Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

When I heard on Saturday that Jimmy Buffett had died, I wrote a condolence e-mail to his longtime friend Thomas McGuane, the novelist. McGuane, who is married to Buffett’s sister Laurie, was the go-between when I was trying to get Buffett to talk to me last year, when I was reporting a story about Latitude Margaritaville, the retirement community, or communities, really, that are, notionally, a manifestation of the beachy/breezy/boozy ethos expressed in his songs. Buffett had got rich and even more famous by converting his body of work into a life-style brand. That success, the freedom it gave him to say no, and maybe some lingering if unacknowledged misgivings over the relationship of his attainments in business to his songwriting made him squirrelly about interviews, or this one anyway. McGuane, who referred to Buffett as Bubba, put in a word. Bubba and I Zoomed. He was delightful.

McGuane, in his reply on Sunday, wrote that he’d just returned from Telluride, where he’d helped introduce a new documentary about Buffett and their friends, and their lives as artists and fishermen in Key West a half century ago. It is called “All That Is Sacred” and is directed by Scott Ballew. (The film has yet to find a distributor.) Buffett was supposed to have been in Telluride, too, but, alas, he lay dying, at his home in Sag Harbor, on Long Island. Of the people featured in the film—among them Jim Harrison, Richard Brautigan, Russell Chatham—McGuane was now the lone survivor. “There were two of us left at the Friday showing, and by Saturday I was it,” he wrote.

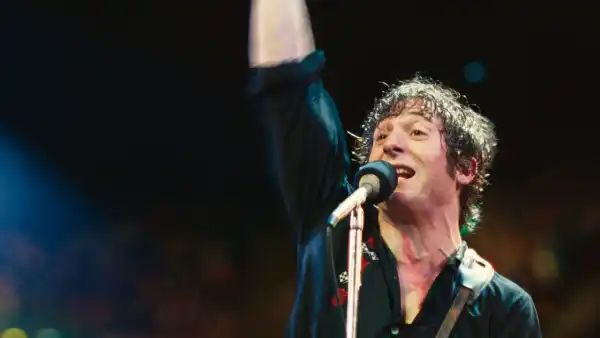

In the film, McGuane says that he hates old photographs and generally disdains nostalgia. “All That Is Sacred,” just a half hour long, is a taut refutation, or at least a balm to anyone who might disagree. The film relies on footage from an older documentary called “Tarpon,” made in 1973, by Guy de la Valdene and Christian Odasso, but for many years seen by pretty much no one. (Though never released, bootlegs of it eventually turned it into a bonefish bum’s variation on the 1972 cult surf film “Morning of the Earth.”) It chronicled the Key West scene, focussing more on the fishing than the writing. On the basis of the tarpon footage alone, shot by a French crew that erected a platform in the flats, it’s a gem, but the many youthful glimpses of Harrison, with his gap-toothed, mangle-eyed grin, and McGuane, with his long hair and sly smile, and Buffett, very much still the authentic embodiment of the sand-pirate fantasia he’d soon be known for creating, evoke, as the film puts it, a kind of hippie Algonquin Round Table. The men were serious about their work, and perhaps even about their fishing, but profligate in their leisure-time habits. Tequila, pot, cocaine, acid, ’ludes. The vibes were heavy but the tourist traffic was light. What a time to be alive.

“You kind of have these congeries of people who get together for one reason or another, and then the astonishing thing about growing old is that people basically disperse,” McGuane, now eighty-three and living in Montana, says in “All That Is Sacred.” “We’re lucky to have had it happen. Most of us feel those were the best years of our lives.” (Nostalgia? Very well then, he contradicts himself.)

Buffett did the soundtrack to “Tarpon.” He was more or less a nobody at the time, a Nashville washout playing for beers in the local bars. But he was also about to release “A White Sport and a Pink Crustacean,” his second album (not counting a bluegrassy album that didn’t see a release until many years later), and the one that got him going. Or that got him enough money, anyway, to buy a boat. He slowly built an audience, on the basis of the songs and his ease and charm at performing them. It was the experiences of that time in Key West that created the fodder and the spirit for a vast body of work and eventually a Parrothead empire. It was an essential metamorphic stage in his splendid and uniquely American journey from Mobile, Alabama, and the bars of New Orleans to his own mega-Margaritaville, his version of which ultimately involved boats and planes and friends in high places. He seems to have left no ill will in his wake.

In life and in death, the kitsch and the shtick have often overshadowed the songwriting on those earlier albums—say, the first six, or ten. He’s one of those artists about whom it is possible to say that he has been both underrated and overrated. His fame and fortune, and the goofiness of the Parrothead sacraments, may have made him an easier target of some critical snickering, or outright dismissal; honors and awards and best-of backpats mostly eluded him. I’m guilty of it, too. As I wrote in my story last year, “A poor man’s Gordon Lightfoot grows into a drinking man’s Martha Stewart, hardly having to change his tune.” But the songcraft was sturdy, the words deft and, beneath the celebratory hedonism, often sorrowful and wise. Other artists whose work has been taken more seriously—from Paul McCartney to James Taylor to Jason Isbell—have had nothing but lovely things to say about the work and the man. Not every dude with a guitar needs to be Lou Reed.

On Sunday night, down in Daytona Beach, at Latitude Margaritaville, the residents held a vigil outside the house Buffett owned there. They’d made a little shrine, with a surfboard, a straw hat, flowers, a bottle of premixed margarita, and a Jimmy Buffett for President T-shirt. I reached out via text to two guys who’d schooled me in pickleball when I’d visited the grounds, in December, 2021—Hershey McChesney and Allen Farkas.

“He created a world that the everyday guy could escape to, with his music,” McChesney replied. “For the people here it has become a reality. And it never would have happened without him.”

Farkas texted that he’d have to skip the vigil. “Have a few for me, Hersh. I have my fantasy draft tonight.”

As John Cohlan, the chief executive of Margaritaville Holdings and a friend of Buffett’s, wrote to me, about a newspaper tribute that he thought had nailed it, “No rearview mirror. That’s Jimmy.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com