average readers, the notion of stepping into a fictional realm perpetually oscillating on the precipice of a revelation that remains perpetually forthcoming but obscured, in which words circulate incessantly around reference, and whose preferred instrument is the extended, unbroken sentence, one that might span, for instance, four hundred pages to unfold, could constitute—well, it could constitute precisely the sort of wavering derangement that Krasznahorkai has depicted so skillfully and empathetically, for such an extended duration. It might embody what he has termed “reality scrutinized to the brink of lunacy.”

At that time, merely a pair of Krasznahorkai’s narratives were obtainable in English—“The Melancholy of Resistance” and “War and War,” which had seen publication in Hungarian in 1989 and 1999, respectively. Krasznahorkai already represented a European sensation, notably in Germany, where he resided and where the majority of his oeuvre had undergone translation. There, it was commonplace to perceive him as a potential future Nobel recipient, yet, with such scant material accessible in English, such pronouncements carried the weight of courtly tittle-tattle. Nevertheless, “The Melancholy of Resistance” circulated in the manner of exceptional underground literature. It possessed Hungarian origins; it boasted a magnificent, mournfully verbose title (subtly alluding to both the significance of resistance and its unavoidable depletion); and it garnered accolades from W. G. Sebald and Susan Sontag.

Aside from the two rendered volumes, there existed tantalizing glimpses of alternative works. Krasznahorkai’s introductory novel, “Sátántangó,” dating from 1985, remained untranslated into English, but one retained the option of viewing Béla Tarr’s seven-hour film adaptation of the same name, sourced from the novel. (Krasznahorkai has authored scripts for six of Tarr’s productions.) I had sampled approximately two hours of “Sátántangó” but, until the English rendition, courtesy of the poet George Szirtes, eventually materialized, I could solely envision the coiled yet perspicuous run-on sentences that Tarr’s protracted tracking shots were apparently exerting their cinematic utmost to emulate:

The doctor was seated adjacent to the window, enveloped in melancholy, his shoulder pressed against the chilly, humid wall, and he was not even required to alter his head’s position to observe the estate through the aperture between the grimy floral curtain inherited from his mother and the decaying window frame; rather, he needed only to elevate his gaze from his book, casting a fleeting glance to register the slightest alteration, and should it occasionally transpire—for instance, if he were entirely submerged in contemplation or because he had concentrated on one of the most remote features of the estate—that his eyes overlooked something, his exceptionally acute ears promptly offered assistance, though it was infrequent for him to be lost in thought and even more uncommon for him to arise in his fur-collared winter coat from the heavily padded, stuffed armchair—its placement precisely dictated by the accumulated wisdom of his daily routines, effectively diminishing to a minimum the number of potential instances wherein he would be compelled to relinquish his observational station adjacent to the window.

Anglophone audiences were commencing to catch up, as a deluge of remarkable creations surfaced in translation, validating Krasznahorkai’s brilliance: “Seiobo There Below” (2013), “Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming” (2019), and, most lately, “Herscht 07769” (2024), conceivably the most approachable of his narratives. (All of the recent narratives have been conveyed in a flowing, serpentine English by the exceptional Canadian translator Ottilie Mulzet.) Each represents a singular and unparalleled composition, and each broadens Krasznahorkai’s spectrum. “Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming,” for instance, orchestrates a tragicomic, idealistic confrontation between the disheartened and xenophobic inhabitants of a rundown provincial Hungarian settlement and a returning émigré nobleman, the Baron Béla Wenckheim of the title, in whom they have invested their (frequently reactionary) aspirations. However, the returning aristocrat emerges as a worn-out profligate, destined to discover no sanctuary or absolution amidst his bickering and inbred compatriots. The narrative serves as a reminder of Krasznahorkai’s capacity for humor. “Eternity—will persist for as long as it persists” constitutes the narrative’s amusing epigraph.

Nonetheless, in certain respects, those initial pair of narratives that I perused in 2011 delineate the distinctive ambiance prevalent in much of the subsequent work: the volatile politics of diminutive towns in Hungary and the former East Germany (nativists, neo-Nazis, proponents of law and order); an unsettling premonition of impending doom, both political and metaphysical; and Krasznahorkai’s predilection for visionary obsessives and holy innocents (a global expert on mosses, an archivist convinced of the discovery of a long-unremembered manuscript who journeys to New York to disseminate its existence, a pianist fixated on the well-tempered tuning of the piano). Despite outward appearances to the contrary—the meandering sentences, the impassioned intellection—there exists nothing impenetrable within Krasznahorkai’s body of work, both vintage and contemporary, which squarely confronts current European actuality and its inherent perils, encompassing the agonizing dynamics of settlement, movement, and identity.

For prospective readers, all of this might be optimally encountered within Krasznahorkai’s most recent narrative, “Herscht 07769,” concerning an outsized yet, in his own manner, perfectly commonplace individual, Florian Herscht, who resides in a diminutive town in Thuringia, situated in the former East Germany, and whose occupation involves scrubbing graffiti from the town’s civic structures. Herscht resembles a galvanizing yet perplexed fusion of Saul Bellow’s Herzog, Thomas Bernhard’s Wertheimer, and Hanta, the reclusive narrator of Bohumil Hrabal’s narrative “Too Loud a Solitude” (1976), whose function consists of compacting wastepaper and archaic tomes. Herscht has embraced the notion that an accumulation of antimatter will somehow precipitate the world’s demise, and he resolves that the individual best equipped to address his apprehensions is the German Chancellor (and erstwhile physicist and quantum chemist) Angela Merkel. To her, he initiates the composition of lengthy epistles that proceed profoundly unanswered, bearing his surname and postal code: Herscht 07769.

Bellow, predictably, secured the Nobel Prize in 1976; Bernhard and Hrabal ought to have attained it. Nevertheless, the Academy, at a minimum, rectified matters with Krasznahorkai. May his accolade usher in an influx of readership. For those of us already immersed within the peculiar and wondrous sphere of his narrative creations, the revelation of his triumph in this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature presents no considerable astonishment. Indeed, it manifests as something manifestly equitable, akin to a richly deserved libation at the conclusion of a day’s strenuous labor. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com