Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

I belong to the last generation of Americans who grew up without the Internet in our pocket. We went online, but also, miraculously, we went offline. The clunky things we called computers didn’t come with us. There were disadvantages, to be sure. We got lost a lot. We were frequently bored. Factual disputes could not be resolved by consulting Wikipedia on our phones; people remained wrong for hours, even days. But our lives also had a certain specificity. Stoned on a city bus, stumbling through a forest, swaying in a crowded punk club, we were never anywhere other than where we were.

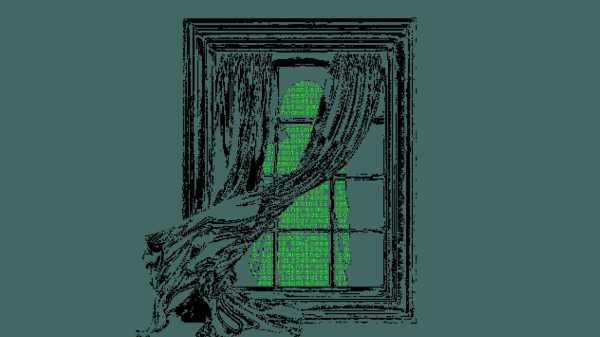

Today, it is harder to keep one’s mind in place. Our thoughts leak through the sieve of our smartphones, where they join the great river of everyone else’s. The consequences, for both our personal and collective lives, are much discussed: How can we safeguard our privacy against state and corporate surveillance? Is Instagram making teen-agers depressed? Is our attention span shrinking?

There is no doubt that an omnipresent Internet connection, and the attendant computerization of everything, is inducing profound changes. Yet the conversation that has sprung up around these changes can sometimes feel a little predictable. The same themes and phrases tend to reappear. As the Internet and the companies that control it have become an object of permanent public concern, the concerns themselves have calcified into clichés. There is an algorithmic quality to our grievances with algorithmic life.

Lowry Pressly’s new book, “The Right to Oblivion: Privacy and the Good Life,” defies this pattern. It is a radiantly original contribution to a conversation gravely in need of new thinking. Pressly, who teaches political science at Stanford, takes up familiar fixations of tech discourse—privacy, mental health, civic strife—but puts them into such a new and surprising arrangement that they are nearly unrecognizable. The effect is like walking through your home town after a tornado: you recognize the buildings, but after some vigorous jumbling they have acquired a very different shape.

Pressly trained as a philosopher, and he has a philosopher’s fondness for sniffing out unspoken assumptions. He finds one that he considers fundamental to our networked era: “the idea that information has a natural existence in human affairs, and that there are no aspects of human life which cannot be translated somehow into data.” This belief, which he calls the “ideology of information,” has an obvious instrumental value to companies whose business models depend on the mass production of data, and to government agencies whose machinery of monitoring and repression rely on the same.

But Pressly also sees the ideology of information lurking in a less likely place—among privacy advocates trying to defend us from digital intrusions. This is because the standard view of privacy assumes there is “some information that already exists,” and what matters is keeping it out of the wrong hands. Such an assumption, for Pressly, is fatal. It “misses privacy’s true value and unwittingly aids the forces it takes itself to be resisting,” he writes. To be clear, Pressly is not opposed to reforms that would give us more power over our data—but it is a mistake “to think that this is what privacy is for.” “Privacy is valuable not because it empowers us to exercise control over our information,” he argues, “but because it protects against the creation of such information in the first place.”

If this idea sounds intriguing but exotic, you may be surprised to learn how common it once was. “A sense that privacy is fundamentally opposed to information has animated public moral discourse on the subject since the very beginning,” Pressly writes. Only in the past several decades, through a mechanism he does not specify, did this anti-informational definition of privacy begin to fade. But it “is not lost completely,” he insists: traces of it persist in our moral intuitions about what, exactly, is bad about the information age. The ambition of Pressly’s book is to recover and reconstruct this older way of thinking about privacy. He begins by taking us back to the historical moment when it arose, a time of technologized upheaval even more bewildering than our own: the late nineteenth century.

In 1888, George Eastman, a former bank clerk from Rochester, New York, started selling a camera that you could easily hold in your hands. He called it the Kodak. It was simple to use and came with a film roll that could fit a hundred pictures. Within a decade, Eastman had sold 1.5 million of them.

As a technology, photography had existed for decades. But Eastman made it portable and affordable. (His first camera cost $25, around $825 in today’s dollars. The Kodak Brownie, introduced in 1900, only cost $1, or about $37 today.) In doing so, he created a new kind of guy—the amateur photographer. Swarms of Kodak-wielding shutterbugs descended on American cities, thrusting their lenses in front of flustered strangers. A discourse soon developed about the evils of this phenomenon. “Photographers were commonly referred to as a scourge, lunatics, and devils: ‘kodak fiends driving the world mad,’ ” Pressly writes.

Theodore Roosevelt had a particular loathing for Kodak fiends. As President, he even banned cameras, briefly, from the parks of Washington, D.C. In 1901, when a teen-ager tried to take a picture of him as he left a church, he yelled at the boy to stop. A nearby police officer intervened. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself!” the officer told the young photographer, as recounted by a journalist who witnessed the scene. “Trying to take a man’s picture as he leaves a house of worship. It is a disgrace.”

This is the language of moral outrage. For Pressly, such outrage was inspired, at least in part, by the belief that being photographed can compromise one’s autonomy.

We don’t get to decide what will be revealed; the photographer does. A camera commits our likeness to celluloid, making it reproducible, and that means it can circulate in ways beyond our knowledge and control, and be put to work for purposes that are not our own. Pressly tells the story of Marion Manola, an actress who sued a photographer, in 1890, for taking a picture of her during a performance. She wasn’t “embarrassed to be seen in costume, nor did she think that her concealment or secrecy had been broached,” Pressly writes. “Rather, Manola’s complaint was that by printing and displaying the photograph, the photographer forced her to appear in places and circumstances against her will.” (She won the lawsuit.)

The same year, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis published an article called “The Right to Privacy.” This short text, which would go on to enjoy wide influence as the founding document of modern privacy law, called for a new right to privacy, citing the Manola case, among others. Significantly, the authors defined this right in expansive terms, as “the right to one’s personality.” By this, they meant that we should not be compelled to disclose anything about ourselves that we would prefer to keep out of the public eye. Photography, they believed, could have a coercive aspect: its invasion of privacy was an infringement of agency, analogous to a forced confession.

Such a view may seem quaint in the third decade of the twenty-first century, with the ubiquity of smartphones and CCTV cameras. But the Victorian critique of photography, as excavated and elaborated by Pressly, was also a critique of information, and this makes it distressingly applicable to our present. Digitization has industrialized the process of data-making. The impertinence of the Kodak fiend has become a vast, invisible apparatus of computation that is perpetually grinding data from the grist of our daily affairs, and exploiting such information for all sorts of ends. Like our Victorian forebears, we are not consulted about the enterprises in which our information enlists us. The difference is that, in 2024, there is so much more that information can do.

Consider, for example, the growing popularity of deepfake nudes among schoolchildren across the country. In recent years, groups of boys in multiple states have used generative-A.I. software to produce artificial naked images of female classmates. To create such images, two kinds of information are required: a genuine (clothed) photograph of the individual you wish to undress and millions of photographs of naked women, scraped from various online sources, which make up the data sets on which the A.I. system was trained.

This is an especially grim illustration of Pressly’s argument about how the production and the circulation of information can undermine our agency. The person targeted by the deepfake did not consent; neither did the masses of anonymous others whose bodies taught a computational model how to make a plausible simulacrum of nakedness. The result is obscene, but the underlying logic is the modus operandi of our algorithmic age. If one defining feature of contemporary digitization is the abundance of information created by us and about us—without which targeted advertising would cease to exist, and ChatGPT wouldn’t be able to sound like a human being—another is that we have little to no say in how this information is used. For Pressly, real privacy would mean not simply enabling people to participate in such decisions but mandating that far less data be made in the first place. Brought to its logical conclusion, his proposal evokes a kind of digital degrowth, a managed contraction of the Internet.

I have to confess something: I find privacy boring. When I first received Pressly’s book, I groaned. Within the first few pages, I realized my mistake. The highest compliment I can pay “The Right to Oblivion” is that it rescues privacy from the lawyers. Pressly’s version of privacy has a moral content, not just a legal one. And this gives it relevance to a broader set of intellectual and political pursuits.

There is a wealth of scholarship on surveillance. Simone Browne has described its racial and racist dimensions, and Karen Levy and others have examined how digital monitoring can discipline and disempower workers. But privacy is rarely the central preoccupation in this work; other concerns, such as justice and equality, figure more prominently. With Pressly, however, privacy is defined in such a way as to seem vital to such critiques. Lawyers like to make privacy about process. Pressly makes it about power.

If that were everything the book did, it would be enough. But “The Right to Oblivion” is actually much stranger than my summary thus far suggests. The reason that Pressly feels so strongly about imposing limits on datafication is not only because of the many ways that data can be used to damage us. It is also because, in his view, we lose something precious when we become information, regardless of how it is used. In the very moment when data are made, Pressly believes, a line is crossed. “Oblivion” is his word for what lies on the other side.

Oblivion is a realm of ambiguity and potential. It is fluid, formless, and opaque. A secret is an unknown that can become known. Oblivion, by contrast, is unknowable: it holds those varieties of human experience which are “essentially resistant to articulation and discovery.” It is also a place beyond “deliberate, rational control,” where we lose ourselves or, as Pressly puts it, “come apart.” Sex and sleep are two of the examples he provides. Both bring us into the “unaccountable regions of the self,” those depths at which our ego dissolves and about which it is difficult to speak in definite terms. Physical intimacy is hard to render in words—“The experience is deflated by description,” Pressly observes—and the same is notoriously true of the dreams we have while sleeping, which we struggle to narrate, or even to remember, on waking.

Oblivion is fragile, however. When it comes into contact with information, it disappears. This is why we need privacy: it is the protective barrier that keeps oblivion safe from information. Such protection insures that “one can actually enter into oblivion from time to time, and that it will form a reliably available part of the structure of one’s society.”

But why do we need to enter into oblivion from time to time, and what good does it do us? Pressly gives a long list of answers, drawn not only from the Victorians but also from the work of Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Gay Talese, Jorge Luis Borges, and Hannah Arendt. One is that oblivion is restorative: we come apart in order to come back together. (Sleep is a case in point; without a nightly suspension of our rational faculties, we go nuts.) Another is the notion that oblivion is integral to the possibility of personal evolution. “The main interest in life and work is to become someone else that you were not in the beginning,” Foucault writes. To do so, however, you must believe that the future can be different from the past—a belief that becomes harder to sustain when one is besieged by information, as the obsessive documentation of life makes it “more fixed, more factual, with less ambiguity and life-giving potentiality.” Oblivion, by setting aside a space for forgetting, offers a refuge from this “excess of memory,” and thus a standpoint from which to imagine alternative futures.

Oblivion is also essential for human dignity. Because we cannot be fully known, we cannot be fully instrumentalized. Immanuel Kant urged us to treat others as ends in themselves, not merely as means. For Pressly, our obscurities are precisely what endow us with a sense of value that exceeds our usefulness. This, in turn, helps assure us that life is worth living, and that our fellow human beings are worthy of our trust. “There can be no trust of any sort without some limits to knowledge,” Pressly writes.

When we trust someone, we do so in the absence of information: parents who track their children’s whereabouts via G.P.S. do not, by definition, trust them. And, without trust, not only do our relationships go hollow; so, too, do our social and civic institutions. This is what makes oblivion both a personal good and a public one. In its absence, “an egalitarian, pluralistic politics” is impossible.

Oblivion is a concept with a lot of moving parts. It is a testament to Pressly’s gifts as a writer that these parts hang together relatively well. For an academic, he takes unusual care with the construction of his sentences. He has published several short stories, and you can tell: his prose often exhibits the melody and the discipline of fiction. But he is also very much a philosopher, trained in the specific combat of the seminar room. He spends a lot of time anticipating possible objections and sorting ideas into types and subtypes.

Yet, while Pressly alternates between the literary and the analytic, he makes surprisingly little use of the tradition that synthesizes the two—psychoanalysis. Freud and his followers are a minimal presence in “The Right to Oblivion,” despite the fact that oblivion bears an obvious resemblance to the unconscious and that Pressly, in trying to theorize it, faces a familiar psychoanalytic predicament: how to reason about the unreasonable parts of ourselves.

Psychoanalysis first emerged in the late nineteenth century, in parallel with the idea of privacy. This was a period when the boundary between public and private was being redrawn, not only with the onslaught of handheld cameras but also, more broadly, because of the dislocating forces of what historians call the Second Industrial Revolution. Urbanization pulled workers from the countryside and packed them into cities, while mass production meant they could buy (rather than make) most of what they needed. These developments weakened the institution of the family, which lost its primacy as people fled rural kin networks and the production of life’s necessities moved from the household to the factory.

In response, a new freedom appeared. For the first time, the historian Eli Zaretsky observes, “personal identity became a problem and a project for individuals.” If you didn’t have your family to tell you who you were, you had to figure it out yourself. Psychoanalysis helped the moderns to make sense of this question, and to try to arrive at an answer.

More than a century later, the situation looks different. If an earlier stage of capitalism laid the material foundations for a new experience of individuality, the present stage seems to be producing the opposite. In their taverns, theatres, and dance halls, the city dwellers of the Second Industrial Revolution created a culture of social and sexual experimentation. Today’s young people are lonely and sexless. At least part of the reason is the permanent connectivity that, as Pressly argues, conveys the feeling that “one’s time and attention—that is to say, one’s life—are not entirely one’s own.”

The modernist city promised anonymity, reinvention. The Internet is devoid of such pleasures. It is more like a village: a place where your identity is fixed. Online, we are the sum of what we have searched, clicked, liked, and bought. But there are futures beyond those predicted through statistical extrapolations from the present. In fact, the past is filled with the arrival of such futures: those blind corners when no amount of information could tell you what was coming. History has a habit of humbling its participants. Somewhere in its strange rhythms sits the lifelong work of making a life of one’s own. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com