Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

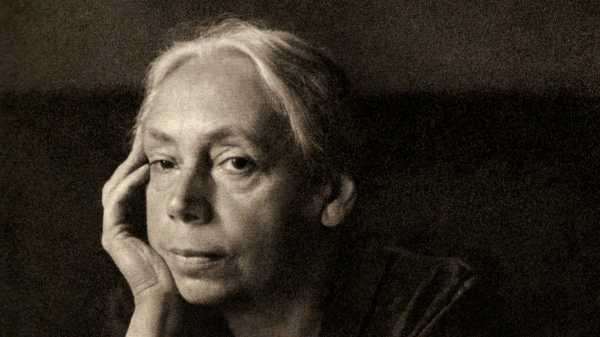

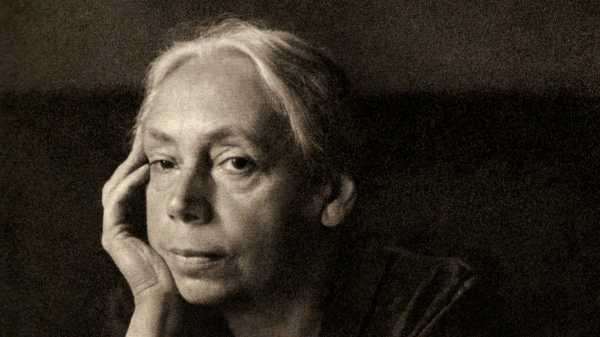

On my only trip to Berlin, in 2019, I saw a lot of Käthe Kollwitz. I walked through Kollwitzstrasse and Kollwitzplatz, near the site of her home, in Prenzlauer Berg. At the Staatliche Museen and at the museum that bears her name, I studied her etchings, with their threadlike details of landscapes of combat, and her political posters, with their spare female figures. A reproduction of her Pietà sculpture, “Mother with Her Dead Son”—her titles are never oblique—sits in the Neue Wache memorial, in the center of the city, as a remembrance of the victims of war. What looks, at first, to be a triangular black mound reveals a cloaked woman, curved around a young corpse, her fingertips touching his. Many of Kollwitz’s German contemporaries, in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, took war and revolution as their subjects. But her work still scrapes us raw.

The Museum of Modern Art has convened a major Kollwitz retrospective, the largest such show in the U.S. in three decades and the first in New York City. The exhibition brings together more than a hundred pieces, focussing on her lithographs, etchings, woodcuts—her primary media—but rewinding them into sketches and drafts that reveal how they came to be. Though printmaking is an extension of drawing, its reliance on metal tools and near-infinite reproducibility can create a distance between artist and viewer. The exhibition seeks to close this gap. (The curators did their best to dim the lights and shield her work from the din of the rest of the museum.) I felt close to Kollwitz as I stood before the tentatively drawn hands in the marginalia of an unfinished self-portrait; I noted the change in a subject’s posture, from resigned, in a pencil-and-ink sketch, to rageful, in a finished etching.

Kollwitz was born in East Prussia, in present-day Russia, in 1867, lived most of her life in Berlin, and died outside Dresden a few months before the end of the Second World War. She devoted herself to art at a time when it was closed off to most women as a career. She married a doctor, Karl, who treated garment workers in a peripheral area of Berlin, and Kollwitz passed through the waiting room of his practice to get to her studio. The patients were often chronically ill as a result of working long hours in sweatshops. Women, young and old, lacked access to contraception, enduring one pregnancy after another. (Kollwitz donated work to benefit the League for the Protection of Mothers and Sexual Reform, which advocated for the right to abortion.) “Only when I became acquainted with the women, who came to my husband seeking aid and incidentally also came to me,” she wrote, “did I truly grasp in all its power, the fate of the proletariat.”

The artistic currents of her time—Impressionism, Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism, Neue Sachlichkeit, Dada—privileged masculine subjectivity. Kollwitz’s art was not only figurative but accessible, and put women, especially mothers, at the center of the action. The animating tragedy of her childhood had been the death of her infant brother, Benjamin, and its effect on her mother. (Two other siblings had died as infants before Kollwitz was born.) Kollwitz feared that her mother would lose her mind. She wrote, “It must have been her years of suffering which gave her forever-after the remote air of a Madonna.” Later, as a mother herself, Kollwitz almost lost her first son, Hans, to diphtheria; her second son, Peter, whom she’d allowed, as a teen-ager, to enlist in the German Army at the start of the First World War, was killed in battle.

Kollwitz made intimate pictures based on real, historical events. In the masterly print cycles “A Weavers’ Revolt” and “Peasants’ War”—think of the velvety, layered engravings of Dürer, but secular—the violent confrontations of class incorporate womanly indignities: rape, the death of a child, the way hunger can shatter a home. In “Sharpening the Scythe,” the third of seven prints in “Peasants’ War,” a woman holds a blade in front of her face. Her knuckles are enormous, gnarled like the roots of a tree. She’s strongly lit, as if caught in a camera’s flash, and squints beyond the frame.

One of my favorite parts of the MOMA show is the wall dedicated to variations of the etching “Woman with Dead Child,” from 1903, when Kollwitz was in her mid-thirties. It’s an abstract, two-dimensional take on her (and Michelangelo’s) Pietà. A mother, or the shape of one, sits cross-legged, folded over a limp figure perpendicular to her lap. Both the woman and child are unclothed, their faces indistinct. The woman’s right hand and the toes of her right foot express clenching strain. According to the catalogue, Kollwitz used herself and her younger son, then seven years old, reflected in a mirror, as the models.

I had seen the final iteration of this piece before, as a black intaglio print. This time, I saw it multiplied, each version conveying a different day or shade of mourning. In one, the etching is faint, a ghostly gray mark on textured off-white paper—living and dead disappear together. In another, the background and parts of the mother’s body are worked over in a blue wash—a painterly feel. One version isn’t a print at all but a drawing in chalk and graphite, with finger smudges at the paper’s edge that look eerily fresh. The repetition, of drafts or experiments, shows how much creativity a mechanical process can afford.

Kollwitz drew and sculpted herself throughout her life. There are many self-portraits, using various materials, that track the progress of her oval face, the hair pulled back into a bun, those large, hooded eyes. She does not efface the inevitable wrinkles and saggy bulges, or the private emotion—joy, sexual desire, despair.

In her fifties, she heeded Lenin’s call to publicize the famine in Russia (“Help Russia,” one of her posters reads), travelled to Moscow, befriended members of the Communist Party of India, and showed art in a pacifist exhibition alongside Otto Dix. She welcomed her first grandchild; Hans and his wife, another printmaker, named him Peter. Kollwitz made a dramatic woodcut cycle called “War,” exploring different victims, or poses, of conflict. “The Mothers,” the best known work from this series, is a claustrophobic blob of black in cleanly chiselled negative space. A crowd of women, eyes bulging, form a protective circle around an unknown number of children, indicated by two little faces that have managed to peek out. There is squeezing and grasping; striations indicate the effort in arms and hands. In “The People,” a woman wearing something like a black isdal fills most of the frame.

Kollwitz’s final print cycle, “Death,” from the nineteen-thirties, is among her most gestural work. She started it shortly after the Nazis’ parliamentary victory in 1932; she and her husband had campaigned against Hitler. In brush-and-crayon lithographs, she portrays Death as a truculent skeleton. He wraps himself around a terrified woman; he seizes two children as a third attempts to flee; he taps the shoulder of someone—perhaps Kollwitz herself—who looks unbothered, ready to go. Later, the Nazis labelled her art “degenerate” and threatened to send her to a concentration camp. (They hated her politics more than the art itself: several of her prints were reproduced in Nazi journals.)

In the latter half of the twentieth century, Kollwitz’s images were appropriated by peace activists and studied by Black American artists such as Elizabeth Catlett and Charles White. “I like her feeling for people,” Catlett once said of Kollwitz. “I would love to do for black people what she did for poor German people, working people, if I could.” Kollwitz, like Catlett and White, has tended to find larger audiences when figuration is somewhat in vogue, as it is now. She knew how uncool it was, in her time, to use old-fashioned methods in the service of poor and working-class subjects, but she didn’t care. Whatever snobbish criticism came from the avant-garde, Kollwitz focussed on stretching the boundaries of printmaking to communicate ideas to a mass public. “Genius can probably run on ahead and seek out new ways,” she wrote, in her diary. “But the good artists who follow after genius—and I count myself among these—have to restore the lost connection once more.”

She believed that printmaking, as an elemental medium, could forge this human connection. (Early in her career, she had been influenced by the artist Max Klinger, who argued that printmaking was especially well suited to social critique.) She drew and engraved against war, and witnessed the advent of institutions meant to prevent it, yet the wars kept coming. Her figures have remained familiar because they recall so many tragedies—in Germany, Korea, Vietnam, Rwanda, Ukraine, and Palestine.

At MOMA, I could think only of the ashen devastation of Gaza. It wasn’t just Kollwitz’s gray-scale palette or the recurrence of hollowed-out eyes and stomachs. The woman in Kollwitz’s woodcut “The People,” covered in a black shroud, echoed the Palestinians who now wear their isdal around the clock, in preëmptive fashion. “If we die when our house is bombed, we want to have our dignity and modesty,” Sarah Assaad, a forty-four-year-old woman in Gaza, recently told Al Jazeera. “If we’re bombed and have to be rescued from the rubble, we don’t want to be rescued wearing nothing.”

I suspect that, were Kollwitz still alive, she would align herself, and her art of maternal grief, with the people of Gaza—and denounce the German government for punishing critics of Israel. But perhaps morality in art is as contingent as it is in law. Since last fall, when the contours of Israel’s campaign in Gaza became clear, the term jus cogens, Latin for “compelling law,” has often crossed my mind. Jus-cogens norms, which were articulated a half-century ago, prohibit mass murder and rape, apartheid, genocide, and slavery—the worst kinds of things people do to one another. They aren’t laws so much as “fundamental values of the international community,” according to the United Nations, which means that they apply to everyone, everywhere, no matter what, regardless of whether a treaty is signed. Beautiful but theoretical. Watching footage out of Gaza (but not only Gaza), I have wondered if any of this legal muttering matters at all.

As I proceeded slowly through the MOMA show, I noticed a woman to my right, bringing a magnifying glass close to one of Kollwitz’s antiwar prints. The viewer was dressed smartly, all in black. On her lapel was a pinned yellow ribbon, along with a strip of masking tape on which she’d written, in ballpoint ink, “182,” the number of days since Israeli hostages were taken by Hamas. What did this woman see in the show? Were she and I thinking about the same war, the same victims, the same mothers and children? ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com