Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

This year’s literary pilgrimage was to Hadlyme Cove Cemetery, in Connecticut, where Edith Hamilton is buried, along with her sister Alice Hamilton, who would have been the more famous of the sisters—she began her career as a professor of pathology at Northwestern University and was the first woman on the faculty of Harvard University—if Edith’s books on Greek and Roman mythology, written after she retired from teaching, had not been a publishing phenomenon.

There were four Hamilton sisters. They grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and were industrious and cosmopolitan, pursuing higher education at institutions around the world. When Alice was in her late forties, she bought a house on the Connecticut River, overlooking the seasonal ferry between Hadlyme and Chester, so that the family would always have a place to gather. Edith moved around—from Baltimore to New York to Maine to Washington, D.C.—with her partner, Doris Fielding Reid. The other sisters, Margaret and Norah, are also buried at Hadlyme Cove, along with their mother, Gertrude Pond Hamilton. Both Margaret’s lifetime partner, Clara Landsberg, and Reid are buried there as well. The women’s headstones, chiselled from the traditional flinty-looking local stone, are arrayed in a long, dignified arc. Edith’s is the only one that looks to have been recently cleaned.

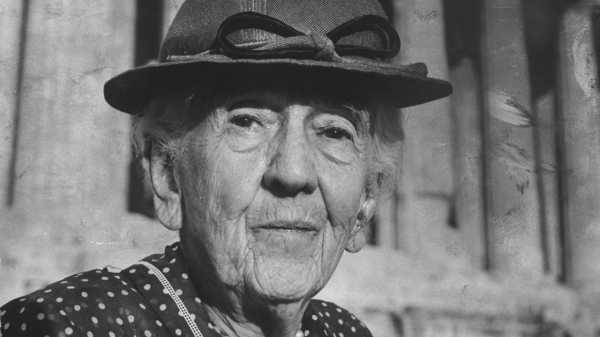

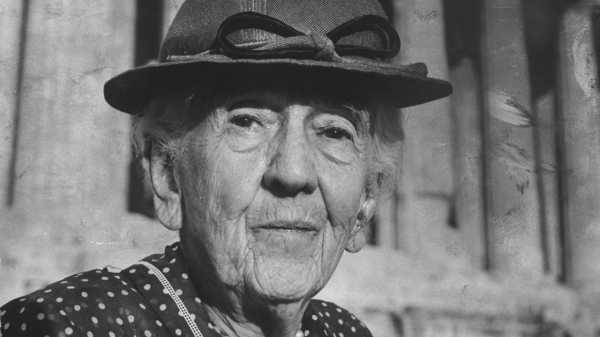

The occasion for the pilgrimage was a new biography, “American Classicist: The Life and Loves of Edith Hamilton,” by Victoria Houseman. The title struck me as funny at first—in her author photos, Hamilton looks every bit the old maid (if one may still use that term), thin and rather sharp-featured—but the book is surprisingly juicy. Growing up with sisters and girl cousins, who stayed close all their lives, Hamilton was comfortable in the company of women. She went to Miss Porter’s School and Bryn Mawr College, the women’s school near Philadelphia that is famous for turning out classicists and classical archeologists, and had hoped to earn a Ph.D. and have an academic career. Instead, she took a job as the headmistress of the Bryn Mawr School, a preparatory school for girls, in Baltimore. Back in Indiana, her father, Montgomery Hamilton, had suffered some business disappointments (he failed to become president of the family bank) and took to drink; the money for his children’s education was running short, and Edith took the teaching job.

In Baltimore, Hamilton met the Reid family—Edith Gittings Reid, a prominent society hostess, and Harry Fielding Reid, a professor of geology at Johns Hopkins—who took such a liking to her that they invited her to live with them. Their daughter, Doris, was two years old when Hamilton entered the family circle. Doris later attended the Bryn Mawr School but left to study piano. She later wrote the first biography of Hamilton—“Edith Hamilton: An Intimate Portrait” (1967)—which tells how Hamilton began spending summers with the Reid family on Mount Desert Island, Maine. In Doris Reid’s telling, Hamilton suffered from some unspecified ailment. (Houseman reveals that it was breast cancer; Hamilton was treated and lived to the age of ninety-five.) Some years ago, having read Reid’s book, I tried to find Sea Wall, where Hamilton and Reid first set up housekeeping together. This area of Maine, near Southwest Harbor, is so bewitchingly beautiful that I suspected Hamilton suffered from nothing so much as having to leave it at the end of the summer. She and Reid spent the winter of 1923-24 together at Sea Wall, with Reid’s nephew Dorian, whom they adopted. (The adoption provides the one disquieting moment in the biography; the birth mother’s feelings seem to have been sacrificed.) The following fall, they moved to New York and lived in Gramercy Park. By this time, Hamilton was no longer in charge of the Bryn Mawr School, but if she did now what she had done then—move in with a former student twenty-eight years her junior—Edith Hamilton would be so cancelled.

Houseman opens her biography with the twenty-one-year-old Edith Hamilton writing to her cousin Jessie about a performance of Sophocles’ “Electra” in 1889. Thirty-seven years later, in 1926, tragedy was the subject of her first published essay in Theatre Arts Monthly. It attracted the attention of an editor at W. W. Norton, which published a collection of her essays under the title “The Greek Way” (1930). The book was such a success for Norton, a young firm at the time, that it was soon followed by “The Roman Way” (1932). Hamilton’s writing, unencumbered by scholarly apparatus, seems to rise spontaneously from deep knowledge and love of her subject. Her translations of “Prometheus Bound,” “Agamemnon,” and “The Trojan Women” were published by Norton under the title “Three Greek Plays” (1937). Hamilton’s “Mythology” (1942), conceived by an editor at Little, Brown to replace the venerable “Bulfinch’s Mythology” as a reference book for the general reader, has yet to be supplanted. Her writing is lucid and her tone is warm; in her telling, certain myths, such as the one about Demeter and Persephone, are powerfully moving. Houseman writes that she came to be regarded as “an accomplished classicist gifted with a unique ability to clearly communicate her interpretation of the ancient world to others.”

The new biography offers much speculation on the relationship between Hamilton and Reid: was it romantic, sexual, or pragmatic? They slept in separate bedrooms. The only evidence Houseman turns up that they may have slept together is in a letter from Hamilton to her cousin Jessie thanking her for the gift of a horsehair mattress. One friend suggested that Reid played Boswell to Hamilton’s Johnson. It’s clear that their relationship was loving and supportive and that it evolved organically. Hamilton needed the stability of a family to free her to work. Houseman notes that Hamilton had never been eager to marry. She did not see the point in marriage if it meant sacrificing the things she loved—time with her sisters and cousins, her studies, her travels in Europe and Asia with family and friends, the things that made her her—in order to subordinate herself to some man whom she may have known for only a few years.

Reid eventually became a successful stockbroker; her work took them to Washington, D.C. Hamilton continued to write, turning her attention to the prophets of the Old Testament and the life of Christ, and she co-edited a volume of Plato in translation. She had become hard of hearing and would turn off her hearing aid to concentrate. Her book “The Echo of Greece” was published in 1957. That same year, her translation of “Prometheus Bound” was performed at the Herodes Atticus Theatre, at the foot of the Acropolis, and Hamilton, who was present on the occasion, was made an honorary citizen of Athens. What more could a philhellene want?

A Ph.D. in classics, that’s what. Houseman stresses that Hamilton earned the respect of the academy despite her lack of academic credentials—she had honorary doctorates from Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Rochester, and was twice invited to address the Classical Association of the Atlantic States—but there is a lingering sense that she was never fully admitted to the club. The knock on her scholarship seems to be that she used classical Greece to promote her own political views, or vice versa. She was an early supporter of women’s suffrage and a committed pacifist. Chances are that if she had not pointed out the relevance of the classics to her own time, which included the rise of Nazism, she would have been criticized for that. It is easy to suppose that academics begrudged her the book sales; her most scholarly book sold the fewest copies. The saddest moment of Houseman’s biography comes near the end, when Hamilton accepts the mantle of “popularizer.” As Professor Yogi Berra might have put it, nobody likes a popularizer.

Full disclosure: I, too, have written about Greek from outside the academy, and for the same publisher, W. W. Norton, though I never came near either Edith Hamilton’s scholarship or her sales. I am still waiting for the honorary degree and the house in Maine. I am in awe of classical scholars and the tradition that has given us the texts. Houseman’s book itself, published by Princeton University Press, is a superb example of a scholarly biography, highly readable, with a helpful chronology at the front and more than a hundred pages of notes and bibliography at the back. Hamilton led a rich and useful life and, what’s more, she found domestic happiness. Perhaps the clue to her success lies in the dedication of her first book, “The Greek Way”—“To Doris Fielding Reid: Κοινὰ τὰ τῶν φίλων,” literally “Common [are] the things of friends,” which might be loosely rendered as “This is as much yours as it is mine.” Reid made Hamilton’s rebirth as a writer possible. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com