Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In the winter of 1999, an odd little movie named “Office Space” gleefully demolished the conventional portrayal of white-collar work. The film, directed by Mike Judge, was set in a fictional software company called Initech; many scenes played out under fluorescent lights in a featureless warren of cubicles. “Mike was always very clear that he wanted it to look realistic,” Tim Suhrstedt, the film’s cinematographer, recalled in a 2019 interview. “He wanted the place to be sort of ‘gray on gray’ and feel almost surreally boring.” Ron Livingston, the movie’s lead actor, remembers Judge walking through the set right before filming, pulling down any detail—plants, photos—that added splashes of color or personality. “Office Space” suffocates its characters in drabness; it’s office as purgatory. The film was part of a broader aesthetic movement that portrayed modern workspaces with an antagonistic suspicion. It came out a month before “The Matrix” and a year and a half before the British version of “The Office.”

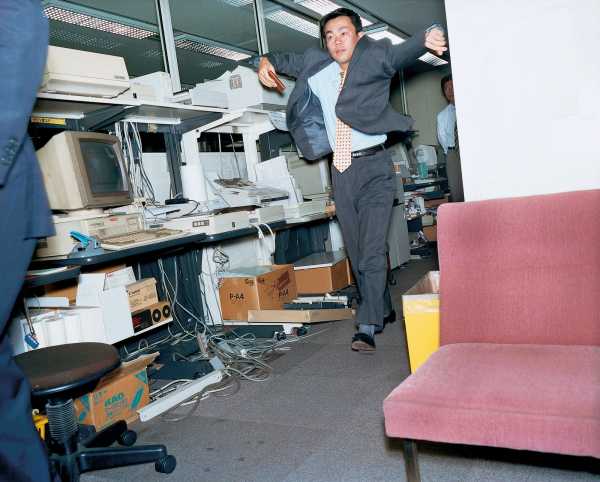

Around the same time that Judge was making his movie, the Swedish photographer Lars Tunbjörk was documenting remarkably dreary corporate spaces in New York, Tokyo, and Stockholm. His iconic collection “Office,” first published in 2001 and elegantly reissued by Loose Joints this month, shares many elements of the “Office Space” style. The lighting is stark and the color palette is dominated by grays and off-whites. In some photos, Tunbjörk creates a sense of claustrophobia, as when a low-angle shot captures a man bounding down an office corridor. The ceiling seems to loom mere inches above his head. In another photo, Tunbjörk portrays stark isolation: a woman stands alone on an empty floor, the lines of filing cabinets and overhead lights converging to a distant vanishing point. The emergence of this aesthetic at the turn of the millennium was not arbitrary. At the time, our relationship to office work began changing rapidly, and it hasn’t stopped since. “Office” may look like a quintessential artifact of its period, but it also manages to feel contemporary, because it captures a mood that still infuses our professional lives.

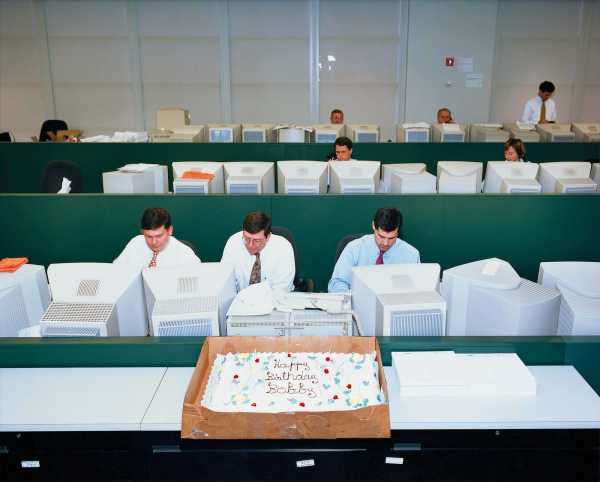

“Stockbroker, New York 1997.”

Tunbjörk was born in the city of Borås, in southern Sweden, in 1956, and began taking photos for his local newspaper at the age of fifteen. He began his fine-arts career shooting in black-and-white, in the style of the Swedish master Christer Strömholm, but later switched to color, drawing inspiration from vivid, large-format scenes of everyday life by American photographers such as Stephen Shore and William Eggleston. Tunbjörk first gained international recognition for his 1993 book “Country Beside Itself,” which captured the quirks of Swedish culture. By the time he published “Office,” he had expanded his range to document the absurdity and ironies of modernity worldwide.

“Car manufacturer, Gothenburg 1997.”

“Firm of accountants, New York 1997.”

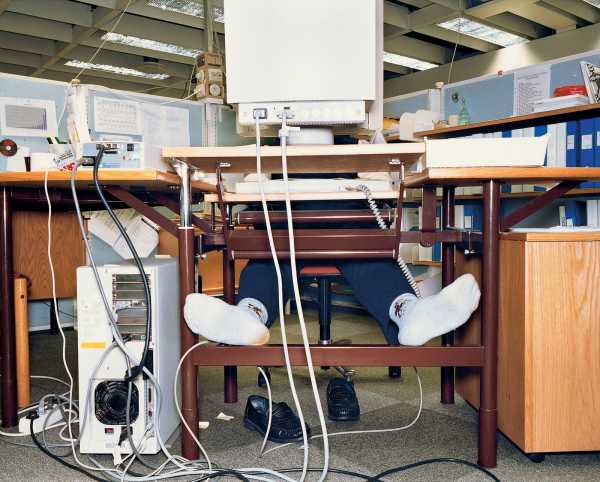

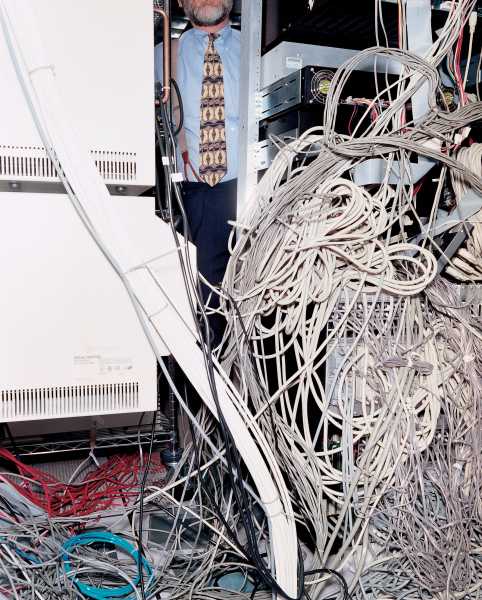

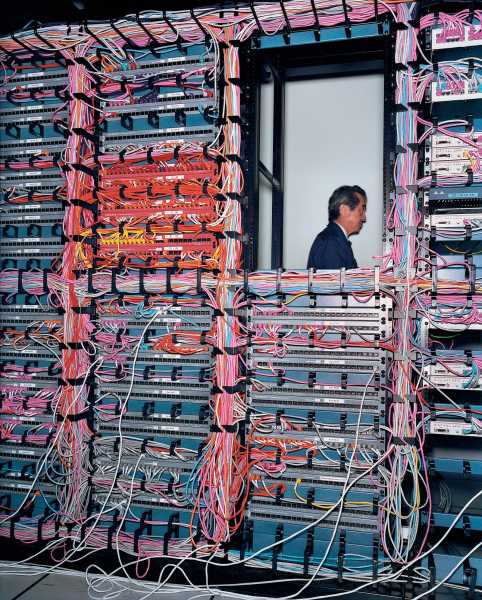

Judge and Tunbjörk were depicting the same kinds of spaces, but Tunbjörk’s work proved the more perceptive. Part of what separates them are their respective theories for why the office had become hostile. In “Office Space,” Judge suggests that the problem is managerial; in a pivotal scene, Ron Livingston’s character complains that he has eight different bosses. This was hardly a new complaint, however: people had been making fun of middle managers for decades. Tunbjörk’s photos in “Office,” by contrast, point to a more contemporary culprit: technology. One photo features a woman kneeling in front of a metal drawer, a computer monitor looming to her left; with her face obstructed from view, she looks like an anonymous supplicant. Another shows a pair of feet below a desk that is piled with gadgets and wires. A particularly memorable shot depicts an older man through a small, window-like opening in a wall of server racks and network cables.

In the nineteen-seventies and eighties, many workers, especially in the manufacturing sector, lost their jobs to high-tech tools. But Tunbjörk’s photos are less about technology replacing workers than about technology oppressing them. In the nineties, an I.T. revolution placed networked computers on the desks of countless knowledge workers. With these networks came e-mail, and with e-mail came a new approach to work centered on ongoing, ad-hoc, back-and-forth interactions that unfolded through sterile digital text. Work as a place where humans gathered to collaborate in physical spaces—to have insights and solve problems together—gave way to a new order in which humans became glorified network routers, shifting and sorting a ceaseless stream of bits. Office jobs became more frantic and fatiguing. The anonymous man between the server racks in Tunbjörk’s photo seems imprisoned by the apparatus of networking. He was an archetype for an emerging digital worker.

“Stockbroker, New York 1997.”

“Stockbroker, Tokyo 1999.”

“Lawyer’s office, New York 1997.”

“Customer care center, Sioux Falls 1998.”

It’s a little sad to open a book like “Office” today. Tunbjörk died in 2015, but the themes in his work only intensified as laptops, smartphones, and remote work helped to speed up and dehumanize our jobs. Tunbjörk was attempting to portray a new and uncomfortable reality about office life in the early two-thousands—one that demanded a reaction. Today, the alienation of hyper-connected office work feels neither novel nor strange. We’ve internalized a depressing reality in which new e-mails constantly refill our in-boxes and haunt every waking moment; we forget even to be upset about it. But perhaps Tunbjörk’s classic photo collection can help remind us that work doesn’t have to be this way. By emphasizing the strangeness of work in the Network Age, “Office” might help us rediscover a sense of urgency and possibility: our jobs don’t have to be frenetic and always on. We don’t have to bow before computers or squeeze ourselves into the spaces between the wires, like Tunbjörk’s subjects—or, for that matter, to quietly suffocate in our cubicles, like Judge’s characters. We still have the ability to demand something better.

“Stockbroker, Stockholm 1998.”

“Lawyer’s office, New York 1997.”

“Bank, Tokyo 1999.”

“Advertising agency, New York 1997.”

Sourse: newyorker.com