Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Stefan Ruiz was twenty-four years old and a recent graduate of U.C. Santa Cruz when he travelled to Côte d’Ivoire to help an art-history professor with a project. They went to Bondoukou, near the Ghanaian border, where they researched Islam’s influence on traditional African art. Ruiz took pictures of mask makers, weavers, and festivals. When he returned home to Northern California after nearly two years away, he got a job at a restaurant in San Francisco, where a co-worker asked to see his photos from West Africa. The co-worker liked them, and asked whether Ruiz would put together a slide show for his girlfriend and her mom. Ruiz recalled approaching the doorstep of one of San Francisco’s iconic Painted Lady houses, carrying four slide carrousels, a projector, a cassette player, and a mixtape with music to accompany his presentation, and thinking, Oh, shit, who lives here? It was Alice Walker’s house; her daughter, the writer Rebecca Walker, was the co-worker’s girlfriend. Alice Walker liked Ruiz’s work and helped him get a show at a local cultural center. She also gave him a twenty-five-hundred-dollar grant.

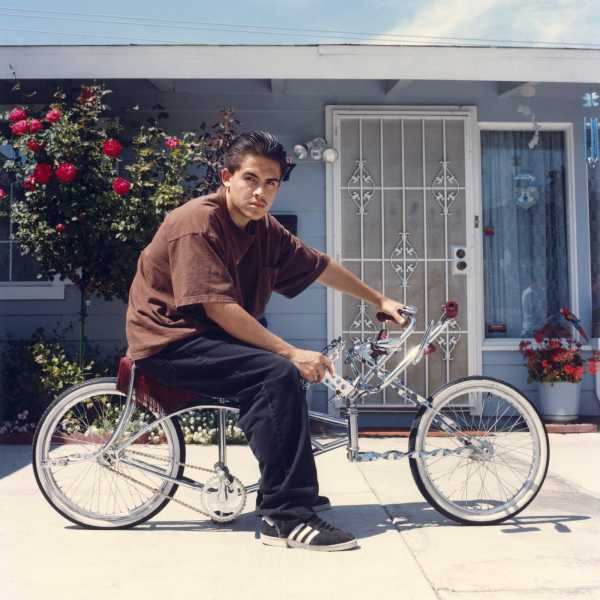

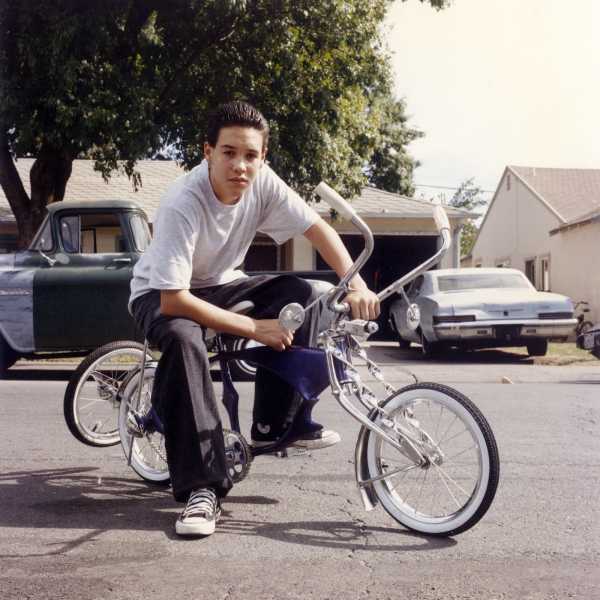

Ruiz spent the money Walker gave him on a used Hasselblad, a medium-format camera that used square negatives six centimetres by six centimetres in size. Astronauts brought a Hasselblad with them to the moon. Ruiz brought his Hasselblad and a couple of other cameras to photograph kids with their lowrider bikes. Lowriders are usually customized cars with shiny rims, plush interiors, and candy-colored paint jobs. They are often emblazoned with the names of loved ones and images of calaveras, Aztec rulers, heroes of the Mexican Revolution, the Virgin of Guadalupe, “Smile Now, Cry Later” masks, and other symbols of Mexican American culture. The kids Ruiz photographed hung around garages and body shops in Sacramento, San Jose, Watsonville, and Cupertino. They idolized “the guys with the cars,” Ruiz told me, but they were too young to drive, so they bided their time tricking out bikes.

Ruiz’s subjects stare at the camera as they stand or squat behind, or sometimes sit on, their bikes. In some of the shots, lowrider boys stand beside lowrider men and their cars, or with moms, sisters, girlfriends, and friends whose style, pose, and gaze complement theirs. Their bikes and their clothes are often red, the color of the San Francisco 49ers football team, as well as the norteño gangs in the Bay Area, with which some of Ruiz’s subjects were affiliated. In some of Ruiz’s photos, the lowriders flash a one and a four with their hands: “N” (for “norteño”) is the fourteenth letter of the alphabet. The working-class culture of the body shops where they toiled over their bikes, in addition to the gang aesthetics that suffused many Mexican American communities in the early nineties, influenced their fashion choices of oversized shirts, baggy pants, and sneakers.

Ruiz photographed the lowriders in the early nineties, when California Governor Pete Wilson championed tough-on-crime and anti-immigrant measures, such as a “Three Strikes” law, which condemned repeat offenders to sentences of twenty-five years to life in prison, and Proposition 187, a ballot initiative that would have denied undocumented immigrants access to public services such as non-emergency medical care and education. Ruiz was teaching an art class at the San Quentin prison, and he saw the incarcerated people he worked with, including Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans, as more than the villains that many Californians understood them to be. Ruiz wanted to show subjects as they wished to be seen, and this impulse shaped his approach both to the lowriders and to subsequent projects. He travelled to Monterrey, Mexico, where he took pictures of Mexican youth obsessed with Colombian fashion and music, especially cumbia and vallenato. They became known as Cholombianos, because of their unique style, defined by a mix of Mexican American cholo culture and Colombian references. Ruiz told me that they called themselves Kolombias or Vallenatos, after the folk music they listened to. He also produced a book of photographs of Mexican telenovela stars staring lustily at the camera.

Ruiz later photographed celebrities and political figures such as Bill Clinton, Henry Kissinger, and the former Bolivian President Evo Morales. On a hot summer day in 2004, he photographed Donald Trump at Trump Tower. The first season of “The Apprentice” had aired earlier that year. During the shoot, Ruiz said, Trump pointed at him and repeated, “You’re fired. You’re fired. You’re fired.” Ruiz asked him to stop because he had seen enough of those shots and doesn’t like it when subjects point their fingers at his camera. Trump seemed “kind of taken aback,” Ruiz told me. He was on assignment for the Sunday Telegraph Magazine, and when they wrapped up Trump asked him to stay and take more pictures of him that he could blow up to life size and place in the lobby. Trump “ended up buying the photos,” Ruiz said. “He did pay, but it wasn’t much.”

Sourse: newyorker.com