Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Hilton Als

Staff writer

You’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your in-box.

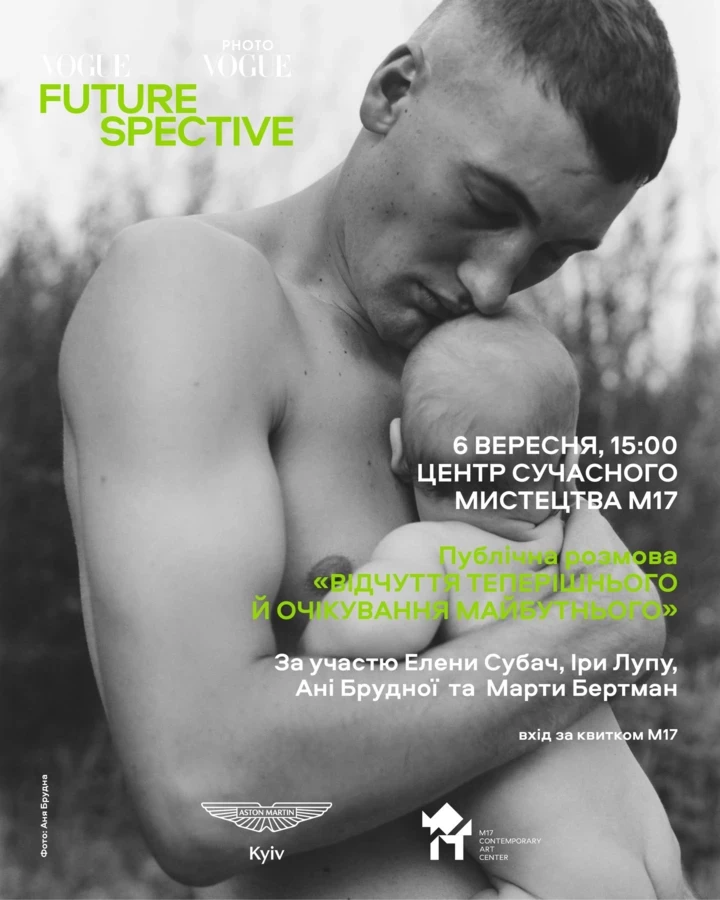

In 1971, the painter, quilter, and children’s-book author Faith Ringgold went to prison. She was not incarcerated; she went as an artist and an activist, to create a work for the Women’s House of Detention (as it was then called) on Rikers Island. Commissioned with a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts to devise a piece for a public institution in New York, Ringgold chose a women’s prison. Eventually, she made a painting. Titled “For the Women’s House,” the brightly colored work is divided into eight sections, and depicts women in professional roles that were then largely unavailable to them—politician, sports figure, construction worker. Hope was in the making, Ringgold’s work seemed to say. If you could dream it, you could be it.

Faith Ringgold unveils “For the Women’s House,” in January, 1972.

Photograph by Jan Van Raay / Courtesy Aubin Pictures

But then, after more than twenty years at Rikers, the painting disappeared. In 1988, the Women’s House of Detention was relocated to a new building. Ringgold’s painting was not. It was Barbara Drummond, a correctional officer and a former volunteer at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, who eventually tracked down “For the Women’s House,” in a staff kitchen in the old building. It had been painted over. Once it was found, Drummond launched a campaign to get the work restored—and it was, but then it was improperly hung. This “lost” work acts as a metaphor for the incarcerated women you see in the empathetic film “Paint Me a Road Out of Here,” deftly handled by the filmmaker and activist Catherine Gund, and now at Film Forum.

Faith Ringgold and Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter.

Photograph courtesy Aubin Pictures

The expertly edited documentary tells us that, among other things, the majority of people held in local jails have yet to be convicted of a crime, but can’t afford bail. They’re just sitting there, waiting; aspiration isn’t part of the deal. And whereas Ringgold stands at the crux of two institutions, the prison structure and the museum structure—the restored painting has since been displayed at the Brooklyn Museum—Gund introduces us to a young multimedia artist named Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter, who tells her story, and many others besides. Baxter, imprisoned in Philadelphia while pregnant, was tied to a hospital bed while giving birth; she saw her son once before he was taken away. Seven months later, she was released from prison. Part of what Baxter wants to show, in her work and through the film, is how two very different artists from different circumstances tried to instill something like hope in a situation that’s meant to shut hope out. When you go inside, Baxter says, “You’re rubber-stamped with all of these negative connotations about who you are or what you represent.” And, of course, those negative connotations act as a kind of branding on the soul. For both Ringgold and Baxter, the point of making work for and with women who have been jailed is to say, by example, that if you can speak—itself an act of defiance—you can say your name.

On and Off the Avenue

Rachel Syme seeks out vintage finds from the heyday of the first New Yorker issues.

In November, 1925, the twenty-three-year-old writer Lois Long inaugurated On and Off the Avenue, the magazine’s fashion column. That summer, the New Yorker editor Harold Ross had scooped her up to write the magazine’s night-life column (soon to be called Tables for Two), chatty dispatches from the flapper underground which she signed “Lipstick”; she was known to go out dancing at speakeasies all night and file gossipy reports at dawn. By the fall, Ross added fashion columnist to Long’s duties, and she signed her On and Off pieces with her own initials, L.L. (Writing about shopping was, perhaps, less risky than writing about bootleg beverages.) Even in her early twenties, Long held staunch opinions on stocking colors and children’s frocks, Christmas cards and muskrat coats. In one early piece, she complained about American women’s deference to French fashions. (“Go ahead and buy an original little Chanel around here if you want to,” she wrote in 1927. “And watch it drop to pieces on your back the second wearing.”)

Illustration by Debora Szpilman

In light of the magazine’s hundredth anniversary, I have been thinking a great deal about Long and the clothing she wrote about in those early days. She covered marcasite hatpins and surah-silk Boivin scarves, “milky powder blue” dresses in crêpe de Chine, long necklaces of Técla pearls. I wondered, how can one shop like Long now, without a feeling of hammy “Great Gatsby” cosplay? Poking around recently, I found that there is much to buy from around The New Yorker’s early years which still feels fresh, a century later. At 9th St. Vintage, in the East Village, the owner, Meri Civorelli, offers dainty, cream-colored, light-cotton Edwardian blouses, many of them embellished with cheerful scalloped edges or lace collars (priced around $200). Civorelli suggests wearing one with a pair of high-waisted jeans and a leather jacket to give them a modern edge. “I can barely keep them in stock,” she told me, “because they are the perfect white shirt.” For more daring shoppers, Civorelli sources quirkier items, such as a nineteen-twenties Levi Strauss hunting jacket ($450) and several century-old silk slips that can range from $225 to $1,200. In Chelsea, the vintage jewelry boutique Pippin offers pieces featuring marcasite, or white iron pyrite, a silvery crystal that forms in a distinctive “cockscomb” pattern and was all the rage among the bathtub-gin set. According to the store manager Daniela Oropeza, the gem is quite affordable—a marcasite-and-carnelian bracelet recently sold for $185—and is a great entry point into the world of antique baubles. If you want to veer into the vintage-homewares department, I recommend visiting the studio of the Brooklyn Teacup, in Park Slope, where Ariel Davis makes lovely tiered trays out of repurposed antique china. Davis has made many creations using nineteen-twenties materials, including Japanese lustreware, Bernardaud plates, and rare Noritake cups and saucers.

If you are willing to travel—and enjoy less picked-over thrifting—there are many treasures within driving distance. Paper Doll Vintage Boutique, in Sayville, N.Y., is a wonderland of intricate beaded bags with wristlet straps (these were known to flappers as “dancing bags,” as they would stay on the arm during energetic Charleston sessions) and elegant Whiting & Davis clutches made out of tiny mesh scales. The owner, Dominique Maciejka, who opened the store in 2012, is currently rebuilding her inventory of opera coats and hand-bobbined blouses after her first location burned down, this past October, but she will open a new store in the spring, and for now is selling via Instagram. Malena’s Vintage Boutique, in West Chester, Pa., has one of the best twenties collections in the region. The owner, Malena Martinez, studied fashion design at Pratt before moving to her home state to start her archival empire; she also has a storeroom full of period clothing that you can see by appointment (or shop on eBay and Etsy). Her pieces range from the humble (lavender silk-satin tap pants for $65) to the truly resplendent (a gold lamé and fox-fur cocoon jacket, by Mary Sachs, for $1,900). Martinez often sells clothing to movie sets and major retailers for use as inspiration, and she had much to say, in the quippy Lois Long tradition, about bringing twenties items up to date. “Take a silk duster coat and pop it over a band tee and patchwork jeans, and skip the finger waves so you don’t look like you stepped right out of Ladies’ Home Journal,” she said. “But, also, you can wear a piano shawl any day of the week. It’s all about the attitude.”

A New Yorker Quiz

Test your knowledge of our one-hundred-years-young magazine. Can you guess the answer without peeking?

-

Who gave Eustace Tilley his name? Hint: He who christened “the monocled toff who became the publication’s mascot” also gave him “an even dandier grandfather, Terwilliger Tilley,” Jill Lepore writes, in a history of The New Yorker’s editorial battles. He is also the author of the series, in 1925, called “The Making of a Magazine.” Click to see his byline on an early installation of the series.

-

Which celebrated novelist was the subject of a 1950 Profile by Lillian Ross? Hint: “It would seem the kind of piece that occasioned Janet Malcolm’s dictum that all journalism is immoral, with the reporter out to get the subject and the subject realizing only too late that he is being got,” Adam Gopnik writes in his exploration of that very complicated relationship. Click to read the infamous Profile.

-

In the year 2000, Joan Didion wrote a defense of which ambitious homemaker? Hint: Jia Tolentino writes, in a reflection on the story, that “the pairing—more accurately, a doubling—is unrepeatable: one mononymous perfectionist analyzing another, one carapace reflecting another’s gleam.” Click to discover Didion’s double.

Sourse: newyorker.com