Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

When the photographer Víctor Zea was a child living in Lima, Peru, he was taught an Inca myth of origin. First there was the sun god, Inti, and before civilization there were his children Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo. The pair emerged from Lake Titicaca carrying a gold staff that would, Inti assured them, sink into the earth only when they had reached their final destination. The scepter pierced the ground of the Huanacaure mountain, and so rose the glimmering empire of Cuzco. “For a child growing up in Lima, it’s like a Marvel comic,” Zea told me recently. It was not until 2013, when he was twenty-four and had moved to Cuzco for a photojournalism job, that the myth acquired a more quotidian dimension in his life.

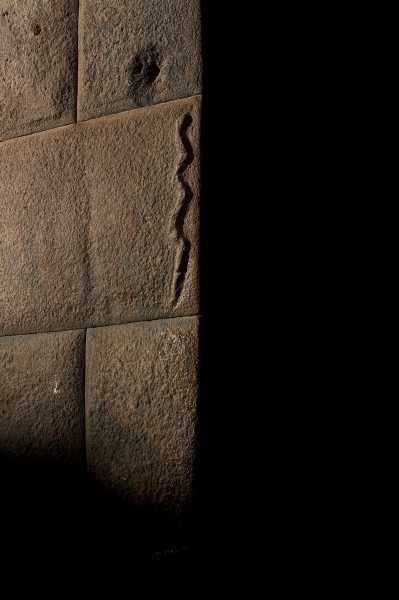

Zea encountered people in the city who still practiced sun worship. He befriended the members of several groups, and even participated in occasional dance rituals. “Cuzco is a city that lives its ancestrality through the sun,” he told me. That practice, though, is inextricable from the region’s colonial history. Catholicism, introduced by the Spanish in the sixteenth century, remains the city’s most widely practiced religion; in a heavy-handed display of Western imposition, at the plaza Santo Domingo, a majestic old church and convent sit atop the ruins of the even older Qorikancha, the Inca temple of the sun. But certain pre-Hispanic beliefs have been incorporated into Catholic festivities. During the first months he lived in Cuzco, Zea was intrigued by that tension, which seemed to him more like a bizarre and somewhat uncomfortable marriage than an openly hostile conflict of faiths.

Zea set out, at one point, to document this syncretism. He took a photograph one day of a man on the street who carries a large golden cross while dressed as the Ukuku, a bearlike creature in Andean mythology. The juxtaposition of the traditions is fairly straightforward, but an altogether different figure—or, rather, the suggestion of one, looming in the background—makes the image somewhat unsettling. A hand, seemingly disembodied, emerges from shadows behind a hefty wooden door, with a crisp white sleeve enveloping its wrist. The spectral presence lends the photo an uncanny ambiguity that would come to characterize Zea’s work in Cuzco. Slowly, he realized that what he wanted to capture was not religious syncretism but the sun itself, how it falls upon the modern city, what it reveals, and what remains obscured.

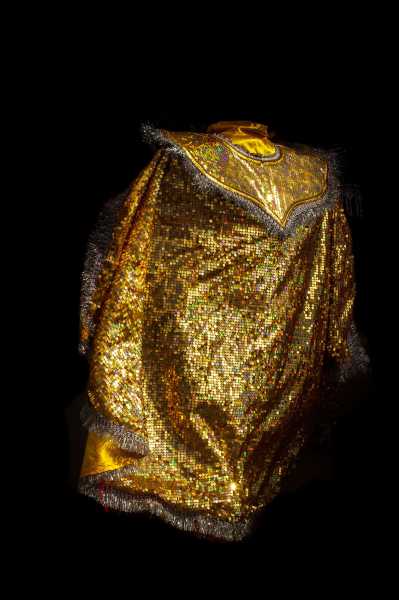

The series that resulted is titled “P’unchaw,” which roughly means daylight in Quechua, a local Indigenous language. P’unchaw was also the name of an ancient Incan idol, allegedly rendered in solid gold and lost after the conquest. “The Incas believed that gold was the sweat of the sun, and so its value for them wasn’t monetary but spiritual,” Zea told me. Again, he thought of colonization, though in different terms. “The Spanish could take the gold,” he said, “but they couldn’t steal the sun.” That idea is implicit in these photographs: a puddle of rainwater gleaming on a cobblestone street; a grid of shadows and sunlight hitting the textured stucco of a building’s façade; the thousand flickers of a sequinned garment caught mid-stride.

On certain days of the year, near the Qorikancha, a bank with a door made up of golden plaques reflects the early-morning sun. Zea spent so many days photographing the surface that, at one point, he began experiencing pareidolia, seeing distinct patterns in a random set of shapes. “I could see a bear to the right, which reminded me of the Ukuku,” he said with a soft laugh, acknowledging that the confession veered toward mysticism but standing by it nonetheless. “Under the spell of my personal journey, it was the sun speaking to me,” he said.

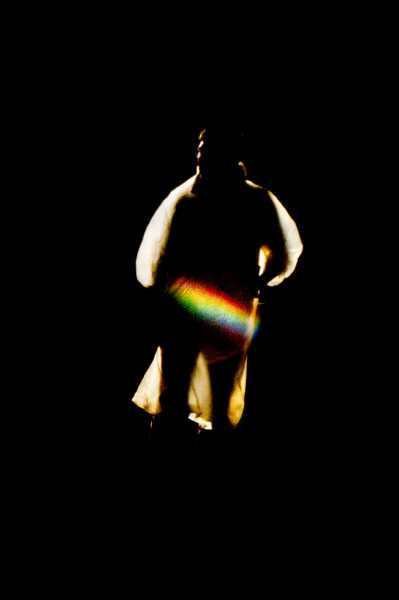

The sun is hardly novel subject matter, but Zea eludes cliché through abstraction. His use of high contrast often erases all context, leaving only fragmented subjects that can make an image resemble a collage more than a photograph. Five adults and a child face a source of light, presumably the sun; they squint, lowering their gazes and shielding their eyes with outstretched arms. It is a strangely beautiful scene. What are they beholding? Zea told me, but I found the image even more striking when I didn’t know.

Sourse: newyorker.com