Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your inbox.

If a dance isn’t performed for a long time, it starts to disappear. People’s memories of it fade, and videos can be confusing—choreographers’ notes, even more so. In short, reconstructing old dances isn’t easy. On the other hand, that process of rebuilding is inherently interesting. This is what the Paul Taylor Dance Company has been up to for the past few months, as it revives two Taylor pieces from the nineteen-sixties, “Tablet” (1960) and “Churchyard” (1969), for its weeklong run at the Joyce (June 17-22). “It took us two hours of research for every minute of dance,” Michael Novak, the company’s first leader since Taylor’s death in 2018, said recently. “But, eventually, we figured it out.”

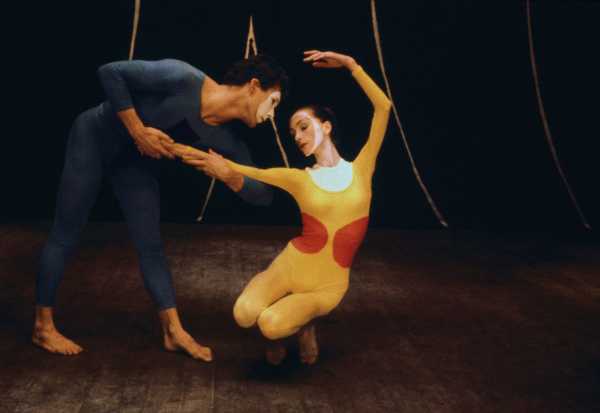

Pina Bausch and Dan Wagoner in Paul Taylor’s “Tablet,” in 1960.Photograph by Helga Gilbert; courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

For the company, it’s an opportunity as well. The current dancers work with those from a previous era; they get to perform Taylor works that, though old, feel new, and the audience get to see a work that they haven’t already seen many times before. It’s a clean slate. Plus, these particular dances are full of curiosities. “Tablet” is a duet with a commedia-dell’arte feel. The dancers wear face paint and color-block unitards, designed by Ellsworth Kelly. They bend and twist, creating geometries with their bodies. Sometimes, as they touch dispassionately, they look like a Cubist Adam and Eve.

“Churchyard,” a more complex piece, is one of Taylor’s explorations of false piety and the violence and grotesquerie that lie beneath. The setting is medieval—Taylor loved a period piece. It, too, contains a beautiful pas de deux. A man and a woman touch tenderly, creating an image of innocent love; then, suddenly, she kicks him. This juxtaposition of man’s contrasting natures is an important through line in Taylor’s work. “Churchyard” will be echoed at the Joyce by a more familiar work, “Cloven Kingdom,” from 1976, in which apparently polite men and women in formal attire devolve into strange, threatening behaviors. Then, there is “Esplanade,” set to Bach. Turning fifty this year, it’s perhaps Taylor’s sunniest, most welcoming dance and certainly one of his most beloved. These days, it looks almost classical. What is new? What is old? “I’m obsessed with the notion of what’s timeless and timely,” says Novak. “When I go back into the vault of Paul Taylor’s repertoire, I’m amazed at how avant-garde some of the work is.”—Marina Harss

About Town

Off Broadway

Aishah Rahman’s colorism dream-play “Chiaroscuro,” directed for the National Black Theatre by abigail jean-baptiste, drifts between states: reality and surreality, droll satire and sincere despair. Passengers board the mysterious S.S. Chiaroscuro for a “Chocolate Singles” cruise, only to find the sole crew member—the trickster Paul Paul Legba (Paige Gilbert)—more interested in divesting the Black couples of their obsession with light skin than in returning them to port. In the second hour, the show loses its sense of direction, but several strong performances still anchor the production: Gayle Samuels and Lance Coadie Williams bicker as exes who miss their second chance, and the forceful (and then heartbreaking) Ebony Marshall-Oliver plays a woman so tired of whitening her skin that she peels it right off.—Helen Shaw (National Black Theatre at the Flea; through June 22.)

TV

In the Prime series “Overcompensating,” Benny—played by Benito Skinner, the show’s creator—checks a near-comical number of boxes: valedictorian, football player, homecoming king. He is also a closeted gay guy who craves the acceptance of straight dudes, and the show is about the immense temptation to keep up such an act, even as the lack of authenticity becomes corrosive. Skinner is a particularly sharp satirist of the relentless policing of masculinity by other men. The pressure to conform to traditional masculinity isn’t new terrain—but the canon of queer television is still slim enough that “Overcompensating” feels fresh. Though Benny and his crush, Miles (Rish Shah), make eyes at each other, Benny’s friendship with his ostensible love interest, Carmen (Wally Baram), emerges as the real love story.—Inkoo Kang

Off Broadway

Jennifer Smith as Stage Manager.Photograph by Hollis King

“Prosperous Fools,” adapted by the protean queer theatre-maker Taylor Mac from Molière’s “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme,” turns the tension between making art and making money into an occasion for lampooning all involved, from artists and arts organizations to their mega-wealthy funders. A ballet choreographer who worries he’s a sellout (Mac, in a semi-autobiographical role) is presenting his work at a gala honoring a rich scumbag (Jason O’Connell) and a bleeding-heart philanthropist (Sierra Boggess, who somehow charms you with her character’s insufferableness). The show’s direction, by Darko Tresnjak, matches the zaniness of the script; what keeps the wild ride from going off the rails is the earnestness underlying Mac’s satire, which turns a shrewd eye on the corrupting potential of money in the arts, as anywhere else.—Dan Stahl (Polonsky Shakespeare Center; through June 29.)

For more: From 2019, a report on Mac’s sequel to Shakespeare’s “Titus Andronicus,” a play that reminded Mac of “Trump’s crudely menacing and unwittingly self-lampooning use of comedy, which, Mac added, ‘isn’t that funny.’ ”

Art

In the art collective Open Group’s video installation “Repeat After Me II” (2022, 2024), refugees from the war in Ukraine imitate the sounds of Russian weapons that haunt them—a striking woman with red lipstick and deep bags under her eyes vocalizes the “ssssssssssssss tuhfff tuhfff tuhfff”s of aerial bombs that nearly killed her family. The project represented Poland at last year’s Venice Biennale, and there, as here, the videos play in a military bunker-cum-karaoke bar with red lighting, crates of bottled water, and microphones. Each speaker ends by saying “Repeat after me”—a phrase that’s equal parts education and exhortation to stand at a mike and make the noises yourself. You may feel awkward, but that’s the point: doing so turns the witnessing of trauma into something inescapably visceral.—Jillian Steinhauer (601Artspace; through June 22.)

Folk Rock

Photograph by Jake Edwards

In the sixty years since he débuted with Art Garfunkel, the singer-songwriter Paul Simon has shaped an undeniable career around an ambivalent perspective. As half of Simon & Garfunkel and as a soloist, he has contributed significantly to American music. From “The Sounds of Silence” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water” to “Graceland” and “You’re the One,” his storytelling is nuanced, moving through an uncertain world with ease. Simon’s most recent album, “Seven Psalms,” from 2023, an acoustic song cycle, feels purposefully built for his “Quiet Celebration” tour, intimate live shows in venues selected for their sound properties. But even amid the quiet he will always find space for the classics.—Sheldon Pearce (Beacon Theatre; select dates June 16-23.)

For more: “You have to be vulnerable,” Simon told our reporter in 1967. “Every time you drop a defense, you feel so much lighter.”

Movies

The Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh, whose films have long borne witness to the country’s murderous Khmer Rouge regime of the nineteen-seventies (from which he escaped), returns with the drama “Meeting with Pol Pot,” based on a nonfiction book by Elizabeth Becker. It stars Irène Jacob, Grégoire Colin, and Cyril Gueï as French journalists who, in 1978, rely on political connections to interview the titular dictator. One reporter, a Marxist, plans to ask tough questions sympathetically; another is openly skeptical of the regime; and a third brazenly plans to leave his minders behind. The results, naturally, are tragic; Panh combines sharply observed action with archival footage and diorama-like re-creations—complete with clay figurines—of horrors that went undepicted.—Richard Brody (Film at Lincoln Center.)

Pick Three

For Jane Austen’s 250th birthday year, Alexandra Schwartz shares her favorite movie adaptations.

Photograph from Cinematic / Alamy

1. Political subtext made text. In Patricia Rozema’s “Mansfield Park,” from 1999, Frances O’Connor is wonderful as Fanny Price, the poor heroine sent to live with rich, careless relations. Harold Pinter plays Fanny’s uncle, whose fortune stems from Antigua. What is a hint in the novel becomes a horror onscreen when Fanny discovers sketchbooks showing sadistic scenes of plantation life. We often overlook the brutal basis of the social system that Austen analyzed so pleasurably; this is a potent reminder.

2. As if! As entertainment, Amy Heckerling’s 1995 classic “Clueless” is unsurpassable. As a reading of “Emma,” Austen’s prickliest novel, it is surprisingly profound. Transposing the gossipy life of the village of Highbury on to a Los Angeles high school at the turn of the millennium was a stroke of brilliance; it’s hard to think of two milieus where status, wealth, and romance matter more. Like Emma Woodhouse, Cher Horowitz is a totally unrelatable protagonist whom we can’t help but root for anyway.

3. Romantic, with a capital “R.” Joe Wright’s “Pride & Prejudice,” from 2005, stars Keira Knightley and Matthew Macfadyen as the two halves of English literature’s most famous couple. The movie’s tone can seem more Brontë than Austen: when Lizzy first turns Darcy down, it is in the middle of an epic rainstorm. That’s fine with me. Austen’s archness mixed with a Romantic emotionalism is as addictive a formula as salted-caramel popcorn.

On and Off the Avenue

Oh Là Là Department

Once or twice a year, when I’m feeling blue, I navigate over to YouTube to watch an incredible “60 Minutes” segment, from 1976, called “Bloomies,” about the Upper East Side department store Bloomingdale’s during its trendiest era. Back then, Bloomingdale’s was the spot to spend a Saturday; people went in droves, not necessarily to buy things but to see things (and to be seen by other people seeing things). It was less a sensible-goods emporium than a multi-sensorial playground. (The store did not sell refrigerators, for instance, but it did sell ceremonial masks from New Guinea and a four-hundred-and-fifty-dollar children’s bed in the shape of a tennis shoe.) My favorite part of the segment is an interview with the fashion writer and self-proclaimed Bloomies addict Blair Sabol, who gushes, “You have everything under one roof. You’ve got stockings, brassieres, tickets, brie cheese,” adding, “They know what’s in. They’re telling us, This is it, folks—get hip to the trip!”

Illustration by Rose Wong

I thought about Sabol’s words recently, as I walked into Printemps, a fifty-five-thousand-square-foot, dual-level, highly ornate shopping destination that opened in mid-March at 1 Wall Street. The store, an import from Paris (the first New York outpost of the popular French chain), taps into the esoteric energy of Bloomies’ heyday; it is the most beautiful, and least practical, department store to open in Manhattan in decades. Printemps, whose lush, whimsical interiors are the work of the Parisian designer Laura Gonzalez—the layout is purposefully meandering, following undulating curves and weird zigzags—bills itself as a “luxury retail experience.” This essentially means that it wants shoppers to do more there than simply shop: it wants them to wander, to gaze, to swan around, to rifle through diaphanous garments (the inventory leans toward French brands, like Lemaire and Courrèges), to primp in front of its offbeat, wavy mirrors, to sniff perfumes in its cave-like “beauty corridor,” to visit the spa for a facial, to pause for a cocktail (the store boasts four different bars, in addition to a roving champagne cart), to pause for a canapé (the in-house restaurant, Maison Passerelle, is run by the “Top Chef” alumnus Gregory Gourdet), and, generally, to linger. There are also mini-stores nesting within the big one—a “Petit Bazar,” displaying eclectic objets (artisanal crayons, novelty pillows, fancy tarot cards), and, as of this week, a boutique wine shop.

The jewel of the space is the Red Room, which features grandly restored crimson mosaic walls, by the artist Hildreth Meière, dating back to 1931, when the building was a bank. Now the room, decorated with giant lamps resembling drooping wildflowers, is a temple to a different kind of currency: designer stilettos (from the likes of Manolo Blahnik and Jacquemus). New York is ever changing, but some things are eternal: there will always be a shiny new palace of consumerism telling us, “This is it, folks.”—Rachel Syme

This Week With: Amanda Petrusich

Our writers on their current obsessions.

This week, I loved: the Los Angeles-based music critic Jeff Weiss’s first book, “Waiting for Britney Spears: A True Story, Allegedly,” a gonzo descent into the thrashing tabloid mania that has surrounded Spears for much of her career. It’s masterfully written and also completely bonkers—language that could also be used to describe several of Spears’s biggest hit singles.

This week, I’m stuck on: “Dollar Store,” a single from Ben Kweller’s heavy and excellent new record, “Cover the Mirrors.” This is Kweller’s first new album since his sixteen-year-old son, Dorian, was killed in a car accident two years ago, and the song is suffused with grief, though not in a particularly explicit way. It’s there in the crash and squeeze of the guitars, the arched claustrophobia of the vocals. It’s eulogy and catharsis, sorrow and reluctant acceptance, and it is gorgeous.

This week, I cringed at: the actress Sydney Sweeney making bars of soap containing “a touch” of her actual bathwater, for a collaboration with Dr. Squatch, a company that makes personal-care products marketed to men. Mostly, I recoiled at the description of the soap’s scent: “Morning Wood.”

This week, I’m consuming: Alison Roman’s lemon-roasted chicken with Tokyo turnips and green garlic. I made it terrifyingly far into adulthood without being exactly, uh, competent in the kitchen; the ability to roast a chicken always felt, to me, like the pinnacle of elegance and sophistication, and I’ve taken it upon myself to learn. Roman is my kind of Virgil—chatty, funny, forgiving, sharp.

Next week, I’m looking forward to: obsessively monitoring the auction of the David Lynch Collection, an assortment of the director’s personal effects, including two taxidermied deer heads, a 16-mm. film camera, prop menus from “Mulholland Drive,” a bakelite desk telephone he used while making “Dune,” ten copies of “Eraserhead” on VHS, four rustic log stools (very sick), an industrial shop vacuum, “nine neckties and a pair of glasses,” and various coffee-making accoutrements. (These feel like the most intimate and beloved objects in the collection—Lynch once said he drank twenty cups of coffee a day.) I’m an aesthetically charged person who believes in the weird gravitational pull of objects; it’s a melancholic thrill to get a closer look at some of the items that populated Lynch’s world. His work meant a lot to me, and, now that I’ve seen them, his mugs do, too.

P.S. Good stuff on the internet:

- On finding mystery in the digital age

- Watching boulders wander

- Pirates of the ayahuasca

Sourse: newyorker.com