Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

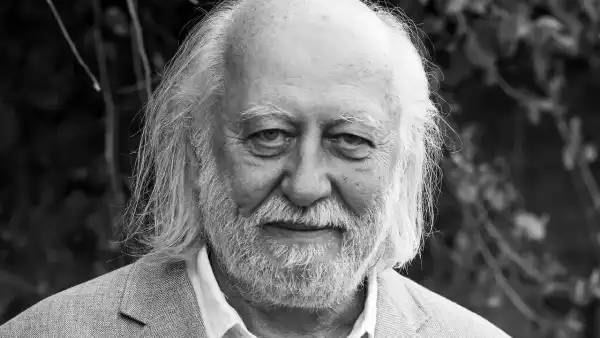

The Jagdish Photo Studio in Manori appeared to Ketaki Sheth as a kind of apparition. A photographer from Mumbai, Sheth owns a home in the coastal village, about a sixty-kilometre drive north of the city, and had made innumerable visits there without ever knowing of the studio’s existence. One afternoon in 2014, she was out taking pictures on a Leica M9 when she came upon the business, wedged between an old grain shop and a hardware store—“a fairly nondescript little space,” as Sheth put it recently. An employee manning the front desk explained that it was the only place in the area for customers to have photos taken for their Aadhaar cards, biometric I.D.s issued to almost all of India’s adult population. Sometimes, the employee mentioned, people came for portraits to mark special occasions or holidays. Sheth’s interest was piqued. “Are you expecting people today?” she asked.

Studio 786. Cuttack, Odisha, 2016.

Jagdish became the first of more than sixty-five studios across the country that Sheth would photograph over the next three years. The resulting series, “Photo Studio,” later published by Photoink as a book of the same name, was a departure from the black-and-white, analog documentary style that she’d employed on previous projects, including images of the streets of Mumbai as well as visual ethnographies of twins and of the Siddis, an Afro-Indian ethnic group.

Babas Studio. Trivandrum, Kerala, 2016.

The portrait workshops, she decided, called for a more vivacious treatment: for the first time, Sheth shot in color. The vibrancy of her photos stood in contrast to the businesses’ fading role in Indian life. In the era of the smartphone, formal portraiture had gone out of fashion, and studios like the one in Manori were on the verge of closing down. Sheth told me, “Either a road was being widened, and the government was giving the owner compensation to get out, or a developer was coming in to build.” Most of the sons and daughters of the proprietors who remained had little interest in continuing their parents’ line of work. One owner, in Hyderabad, had lost the painter of his ornate backdrops to a patron in the Middle East. But some of the sites Sheth visited betrayed traces of a shimmering heyday. Shelves were still lined with reams of photo records and old boxes of Fujifilm printing paper. A studio in Mumbai retained the tungsten lamps that once provided the lighting for portraits of Hindi cinema’s most venerated stars.

Thara Studio. Ramanathukara, Kerala, 2016.

Victory Photo Centre. Hyderabad, Telangana, 2016.

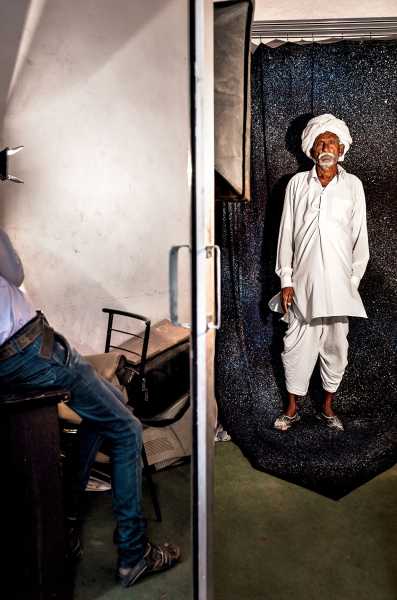

Krishna Digital Photo Studio. Jaipur, Rajasthan, 2016.

Thara Studio. Ramanattukara, Kerala, 2016.

Moti Art Studio. Ajmer, Rajasthan, 2016.

In each city, Sheth asked locals to pose amid the trappings of this disappearing world. Many of today’s studio photographers favor the ease of Photoshop: newlyweds who come in for wedding pictures can choose to be digitally transposed in front of the Eiffel Tower, the Taj Mahal, or Egyptian pyramids. But occasionally Sheth found delicate hand-painted backdrops stashed away in storage and put them to use. (A few newer studios, she learned, had outsourced the effort to a company in Punjab that specializes in mass-producing painted backdrops on canvas.)

Jagdish Photo Studio. Manori, Maharashtra, 2015.

Thara Studio. Ramanathukara, Kerala, 2016.

Babas Studio. Trivandrum, Kerala, 2016.

Sitaram Digital Studio. Bhavnagar, Gujarat, 2016.

Jagdish Photo Studio. Manori, Maharashtra, 2015.

In Sheth’s images, the subjects’ backgrounds appear almost as dreamscapes, or portals to distant universes. In Kerala, two brooding boys lie in front of a placid, cerulean lake, with a snowcapped mountain range in the distance. Behind two Manori women in hijabs is an Ionic column reminiscent of an ancient Greek temple. A Rajasthani farmer poses in front of a sequinned curtain that brings to mind a glittering galaxy of stars. Other shots focus on the businesses’ peeling interiors or their obsolete props and tools: a cutout of Mahatma Gandhi, the oldest tripod that Sheth had ever seen. Her work—which was featured in a recent exhibition, “Staged,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art—not only pays homage to India’s photo studios but also calls up the œuvres of vernacular portrait photographers, such as Mike Disfarmer and Seydou Keïta, who elevated their everyday outputs to art.

Phototec Studio. Calicut, Kerala, 2016.

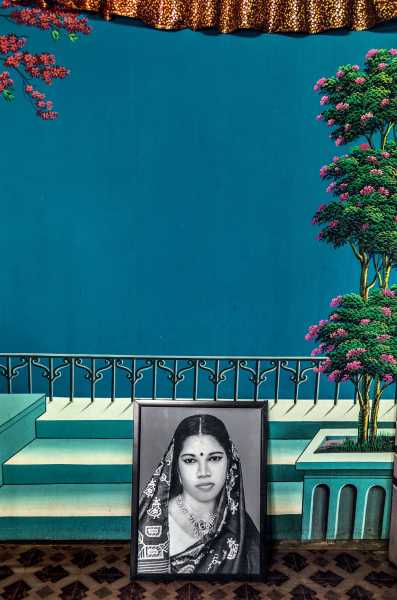

While trawling through the shelves of a studio in Odisha, in eastern India, Sheth spotted a black-and-white photograph hanging on a wall. It was a portrait of the owner’s late mother as a young woman, her neck adorned with an intricate pendant. “Would you mind bringing her down?” Sheth asked. She created a makeshift shrine, placing the framed image in front of a painted backdrop that shows a balcony overlooking a blue expanse of sky, evocative of a heavenly afterlife. In other ways, too, Sheth’s project became a way to honor previous generations. At Vanguard Studios, in Mumbai, Sheth came upon drawers full of glass negatives, receptacles for the countless unnamed sitters who’d once patronized the establishment. Photographs of such ephemera are interspersed throughout her book. In a caption for one negative of a couple posing in formal attire—the husband in a boxy fifties suit, the wife in a sari—Sheth writes, “Do their grandchildren know that they still exist on glass?”

Singh Studio. Anandpur, Odisha, 2016.

Sourse: newyorker.com