Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The first enclosed shopping mall appeared in the United States in 1956, in Southdale, outside Minneapolis. The photographer Stephen DiRado was born a year later, and came of age as Southdale’s progeny reared up inexorably in suburbs across the country, exerting a hold on American consumer habits and social lives as insistent as the soft-pretzel-and-Cinnabon scent wafting from the food court. DiRado grew up in Marlborough, Massachusetts, near Boston, in a big, warm Italian American family. He was close to his father, a graphic artist who encouraged his precocious interest in photography, yet DiRado found it baffling that his dad was also a fan of the dreaded local mall. “I think he loved the architecture,” DiRado told me recently. “The city within a city, all the different levels and courtyards.” To young DiRado, the place was overwhelming, even terrifying. “It’s so artificial. It’s so cold. It has nothing to do with the organic stuff it was made of! Even at five, six, seven years old, I was just hyperventilating going shopping there.”

“Bernie and Bob, Tuesday, June 12, 1984.”

“Saturday Noon, April 27, 1985.”

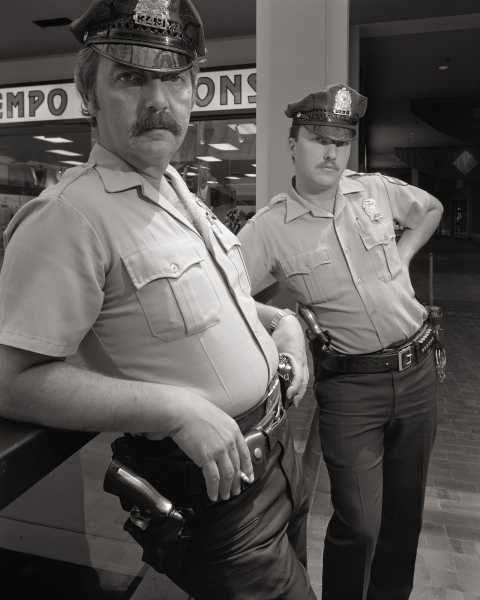

“Mall Security, Saturday Morning, July 19, 1986.”

“Teens with Boom Box, 1984.”

As a young photographer in the early eighties, DiRado established an approach that he would return to again and again. For months, or years, he’d immerse himself in a place that drew regulars into loose circles of camaraderie. His first major project documented the summer of 1983 at Bell Pond in Worcester, Massachusetts, an abandoned quarry with a small swimming beach that attracted working-class families and gangs of teen-agers. He’d hang around, get to know people, and sometimes offer to cook them dinner or walk their dogs. Then, at some point, he’d venture that he’d like to take their picture.

When DiRado starts shooting a project, he employs a bulky nineteen-fifties four-by-five view camera, duct-taped in places, and a tomahawk-style flash to light his subjects. Then he captures the moments he wants with a kind of magician’s misdirection. Disarmingly bubbly—with a Boston accent that renders his wife Donna’s name as “Dawner”—he chats away and maintains eye contact throughout the sessions, barely looking down to focus the camera. Despite, or somehow because of, his effusiveness, he often catches his subjects off guard, producing dramatically lit black-and-white images in which people look introspective or melancholy or emotionally undefended. DiRado is frank about the fact that many of his images are projections of his own anxieties. He always gives his portrait subjects prints of the photos but tells them, “Don’t be alarmed by what you see,” because they are as much about him as they are about them.

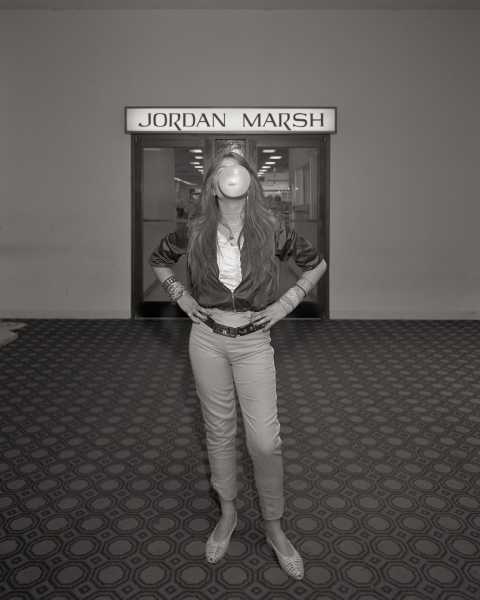

In 1984, DiRado decided that he wanted to chronicle mall life in America, confronting his old fears. “Overstimulation, loss of control—we’re all being manipulated in the mall,” he told me. “We know all that, of course, just like in casinos. Those colors on that sign—somebody thought about that to get you hungry or to buy stuff.” He picked the Worcester Center Galleria as his crucible, a one-million-square-foot mall built as part of an urban-renewal effort in 1971—which meant that, as a local journalist, Brian Goslow, has noted, it “wiped out and replaced nearly the entire downtown core.” By the early eighties, it was otherwise a classic American mall of its time: cavernous, multilevelled, with see-and-be-seen escalators; a fountain that smelled of chlorine and seemed vaguely amniotic (into which pranksters would periodically empty laundry detergent so that it overflowed with suds); wraparound railings that echoed satisfyingly if you banged on them; and all the usual kinds of retail, including a Filene’s, a Jordan Marsh, a record store, a Waldenbooks, and a place where you could get press-on logos for T-shirts that said things like “Disco Sucks” or “I’m with Stupid.” There was a dark, alluring pinball arcade; a giant, slightly scary parking garage; a movie theatre; a food court anchored by an Orange Julius. For two years, from late spring of 1984 to late summer of 1986, DiRado hauled his old camera and his spindly tripod to the Galleria, spending eighteen hours a week inside its self-enclosed, climate-controlled world. He recalls getting to the point where he could touch the front door and feel where the energy would be that day, and where to go first to set up his camera.

“Carol and John, 1984.”

“Joe and Noel, 1984.”

But DiRado’s vision of the mall as all hard, shiny surfaces and alienation was soon complicated by his encounters with the Galleria’s regulars. The corporations that ran the malls had been pulled between two imperatives: they wanted people to stay for a long time, but they also wanted to discourage loitering. Loitering was what teen-agers—“mall rats,” in the lingo of the eighties—did, and what mall cops were supposed to stop. Black and brown kids, along with skateboarders and punks, were particular targets. But loitering couldn’t be eliminated entirely because people who stayed long enough in a mall, even teen-agers, might, after all, buy something. A mall was a private space, though it functioned enough like a public street that ejecting people summarily could be tricky—sometimes even triggering lawsuits. In the meantime, loitering built community.

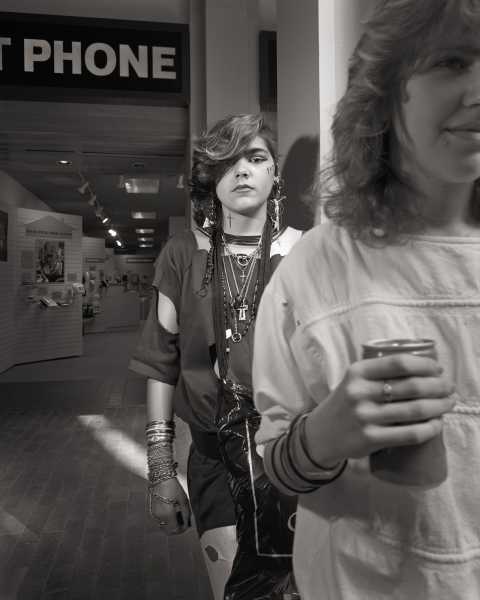

DiRado photographed young people who found one another in the mall and made it their refuge, particularly during the New England winter. In one photo, a bunch of teens crowd into the frame, in which somebody’s giant boom box takes pride of place. In others, kids show off carefully cultivated New Wave and punk ensembles and attitudes to match. Kim Nault—who, as a fifteen- and sixteen-year-old, appeared in several of DiRado’s photographs, sporting a fluffy mohawk and looking tough—lived in subsidized housing, in Worcester, and sang in a band. When I caught up with her recently, Nault, who now lives in California, told me, “Stephen’s photos captured a moment in history when bored and lonely teens had a common place to connect.” If she saw a punk kid walking around in the mall or being photographed by DiRado, she added, “I’d go up and introduce myself, ask them, ‘What kind of art do you do? Do you write? Are you a musician?’ ” When security would chase Nault and her friends out one entrance of the Galleria, they’d sneak back in through another.

It wasn’t only teen-agers who adapted the mall for their own communal purposes. DiRado also photographed elderly and disabled people who met up at the Galleria for coffee, companionship, or low-key coexistence with other generations. In one image, two dapper, older men have arranged themselves at a polite distance apart on a bench. In another, two older women, seated side by side and wearing matching glasses, peer appraisingly from behind the newspapers they’ve settled in to read. As the architecture critic Alexandra Lange writes in her history of shopping malls, “Meet Me by the Fountain,” from 2022, “Commercial imperatives accidentally created an architecture that accommodates those who often have the least societal power.”

“Ron, 1985.”

“Couple Behind Phone, Saturday, July 19, 1986.”

“Evening Gazette, June 29, 1986.”

“Father, Sleeping Baby on Fountain, 1984.”

That sense of inadvertent community is the main reason that DiRado’s photos elicit a certain nostalgia, almost in spite of themselves. (The excellent outfits might be another.) His images are certainly infused with his own sense of mall anxiety. There’s not a lot of laughter or smiling in them. The lighting often casts harsh or eerie shadows. Salespeople look dead-lonely or dead-bored, penned in by stuff. There’s a reason that the mall’s corporate honchos—who had signed a contract giving him free rein to document daily life there—“freaked out,” in DiRado’s words, when they first saw the results. Where was the evidence of all the fun that they sponsored? The clowns? The Santa Claus? But DiRado deliberately picked regular old days to park himself at the Galleria, and even if he encountered clowns or Santa Claus he surely wouldn’t have highlighted them at their cheeriest. Still, as he spent more time there, his original inspiration for the project, the dour black-and-white series “Suburbia,” by Bill Owens, receded and made room for another model: Brassaï’s nineteen-thirties work “Paris by Night.” Brassaï’s subjects—barflies, restaurant patrons, and the like—seemed more consciously performative and, in DiRado’s words, more “heroic.” The images DiRado was making became more vertical, with the subjects, not their backgrounds, dominating the frames. And he got to know and like many of the mall rats. “Stephen saw us as human beings and artists, not freak-show kids,” Nault said. (The suits later came around, too, and even helped underwrite a show of the work at the Worcester Art Museum.)

Malls have been in decline for many years now. Lange explains in her book that the problem was a glut of them—America just had so much space to build shopping centers, compared with other countries, and then along came Amazon and every other kind of online retail. The Worcester Galleria closed in 2006, and was subsequently demolished. If you happen to see a photography series on malls now, it’s probably centered on abandoned ones—images that traffic in unheimlich ruin porn, working the poignant seam where memories of ballyhoo meet obsolescence and decay. How shivery and sad it can feel to look at what’s left of these vaulting, vertiginous retail behemoths that seemed, like the Titanic, built to last. From the vantage point of our digital era, with its monetized suspicion of hanging out (Nest cameras, hysterical Nextdoor posts about teen-agers in hoodies) and its DoorDashing, remote-working, Internet-enabled social isolation, malls seem more benign than some of us imagined them to be in their prime—an IRL bonanza of fortuitous human encounters.

“Nancy, James, and Gina, December 14, 1985.”

“Lady Oris Hosiery, Saturday, April 6, 1985.”

“Sisters, Minnie and Gertrude, Saturday, June 30, 1984.”

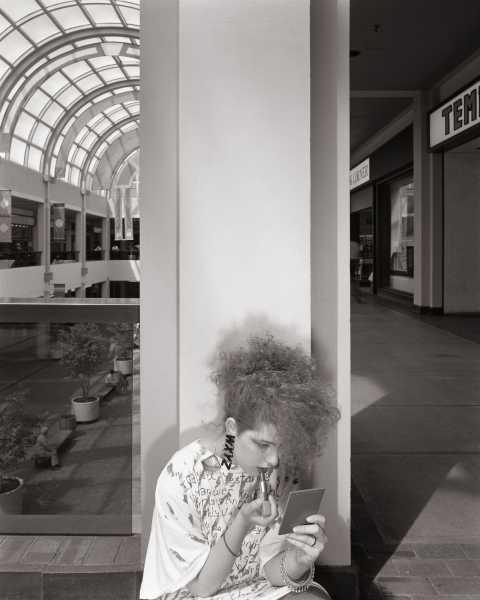

In the photo that graced the poster for DiRado’s show at the Worcester Art Museum, a young woman applies lipstick with a look of utter concentration. Her hair, an exuberant spill of eighties curls, makes a silhouette on the column behind her. The young woman is Cara Jean Cosenza. She wasn’t at the mall just to hang out; she was working two jobs, at two different stores, trying to save up money for college. But Cara, who went by Venus then, also wrote poetry and sewed her own clothes, and she thought of the Galleria as a place to show off her distinctive sense of style. In the shot, she’s wearing a dress made out of an oversized shirt, on which she had written all the lyrics to the Prince song “17 Days.” A long earring in the shape of the letters “WXYZ” dangles from one ear. DiRado took some more straightforward portraits of her that day, but he picked this one, in which Cara is preparing herself to be seen as she wants to be seen, finding an intimate moment within a vast, unintimate space.

“Venus, June 15, 1986.”

Cara, now Cara Marco, stayed in the Worcester area, where her parents owned a number of beauty salons. She grew up to be a school psychologist and administrator, work that she loves. “Spoiler alert,” she said at the beginning of a recent Zoom chat, “I turned out O.K.!” Cara said that she often thought the experience of being noticed and photographed by DiRado, and then seeing the image of herself hanging in the museum, on an opening night that felt red-carpet special for Worcester, was “a point of impact on my life,” encouraging her to strive for things she might not have otherwise. “It validated that internal voice, that omniscient narrator that played on a loop throughout my entire adolescence—you’re different, you’re special.” The mall had been her stage, as it had been for so many others, and DiRado had memorialized her turn upon it.

“Diane, Thursday Afternoon, July 5, 1984.”

“Nancy and Johanna, Day Before Madonna Came to Town, June 1, 1985.”

Sourse: newyorker.com