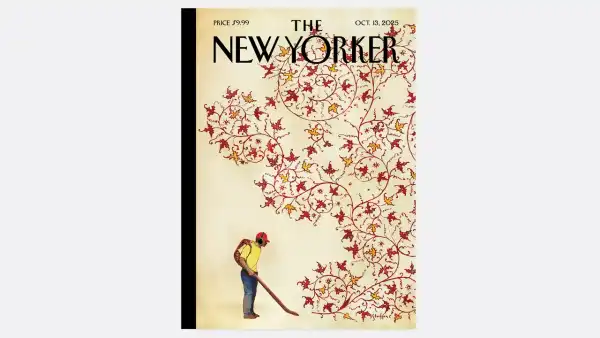

Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

“It was simply foolish,” the lensman Jeremiah M. Murphy shares with me. “I maintain rules, and I disregarded one of them.” Murph, as he’s known among acquaintances, is recalling a mishap during a wild-horse competition some years back at the Rosebud Wacipi, Fair & Rodeo, situated in South Dakota.

A wild-horse competition represents one of those athletic contests that’s difficult to fathom ever having been created, let alone existing in the era of liability claims. The objective is to equip and mount untrained horses as rapidly as feasible, typically within two minutes, and its particular insanity derives from the fact that groups of cowboys, a half-dozen or more, participate concurrently. This entails that roughly twenty to thirty individuals are active within the arena in groupings of three, grappling with horses at once: the shanker grasps a tether to control the horse, or at minimum impede its movement; the mugger seizes the horse’s head to avert it from rising on its hind legs; if those two are fortunate enough to nearly achieve their objectives, then the rider hurls a quick-cinch saddle onto the horse’s back, attempts to climb aboard, and then sprints for the finish line.

Red Scaffold Rodeo, South Dakota, 2016.

Murphy estimates the lifelong-injury frequency among wild-horse participants is at a hundred per cent, and it could be just about that substantial for the event’s photographers. He personally averted wounds for some years via adherence to a firm guideline: “When the initial horse frees itself, I advance to the fencing.” However, subsequently, in Rosebud, “the unfolding action was so compelling that I sustained my pursuit. I was crouched on one knee, with my leg extended, anticipating this horse to rear, and I was confident it would. A dusty sun was present, and I simply knew it would yield an excellent image,” Murphy recounted. “And, promptly, a bullfighter was extracting me by my belt.” He could hardly ambulate, and by the point at which he transported his fractured pelvis to the emergency department, the attending physicians could solely “provide me with a set of crutches and a supply of analgesics.”

Crow Fair and Rodeo, Montana, 2014.

Upon viewing Murphy’s wild-horse-competition snapshot originating from Rosebud, it’s challenging not to sense that any discomfort held value. Echoing a black-and-white Bruegel set against a Badlands-esque backdrop, the depiction is replete with elements: horse rearing, men recoiling, headwear aloft, footwear dragging, and hooves pounding. Intriguingly, it even encapsulates sensory impressions it ostensibly cannot, spanning the din of clanging chutes alongside slamming portals to the tang of blood joined with grime and the fragrance of tobacco emissions and bovine excrement. Baseball serves as America’s leisure pursuit and football its foremost sport, though rodeo might as well embody America itself: cowboys collaborating with clowns, raw valor coupled with outright absurdity, an enduring power struggle between sincerity and spectacle, myth and actuality. Murphy possesses intimate knowledge of rodeo’s paradoxes, and, for this reason, throughout the past fifteen years, amid the country’s patriotic fabric unraveling, he has committed substantial time to documenting these happenings and assembling the compendium he designates “Indian Rodeo.”

Owl Bonnet Rough Stock Rodeo, 2023.

Oglala Lakota Nation Fair and Rodeo, Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 2016.

Rosebud Rodeo, 2015.

Murphy’s place of birth was Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and he has resided for the majority of his existence in Rapid City. Professionally, he is a lobbyist, akin to his progenitor and a paternal grandparent, and the spectrum of his clientele over time is as extensive as Warren Buffett’s holdings: encompassing liquor merchants, gaming affiliations, and tobacco corporations, in addition to a teachers’ collective and a medical center. Presently at sixty-seven, he retains a measure of contentment in lobbying yet aspires to early retirement to dedicate himself wholly to photography.

His engagement with cameras extends to his early years. His father possessed a Mamiyaflex camera, and the younger Murphy developed an affinity the initial instance he peered through its waist-level viewfinder. Subsequently, his parents gifted him a compact 35-mm camera for Christmas; by his late teenage years, he had independently grasped composition by snapping pictures of bands within local drinking establishments, where, absent sufficient illumination for autofocus, each shot became an exercise of iterative refinement. He departed South Dakota for higher education in Nebraska, before spontaneously relocating to Los Angeles, where the drinking venues and performing bands were superior, and wherein, due to a limited capacity to procure film, he guaranteed the enhancement of his photographic skills.

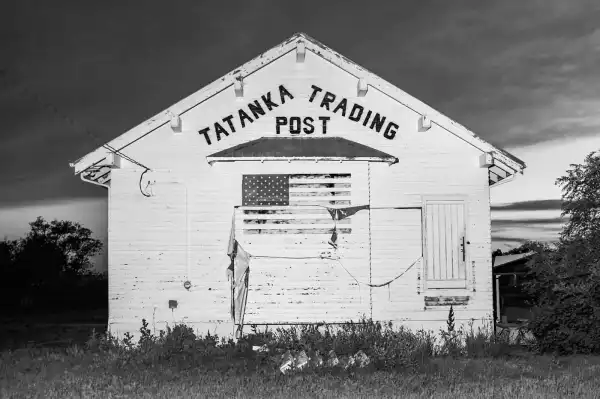

Scenic, South Dakota, 2014.

Rosebud Rodeo, 2015.

Subsequent to marrying and fathering three offspring, he relinquished his involvement within the music milieu; subsequent to embracing recovery, he similarly abandoned drinking venues. He briefly ceased photographic activity altogether, yet subsequently unearthed an unconventional avenue into sports photography: the peripheries of his progeny’s athletic competitions. “Soccer imparted that predictability is absent within the field. I mean, on multiple instances, I’d assure a parent, ‘I obtained an outstanding image depicting your child in a particular action,’ and upon arriving home and projecting it onto a substantial display, the purportedly exceptional shot lacked focus. This bears a resemblance to rodeo—the genuine outcome perpetually evades certainty.”

Big River’s Bronc Fiesta, Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 2025.

Murphy’s inaugural rodeo photographic undertaking was unplanned. He casually encountered the Crazy Horse Stampede Rodeo situated in the Black Hills. “I virtually drifted in there, on Friday, during its designation as Indian Rodeo Day, and I simply perceived it as utterly wondrous. I reflected, I’ve dwelled here for my duration of life and remained unaware. It induced a degree of embarrassment.” He bore his photographic apparatus, and was taken aback by the extent of proximity granted to him. Later that summer period, he endeavored to surreptitiously position himself behind the chutes to capture images at the Days of ’76 Rodeo, in Deadwood, until an official discreetly touched his shoulder. Murphy anticipated the man’s imminent request for a press accreditation, yet instead received notification that his ball cap coupled with his golfing shirt were insufficiently evocative of cowboy aesthetics; he necessitated securing a Western-style garment or vacating. “I was recounting that anecdote to a seasoned bullfighter,” Murphy recalls, “and I inquired whether the imposition of a dress code was customary, and he averred, ‘No, those denizens of Deadwood possess an inflated sense of self-importance’—akin to an environment mirroring Fifth Avenue or Rodeo Drive.”

Owl Bonnet Rough Stock Rodeo, St. Francis, South Dakota, 2023.

The South Dakota legislature convenes solely during three months of the annum, spanning January through March, and despite the scheduling of summer deliberations, Murphy commits numerous weekends commencing Memorial Day and concluding Labor Day journeying an hour or dual or treble to pursue rodeos situated within the western segment of the state. He ventures forth as frequently as practicable equipped with his Nikon D600 coupled with D750, proceeding wherever Facebook promulgates imminent dynamic activity. There exist approximately a thousand sanctioned rodeos recurring annually nationwide—the professional echelon can extend million-dollar reward allocations—however, significantly more diminutive rodeos manifest weekly on familial ranches, 4-H exhibition grounds, or tribal domains. These can bear resemblance to primitive rodeos, comprising casual rivalries among ranch laborers, who even post protracted workdays devoted to branding or herding cattle couldn’t resist showcasing prowess. Murphy necessitated several years to ascertain bearings, cultivating a proclivity for the cohesive, resilient Indian-rodeo grouping, gradually familiarizing himself with the athletes alongside the spectators of rodeos in locales spanning Eagle Butte, Pine Ridge, Red Scaffold, Rosebud, and St. Francis.

Dupree Pioneer Days Rodeo, South Dakota, 2016.

Any photographic artist operating throughout the American West, notably one documenting native communities, functions amidst the intricate shadow cast by the turn-of-the-century ethnographer Edward Curtis, celebrated for his extensive chronicle of tribal existence, yet occasionally critiqued for the theatrical methodologies alongside the sentimental resonance within his twenty-volume opus “The North American Indian.” Murphy, conversely, perceives himself as an outsider harboring a vigilant and inquisitive perspective, and he admires the insight conveyed by Robert Frank within “The Americans.” He similarly cherishes the majority of Weegee’s productions, notably the characters and caricatures, though he would never propagate an image depicting an individual rendered defenseless or damaged. His sensibility of humor manifests within the manner he centers bull-riding vests emblazoned with inscriptions such as “Ridin’ Dirty” alongside “STRAIGHT OUTTA RIDGE,” the dispensation of an image capturing a cowboy extending dual middle fingers, and the proficiency demonstrated in capturing comic-book-esque skids joined by dust devils, imploring sound depictions alongside conversational bubbles—WHAM! SPLAT! THUD!

Sourse: newyorker.com