Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Though a year in movie releases is a small and arbitrary sample size, it’s nonetheless clear that, at the moment, the art of cinema is in good shape in the United States. The overwhelming commercial success of two of the year’s strangest big-budget films, “Oppenheimer” and “Barbie,” released on the same day this summer, is an obvious sign of the vigor of the cinemascape. But the more crucial indicator of vitality preceded their release by several years—namely, the moments when these projects got the green light from their respective studios. Both films’ subjects are as unusual as their styles: one is an existential exploration of a major figure in the worldwide expansion of American power, and the other is about a scientist. One has blown far beyond the billion-dollar mark, and the other is approaching it, at precisely the moment that the superhero-industrial complex seems to be tottering. But the studios are hardly the artistic center of the American cinema; they’re just one element in an environment that is fostering ongoing artistic progress.

A major reason for this creative energy is found behind the scenes, in the realm of production: the panoply of systems, which makes a wide range of movies in a wide range of ways. Even when the major studios have seemed to be choking on franchises, they have produced idiosyncratic releases; the year 2022 alone brought “Nope,” “Amsterdam,” and “Don’t Worry Darling.” Deep-pocketed streaming services that can afford to compete with the studios—and even outbid them—have an incentive to prove themselves as purveyors not just of quantity but of quality, including by competing for awards. As for independent production companies, they can—and must—take chances on inexperienced filmmakers with big ideas and on audacious projects by acclaimed filmmakers with the name recognition to help sell them.

This year’s best movies are bold undertakings both onscreen and off. Apple put up a whopping two hundred million dollars to make Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” which, notwithstanding its star power, was hardly a safe bet from a purely box-office point of view but is valuable to the company for the favorable publicity that it garners, for its direct potential to attract subscribers, and for its indirect potential to attract talent. Warner Bros. invested a hundred and forty-five million dollars to realize Greta Gerwig’s wildly decorative yet deeply considered take on Barbie, even though little in Gerwig’s two previous features, “Lady Bird” and “Little Women,” suggested the ability to pull off such an extravagant fantasy. Wes Anderson, who’s now an independent filmmaker working at a high level, made “Asteroid City” for just twenty-five million dollars; his madness is in his method, his ability to make such a film of vast scope on such a sub-studio (and sub-streaming) budget. Three films produced or co-produced by A24, on budgets largely unspecified but doubtless under ten million dollars, are all works of exceptional and daring artistry: “Showing Up,” “Earth Mama,” and, especially, “All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt,” which, from the strict perspective of inventive narrative form, is by far the most distinctive film of the year. (Next to it in originality are Anderson’s short Roald Dahl adaptations—produced by Netflix.)

The branch of the business that’s less vigorous at the moment is that of ultra-low-budget, do-it-yourself filmmaking. It’s the sector that, in the past two decades, has given rise to the careers of some of the most illustrious and original filmmakers of the time, such as Gerwig, Barry Jenkins, Terence Nance, Josephine Decker, and the Safdie brothers. They and others like them have revitalized American movies and the cinema at large. But success breeds its own troubles; in the past half-dozen years, I’ve noticed that the D.I.Y. sector has itself been in need of revitalization. Its early-two-thousands generation worked in an up-or-out world: a dismaying number of excellent filmmakers had trouble making careers; meanwhile, the successors of those who moved up haven’t yet emerged. It’s impossible to will a revolution, or any sort of innovation, into being.

From the perspective of the viewer, or even of the critic, a year in movies has a built-in unity—one cycle of releases—but those releases involve multiple years of production. Long gone are the days when John Ford directed three major movies (“Stagecoach,” “Young Mr. Lincoln,” and “Drums Along the Mohawk”) in a single year. Except for Hong Sangsoo (who has lately been averaging two movies a year, on scant budgets, sometimes with crews of only three or four people) or, this year, Anderson, most filmmakers are fortunate to make a movie every few years. The value—not necessarily of dollars in budget but of importance in a filmmaker’s career—of each film, of each given onscreen moment, is greatly increased, and much filmmaking has, as a result, grown tight.

What’s missing from even most of the best American films is a sense of swing, for exactly this reason: swing is a matter of spontaneity, and movies that are years in the making tend to have less of it. (The new movie in which I find the most of it is “Passages”—by the American director Ira Sachs, who made it in Paris mostly with European actors.) Even the fact that shooting schedules are painfully short, for economic reasons, exacerbates the problem; when directors with an ample cast and crew have to work very fast, they also require extremely precise planning. The flipside of this loss of spontaneity is that filmmakers have time to think about what they’re doing and where they stand in regard to it. (Scorsese’s drastic preproduction transformation of “Killers of the Flower Moon” is a prime example.) As it happens, this reflectiveness is very much in tune with the politics of the time, which often spotlights the position of filmmakers in relation to the world they depict—a tendency abetted by social media, with its expanded range of critical discussion.

As fierce or stringent as the political cinema of earlier generations may be, what seems to distinguish the current version is a sense of mirroring, of dramatizing not just an inner world but the standpoint from which it’s conceived. The strongest political insights of today’s movies involve a word that has become ubiquitous in the attempt to understand inequality and injustice (and that has, as a result, become a target of the censorious right): “systemic.” Filmmakers working at opposite ends of the budgetary spectrum, such as Gerwig with “Barbie” and Savanah Leaf with “Earth Mama,” do more than take on political subjects; they find ways, whether exuberantly comic or tensely dramatic, to connect their protagonists’ conflicts to institutions. Anderson has always been a filmmaker of revolt, and in “Asteroid City” he presents a confectionary version of the military-industrial complex, the paranoid repression that it helped to enforce in the nineteen-fifties, and the spirit of defiance that motivates young prodigies—and even some mid-career artists.

The particularity of the current political moment can be seen if one compares the tag scene at the end of Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon” with the one at the end of a film he made a decade ago, “The Wolf of Wall Street.” In the earlier one, Scorsese implicates the world at large in the moral failings depicted in the film; in the new one, he implicates himself personally. Yet as the personal cinema moves—all to the good—from self-celebration to self-questioning, its tone changes. That may be a reason for the decline in D.I.Y. filmmaking. The sense (or the illusion) of working outside or without established systems doesn’t favor the display of a system’s workings. At such a moment, ingenuous artists risk seeming naïve—unless, like the now established generation of once independent filmmakers, they aim at a radical transformation of the world of movies and actually achieve it.

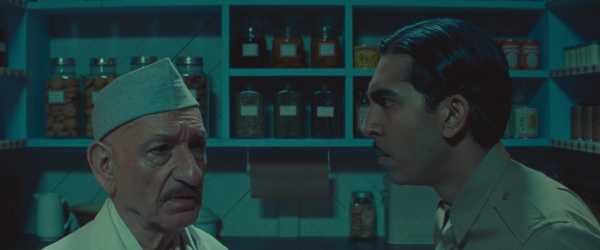

Photograph by Melinda Sue Gordon / Courtesy Apple TV+

1. “Killers of the Flower Moon”

Martin Scorsese’s vast adaptation of David Grann’s nonfiction investigation of the violent encroachment of white Americans on the oil wealth of the Osage Nation unpacks American history as a widespread criminal conspiracy and distills it into a drama of marital mysteries as disturbing and resonant as those of “Eyes Wide Shut.”

2. “Asteroid City”

Wes Anderson’s exquisitely filigreed and ardently romantic view of a grieving family and a lonely actress at the science-fiction-adjacent setting of a young astronomers’ conference mines the weirdness of the nineteen-fifties—an enduring and still active complex of troubles and tropes hiding in plain sight in the era’s movies and in its political paranoia.

3. “Barbie”

The irrepressible outpouring of giddy but principled inspiration in Greta Gerwig’s blockbuster—a vision of the earnest passions embodied in child’s play and the progressive power of girls’ uninhibited imagination—feels like the first display of her comprehensive artistry and like a new dimension in modern cinema.

4. “All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt”

Spanning half a century in the life of a woman in rural Mississippi, Raven Jackson’s first feature unites family lore and the legacy of history with a breathtaking romantic melodrama—and does so with a bold command of time and intensely sensitive image-making.

5. “Showing Up”

From the modest premise of a sculptor preparing her work for a show while also working at an art school, Kelly Reichardt explores the bonds and the conflicts of a tight-knit community, the burdens of family, and the inescapably fruitful frustrations of life’s impingement on art. The depths of an artist’s soul have rarely been filmed as finely.

Photograph courtesy MUBI

6. “Passages”

The American filmmaker Ira Sachs’s turbulent melodrama set in Paris—in which a German movie director married to a British man embarks on a reckless romance with a French woman—unleashes torrents of violently mixed emotions and yields a vertiginous, ecstatic sense of liberation.

7. “Civic”

There’s a feature film’s worth of style and experience crammed into the twenty-minute span of Dwayne LeBlanc’s first film, a classic tale of a young man’s return home (to South Central Los Angeles) conveyed with an audacious and original sense of form.

8. “A Thousand and One”

A. V. Rockwell’s first feature, spanning about two decades in the life of a mother and child in Harlem, fiercely depicts the ardor of family life and the fragility of family ties amid political pressures on the community, including oppressive policing, gentrification, and the trauma of incarceration.

9. “Earth Mama”

Savanah Leaf’s début feature, the drama of a young woman’s fervent efforts to regain custody of her children and to maintain a bond with her newborn, offers some of the most expressive closeups in recent movies, along with a sharply detailed analysis of bureaucratic obstacles to the legal unity of families that Black women face.

10. “Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game”

For their first feature, the brothers Austin and Meredith Bragg dramatize an extraordinary byway of history: the longtime illegality of pinball in New York City and its legalization, in the mid-seventies, through the efforts of a journalist who loved the game. The film employs a daring narrative framework to present a bittersweet, vibrantly scrappy re-creation of the times.

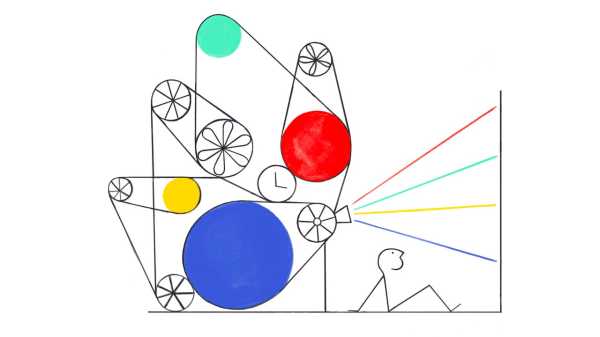

Photograph courtesy Netflix

11. “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,” “The Swan,” “The Rat Catcher,” “Poison”

With this quartet of short films adapted from stories by Roald Dahl, Wes Anderson invents a new kind of cinematic storytelling—characters are both onscreen narrators and participants in the action—and portrays the cruelties of Dahl’s world as those of life at large.

12. “Menus-Plaisirs—Les Troisgros”

For his forty-fourth documentary, the nonagenarian filmmaker Frederick Wiseman embeds with the chefs of a three-star French restaurant. Filming trenchantly and editing daringly, he uncovers the vast range of knowledge (scientific and culinary), experience (artisanal and administrative), and passion (artistic and personal) that energizes the enterprise—and finds the place of haute cuisine in the cultural pantheon.

13. “Petite Solange”

The coming-of-age story of a teen-age girl in a small French city against the backdrop of her parents’ divorce gets both a melodramatic twist and a classical grandeur through Axelle Ropert’s poised and discerning direction.

14. “Ferrari”

Now in his eighties, Michael Mann makes his best film in decades with this grandly romantic yet death-haunted biographical story about Enzo Ferrari’s effort, in the fifties, to rescue his company by winning a major auto race.

15. “Orlando, My Political Biography”

The philosopher Paul B. Preciado’s first film, a docufictional and reflexive adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s historical fantasy “Orlando,” features more than twenty trans or gender-nonconforming actors in the title role. Integrating their personal reflections into Woolf’s story, the filmmaker pulls its drama into the present tense and even into a visionary future.

16. “Walk Up”

The prolific South Korean director Hong Sangsoo, working cheaply and spontaneously, delivers one of his most wide-ranging stories—of family conflicts and long-lost friends, the frustrations of filmmaking and the passion of art, the bewilderment of youth and the burden of age—in and around a single multistory building in Seoul.

17. “Origin”

To dramatize the real-life story of how the journalist Isabel Wilkerson wrote her nonfiction book “Caste,” the director Ava DuVernay boldly blends the contours of a bio-pic with documentary-based aspects of the author’s research.

Photograph courtesy A24

18. “Priscilla”

The life of Priscilla Presley, as overshadowed in adolescence by Elvis’s attention and in adulthood by his inattention, is presented by Sofia Coppola as a poignant synecdoche for the subordination of women in the culture at large.

19. “The Color Purple”

The director Blitz Bazawule, with his second feature, approaches the Broadway razzle-dazzle of the stage musical with stylish inspiration and gets hearty, exuberant, grounded performances from his superb cast.

20. “Our Body”

Claire Simon’s documentary, set in the gynecology ward of a French hospital, explores a vast range of women’s-health and gender-related concerns, including abortion and gender confirmation, and looks closely at the invasive intricacies of medical technology—as well as the filmmaker’s own treatment there for a serious illness. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com