Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your inbox.

“Constellation,” a Diane Arbus exhibition at the Park Avenue Armory (through Aug. 17), includes more than four hundred and fifty famous, little-known, and unknown photographs from her brief career, cut short by suicide in 1971, at the age of forty-eight. Controversy dogged her posthumous shows and publications, and though it has mostly been replaced by a profound appreciation, Arbus isn’t easy to love. The work remains tough, provocative, and brilliantly dark. The curator Matthieu Humery’s installation turns the Armory into what looks like a construction site—a dense network of metal structures hung with framed pictures at every height and mirrors at strategic spots. The immediate effect is at once overwhelming and thrilling: an amusement-park ride you never want to get off, with an astonishing image at every turn.

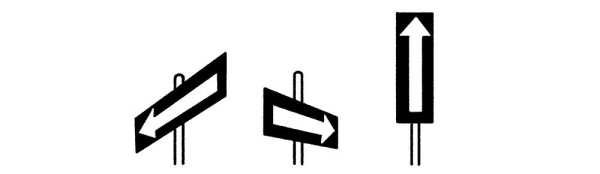

Detail of “Diane Arbus: Constellation,” 2025, Park Avenue Armory.

Art works © The Estate of Diane Arbus / Courtesy Collection Maja Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation; Photograph by Nicholas Knight

All the photographs at the Armory—now in the collection of Maja Hoffmann’s LUMA Foundation, based in Arles, France—are printer’s proofs, made by the photographer Neil Selkirk, the only person authorized to make posthumous prints from Arbus’s negatives. Selkirk retained one image from every edition of Arbus’s work he reproduced—an invaluable cache, considering his long and dedicated involvement with the material. Because “Constellation” includes every one of those pictures, it’s not just the largest Arbus show to land in New York but the most eye-opening and eccentric.

Humery makes the most of that eccentricity, grouping pictures of different sizes and periods and juxtaposing series (of nudists, circus performers, psychiatric-hospital patients) with lesser-seen magazine work and with images from the 1972 Aperture monograph that continues to define Arbus. The result can be unsettling, which is as it should be. The small “Self-portrait, pregnant, N.Y.C. 1945,” of Arbus looking at herself, stripped to underpants, in a full-length mirror, is hung near her picture of James Brown backstage at the Apollo in 1966, flashing a wide, alarming show-biz smile. Celebrities, including Mae West, Norman Mailer, Jayne Mansfield, and Susan Sontag, most shot on assignment, crop up alongside anonymous men, women, and children at Coney Island, in Central Park, on Fifth Avenue, and at summer camp. Arbus gives them all a focussed attention—a look that feels more like curiosity than concern. But Arbus’s curiosity isn’t idle—it’s intense, consuming. That her appetite was voracious is especially evident at the Armory, where she’s everywhere you look and where mirrors mounted on the backs of framed pictures reflect your own prying eyes. (Another huge mirror serves as the show’s rear wall and doubles it, for a fun-house effect.) Selkirk, who studied with Arbus before she died, has said that she was not judgmental. The challenge for us is to see her work in the same way.—Vince Aletti

About Town

Dance

Starting with “Four Quartets,” in 2018, the works that Pam Tanowitz has made for Bard SummerScape have been notable for a level of execution nearly as high as their vaulting ambition. Formally brilliant, the pieces have been in love with beauty and have cautiously flirted with representation. This time, Tanowitz is taking on Beethoven. For “Pastoral,” she has choreographed a dance to the symphony of the same name, or nickname—No. 6—but that music has been replaced with a new response score by Caroline Shaw. Paintings by Sarah Crowner add to the production’s interplay of the abstract and the programmatic, nature and art.—Brian Seibert (Fisher Center at Bard; June 27-29.)

Classical

The Dutch composer Simeon ten Holt saw each of his compositions as “the reflection of a quest for an unknown goal.” In 1976, he embarked on what would become his most well known, “Canto Ostinato.” The piece is sweeping and exploratory, but with a persistent mathematical undercurrent—qualities that should maybe be oxymoronic working in tandem. “Canto Ostinato,” though originally brought to life by multiple pianos, has been performed by a vast range of instruments, including strings, harps, organs, and trumpets. The Grammy-nominated ensemble Sandbox Percussion, in co-production with the American Modern Opera Company, performs the work as part of the Run AMOC* Festival, and Lincoln Center’s “Summer for the City.” The ever-evolving quest continues.—Jane Bua (David Rubenstein Atrium; June 25.)

Art

“Suburb in Havana,” 1958.

Art work © The Willem de Kooning Foundation / ARS / Courtesy Gagosian; Photograph by Owen Conway

Curatorial confusion hangs like a cloud over “Willem de Kooning: Endless Painting,” a big bang of a show that displays the incredible power, imagination, and sheer visual force of de Kooning’s artistry. As arranged by Cecilia Alemani, who is the chief curator at the High Line, twenty-two intellectually robust, soulful paintings are linked, at Gagosian, not by any spiritual or intellectual clues but by repeated motifs found on the surface, or buried just below: eyes, nose, teeth. By limiting what’s shown of de Kooning’s palette—and treating all the creations like marquee works—the installation ends up feeling confusing rather than helpful, but so what? It’s an honor to be amid what amounts to a return to the New York School in New York, where it has been absent for ages.—Hilton Als (Through July 11.)

Movies

The grim spectacle of bullfighting is displayed with an unflinching, intimate glory in Albert Serra’s documentary “Afternoons of Solitude,” which follows the torero Andrés Roca Rey through fourteen corridas in the course of three years. Serra details the ritualized battles, from the wounding of bulls by picadors to the matador’s climactic kill, and observes Roca being dressed in his elaborate costumes by a skilled associate. But the core of the film involves extended scenes of Roca in the ring, taunting and luring and evading the enraged beasts with death-defying maneuvers—turning his back on bulls, wiggling his hips at them—that are as graceful as dance but as dangerous as combat, sometimes leaving Roca bashed and bloodied, yet unyielding. The aesthetic of bullfighting is revealed to be as exquisite as it is terrifying.—Richard Brody (Film at Lincoln Center.)

Soul

Photograph by Sylvain Chaussée

The singer Jasmine Rose Wilson first teased a full-bodied soul sound in 2017, when she released the mixtape “From Dusk ’Til Dawn,” as Baby Rose. Her music is built around her distinct voice, which is husky yet smooth, exuding both subtlety and power. Rose’s début album, “To Myself,” from 2019, set the terms of her sound with measured post-breakup reflections, and in its songs a growing command of her singular instrument gives her music its own gravity. Four years later, the follow-up, “Through and Through,” showed greater mastery over this force, now in service of sumptuous, lounge-ready songs about budding romance. Baring classic R. & B. and funk overtones, its hazy ballads draw you into their embrace and don’t let go.—Sheldon Pearce (Sony Hall; June 27.)

Art

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, more than two million Swedes, Danes, Norwegians, and Finns migrated to the U.S., many of them settling in the upper Midwest. The exhibit “Nordic Echoes” explores the quirky, forest-forward legacy of Scandinavian folk culture on contemporary artists in the U.S.’s northern heartland. On display is a birch-bark guinea-pig carrier, à la BabyBjörn (replete with bite marks); a COVID-era painting depicting masked North Dakotans at a farmers’ market; and a stunningly intricate paper cutting of animals fleeing a forest fire, a nod to recent climate catastrophes. Among the lighter fare, standouts include a polychromatic, aurora-esque abstract drawing, by a Minneapolis-based artist of Sami and Finnish descent; and a pair of ale hens—bird-shaped special-occasion carved drinking gourds. Skål! (Cheers!)—Jennifer Wilson (Scandinavia House; through Aug. 2.)

Pick Three

Jennifer Wilson on three new poetry books.

1. The poetry of Bernadette Mayer (1945-2022) is as whimsical and difficult as raising children, one of her main subjects. In 1978, Mayer published “The Golden Book of Words”—newly reissued by New Directions—a few years after she moved from New York City to Massachusetts, to start a family (with the fellow-poet Lewis Warsh). Mayer’s avant-garde, fragmentary language echoes the cacophony of a full house, or is it the other way around? “Broo ah ha ha / thoughts unravel / run after her.”

2. In life and on the page, the Palestinian poet Nasser Rabah searches through rubble. In “Gaza: the Poem Said Its Piece,” a new translation of his work that includes writings from the onset of the current war and humanitarian crisis in Gaza, he offers, “There you are, giving a silent sermon over a heap / of the dead and move on, just like when you ask the grocer / for something, and move on.”

Illustration by Derek Abella

3. The title of “The Wickedest,” the latest collection from the Nigerian British poet Caleb Femi, comes from a long-running house party in South London’s “shoobs” scene. The party’s history is narrated in verse by an Uber driver picking up a young woman, perhaps taking her home to a working-class council estate—the setting for much of Femi’s poetry, including his début, “Poor.” “The Wickedest” finds poetry in all corners of the club. Someone types lonely verses on his Notes app. The d.j. spits love poetry on the mike: “big up the couple lipsing by the window / you lot been there all night though / you’re blocking the breeze.”

What to Watch

Bill McKibben on the best nature shows.

The new documentary “Ocean” (on Disney+) is vintage David Attenborough, and not many vintages have aged better; he turned ninety-nine last month, which means we should be savoring whatever he produces. But what made this movie so powerful was one scene: the up-close video of the damage done by a trawler as it lawn-mows the sea bottom, over and over. It’s a reminder that at its best—all the way back to Jacques Cousteau—nature filmmaking does its job when it captures not just abundance but absence.

“My Octopus Teacher,” 2020.Photograph from Netflix / Everett Collection

For those who need more underwater content, “My Octopus Teacher,” from 2020, is streaming on Netflix. The story of a South African diver who falls under the spell of an octopus in a kelp forest, it’s the micro-view to Attenborough’s wide angle. Coming onshore at least a little, the 2024 documentary “My Mercury” (for rent on Prime, free on Pluto) chronicles a conservationist who spends eight years on a tiny island off Namibia, chasing away—controversially—an invasion of seals, who endanger the penguins, gannets, and cormorants that have long inhabited its cliffs.

On HBO, you can watch “All That Breathes,” a 2022 documentary account of a pair of Indian brothers who run a bird hospital focussed on rescuing black kites, a common New Delhi species increasingly falling victim to the city’s incredible congestion. The cinematography, the soundtrack (by Roger Goula), and the sound recordings (of, among other things, a band of dump-dwelling rats) are intense; you get an Attenboroughian sense of the sprawling human wilderness that is the Indian capital city.

Another sterling account of an urban bird, this one from the National Film Board of Canada and available, in an abbreviated version, as a Times Op-Doc, “Modern Goose” follows Canada geese through Manitoba (from which thousands of people recently evacuated, to escape vast forest fires). Urban development has made it hard to be a goose; the director Karsten Wall tracks them through strip malls, highway off-ramps, and an awful lot of parking lots. There’s no English accent to guide you—no narration at all, except the soft honking of the geese, somehow carrying on amid it all.

P.S. Good stuff on the internet:

- Cole Escola’s favorite song

- The cocktail of the summer

- Keira Knightley and Rosamund Pike together again

Sourse: newyorker.com