Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

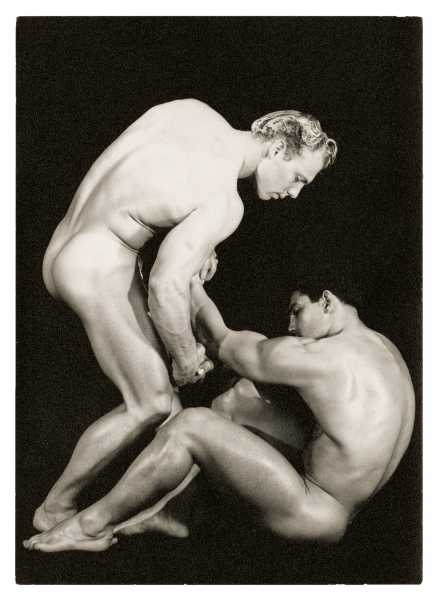

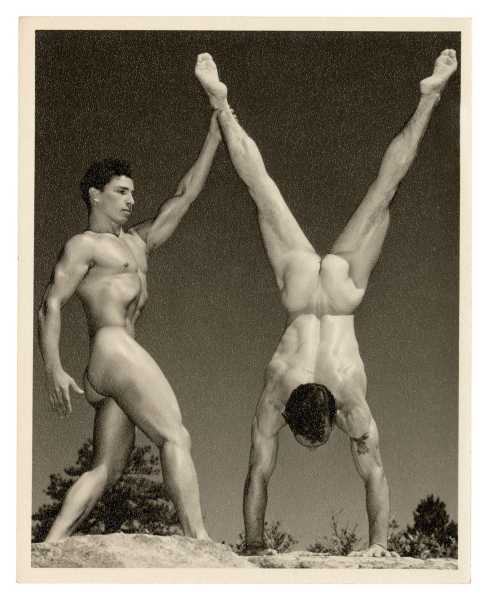

I remember the first time I saw a physique photograph, and I remember being both excited and upset at the sight of it. I was probably eight or nine, a child of the postwar boom, and on vacation with my family at the Jersey shore. We had stopped at a convenience store on the way home from a day at the beach, and I was pawing through the store’s magazine rack while my mother shopped. I don’t remember picking up the magazine, but it opened to a page which stopped and startled me. Two mostly naked teen-agers were posed for a picture titled “Victor and Vanquished,” one slung over the other’s shoulders—the spoils of a heated but not unfriendly war. Both boys were smiling, exhilarated, but I was fixated on their points of contact, especially where the naked groin of the Vanquished touched the Victor’s bare shoulder. What did that feel like? What could that feel like? Thinking about it made me dizzy and more aroused than I realized. When one of my sisters showed up to say we were leaving, I had to cover the tent in my bathing suit, already deflating from embarrassment.

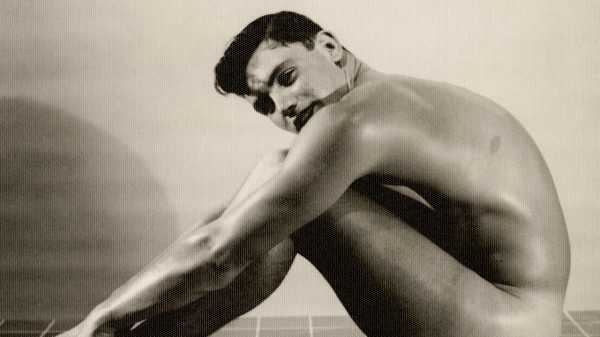

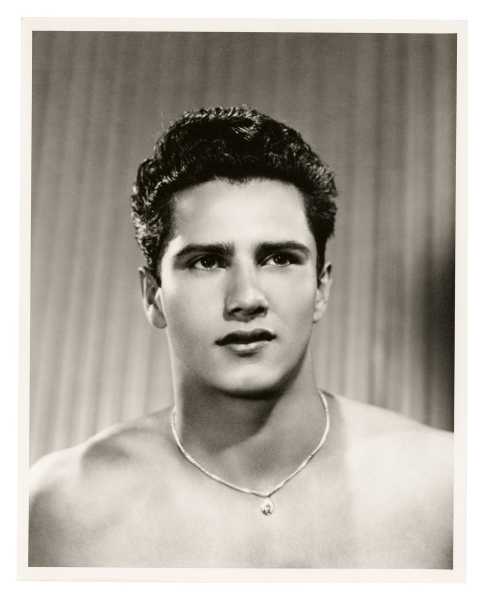

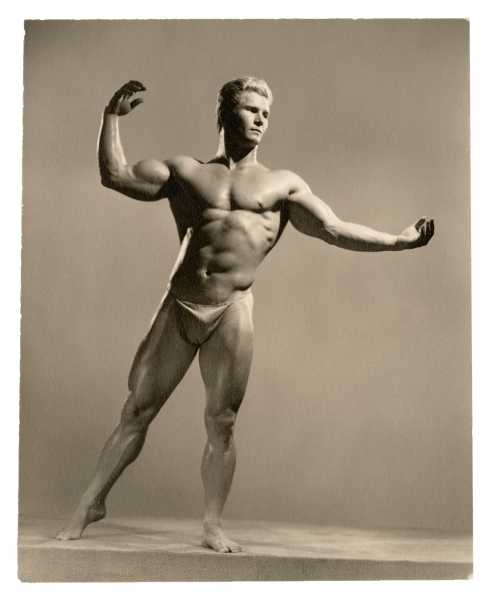

Photograph by Bruce Bellas (Bruce of Los Angeles), ca. 1948

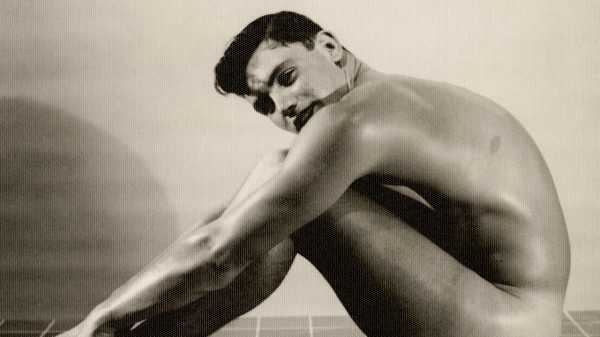

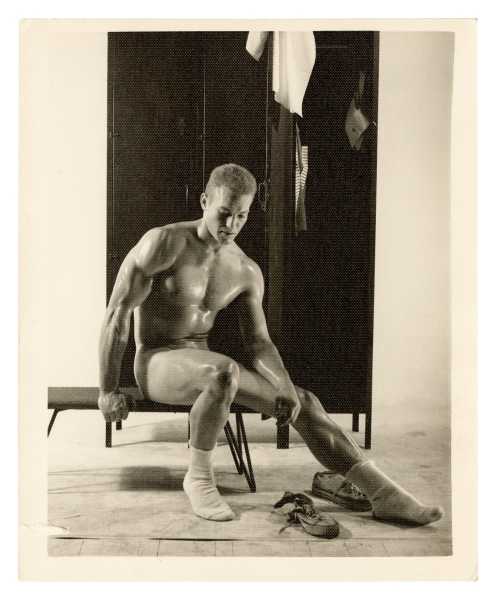

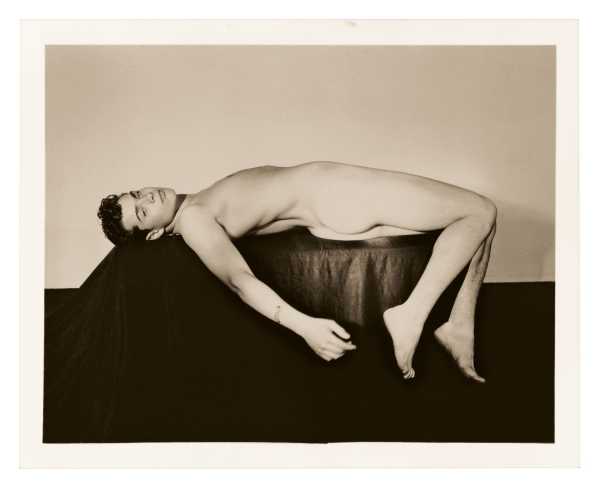

Photograph by Russ Warner, ca. 1945

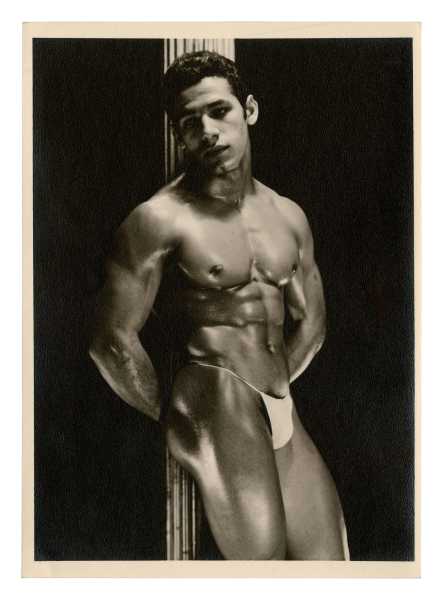

Some years later, I began sneaking home pocket-size magazines like Adonis, Body Beautiful, and Tomorrow’s Man from an out-of-town newsstand. I was still much younger than the publications’ target audience: gay men for whom sex in the mid-nineteen-fifties was furtive, dangerous, and illegal. The photographs, and the magazines that delivered them, were part of an erotic fantasy life that the horny preteen I’d become could only imagine. But that was very much the point; like the women who filled the girlie magazines, these guys were there to excite us. Obscenity laws, most aggressively enforced by the U.S. Postal Service, attempted to keep that excitement within bounds—no uncovered or obviously aroused penises, no affectionate or suggestive physical contact. Pushing those boundaries gave the best physique work a subversive edge. Although these were hardly outlaw enterprises, the liveliest of them had a rock-and-roll sensibility: rules were made to be broken. Models wore thong-like modified jockstraps to cover their genitals, leaving little to the imagination, but that little was enough to rivet us readers; any evidence of bulge was the focus of fevered attention. The models were named, along with the studios, most of which advertised photographs for sale on the back pages. It wasn’t until much later that I paid any of them much attention; I was too caught up in the wet-dream world of physique—a delirium that lasted well into an aimless, protracted adolescence.

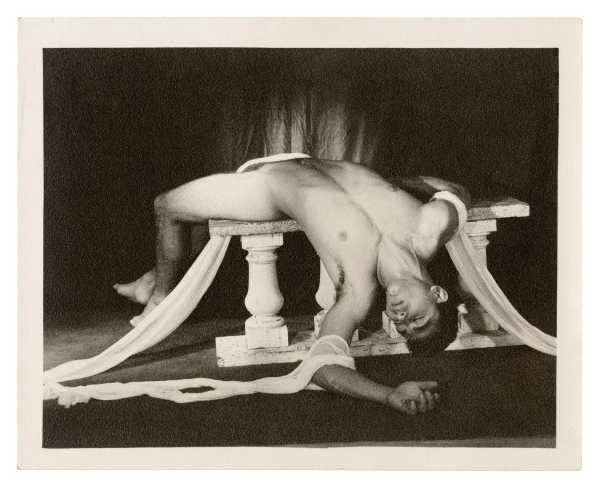

Photograph by Chuck Renslow (Kris), ca. 1960

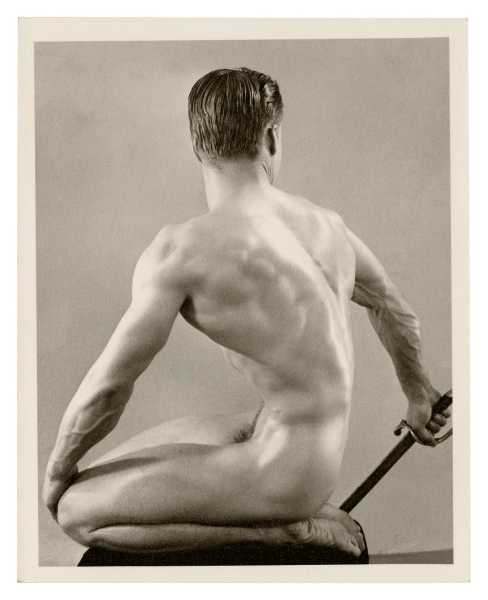

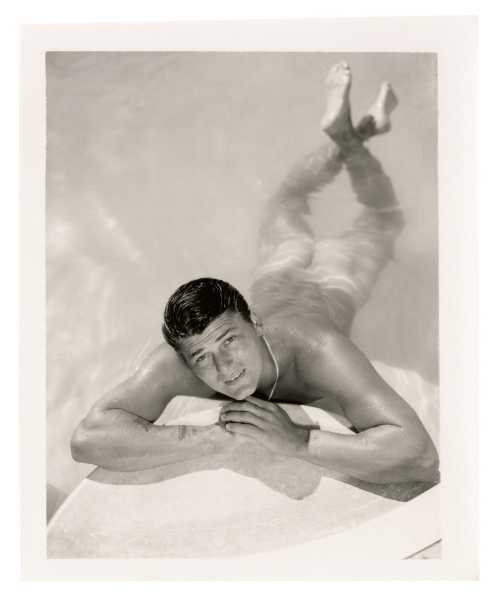

Photograph by Lon Hanagan (Lon of New York), ca. 1960

By the time I saw physique magazines and photographs again, in the early nineteen-seventies, and began collecting them, they were antiques—amusing, campy relics of a time before gay liberation, go-go boys, clones, unabashed cruising, baths as social scenes, and disco. Physique images didn’t just recall charged, formative moments for me, though; the images, at once innocent and repressed, still retained a weird power. They reminded me of my boyhood “American Bandstand” crushes—Frankie Avalon, Fabian, and the Everly Brothers—who all had the same lacquered pompadours as the guys in the posing straps. By then, the idols of my youth looked as classical as Greek statuary compared to the guys slouching balls-out across the color spreads of magazines like Blueboy and Numbers, which were all over newsstands in the nineteen-seventies and eighties, but were soon to become relics themselves with the arrival of AIDS. Yet looking at physique images again, after so much time had passed, I saw their artfulness, their playfulness, and their sincerity. Sure, there were some pretentious amateurs on the other side of the camera, but the most successful physique photographers were pros with recognizable styles. Many of them had started out in long-established muscle-builder magazines such as Strength & Health and Your Physique—for years, the only regular sources of photographs of mostly naked men posing for the camera.

Photograph by Don Whitman (WPG), ca. 1955

Photograph by Constantine Hassalevris (Spartan), ca. 1948

Physique magazines didn’t need to announce themselves as gay, even if they had been able to. Their readers recognized what we now think of as a “gay gaze”: appreciative, even avid, but not uncritical; at once warm, cool, and knowing. As a result, many of the best physique photographs are portraits, but even when we’re not looking into their faces, the men are tantalizingly alive. Readers understood the necessity of balancing discretion and seduction, subtlety and audacity. Early physique photographers took classical statuary as their inspiration and Hollywood glamour portraits as their models for lighting and setting. Some of the men who posed were professional bodybuilders, including stars of the international circuit, but most were handsome athletes, aspiring actors, well-built ex-marines, or models looking to augment their portfolios: men who had reason to keep their bodies in great shape. Because a number of the most successful photo studios were based in Los Angeles, photographers could choose from a large and constantly replenishing population of young men anxious to be recognized, to be chosen.

Photograph by Cavalier, ca. 1955

Photograph by Cavalier, ca. 1955

The photographs here are a small part of a collection I cannot begin to quantify, representing a wide range of the physique studios active in the United States from the late nineteen-thirties until the early seventies. These studios were rarely larger than a one-car garage, but the photographers’ results were as unique as their signatures. For work that was essentially commercial, the images are often unexpectedly touching, especially in scenes of men holding hands, deliberately blurring the line between friends and lovers. Physique photographers may not have considered themselves outsider artists, but for years these photographs remained private—shared among a population of men who were just beginning, against all odds, to frame a public identity. Now, long after the original images have been appropriated as club flyers and campy greeting cards, I can’t help seeing them as souvenirs and mementos. The past they represent is a queer utopia, a safe space for erotic fantasy. No wonder they drove the postal authorities crazy.

Photograph by Richard Fontaine (Apollo), ca 1945

Photograph by Don Whitman (Western Photography Guild), ca 1960

This is drawn from “Physique,” which is published by Mack Books.

Sourse: newyorker.com