Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Charles Frederick Worth, the nineteenth-century designer widely credited as the inventor of haute couture, was not a modest man. “Madame, on whose recommendation have you come to me?” he is said to have asked a prospective client at his Paris salon, a woman ready to pay the exorbitant fees generally required for his services. “If you wish to be dressed by me, you must have an introduction,” he explained. “I am an artist of the stature of Delacroix.”

Worth had good reason to be confident. His most important client, during a fifty-year career, was an empress, but tsarinas, society mavens, actresses, and courtesans all came to rely on his expertise. His “upholstery-style” gowns, laden with draperies, ruffles, embroideries, and fringe, illustrated to a rare degree the sociologist Thorstein Veblen’s concept of “conspicuous consumption.” At a time when a married woman’s ability to own property was severely restricted, a Worth dress signalled that its wearer was related—by blood, marriage, or the lust she was capable of inspiring—to at least one grand fortune. This was no small thing in a rapidly changing society, in which wealth, concentrated in the hands of the few, could be made or lost overnight.

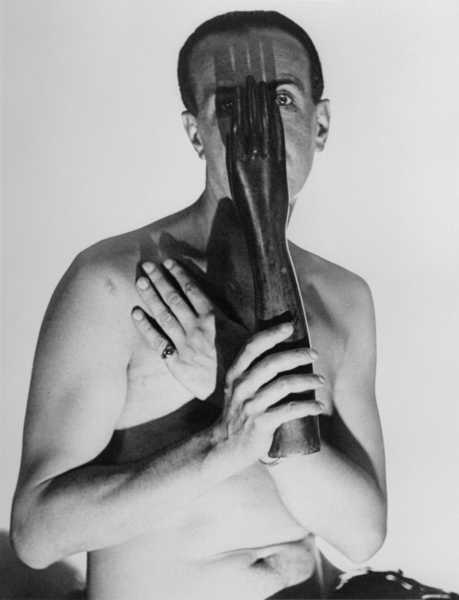

Now visitors from our own rapacious era can cross Paris’s exuberantly gilded Pont Alexandre III (itself a product of the Belle Époque) and enter the airy halls of the circa-1900 Petit Palais, where “Worth, Inventing Haute Couture” will be on view through September 7th. Organized in collaboration with the Palais Galliera, the show features more than four hundred rarely exhibited works. Clothing, paintings, photographs, and objets d’art trace the House of Worth’s history from its founding, by Charles Frederick, during the age of crinolines, through its second flowering in the Edwardian era, when his sons Jean-Philippe and Gaston assumed control, and on to the nineteen-twenties and thirties, when his grandson Jean-Charles ushered Worth’s lavish style into the Jazz Age while launching perfumes, befriending artists, and posing naked in a series of photographs by Man Ray. Along the way, the show argues, the house set the template for many of the conventions and myths that still govern the creation of high fashion today.

Photograph of Jean-Charles Worth, 1925.Photograph by Man Ray / Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, Paris / Image Telimage, Paris

“Opulence, theatricality, and historicism” were the hallmarks of Worth’s style, the fashion historian Sophie Grossiord, who co-curated the exhibition with Marine Kisiel and Raphaële Martin-Pigalle, explained one morning at the Petit Palais. She was standing next to a day jacket with a nipped-in waist, high neck, and puffed sleeves, made of midnight-blue velvet and appliquéd with arabesques of pale-violet satin. (On its wide Renaissance-style collar, the design is reversed: the arabesques are blue, the ground violet.)

This marvellous jacket was something that Renée, the tragically spendthrift heroine of Émile Zola’s novel “The Kill,” might have loved. Enmeshed one Parisian winter in a reckless affair with her stepson, Renée orders from her couturier, Worms, “a complete Polish suit . . . in velvet and fur” to go ice-skating with her young lover in the Bois de Boulogne. Zola conducted extensive research at the House of Worth for his portrait of Worms as a temperamental artist, servicing a society ruled by capital and addicted to luxury. Renée spends hours at the salon of “the couturier of genius to whom the great ladies of the Second Empire bowed down,” waiting alongside “a queue of at least twenty women.” When at last she stands before him, holding her breath, he “pondered with knit brows” before sketching an outfit for her while exclaiming in short phrases, “a Montespan dress in pale-grey faille . . . puffed apron of pearl-grey tulle.” Much of the novel is devoted to the ruthless scheming of Renée’s husband, Saccard, a property speculator intent on profiting from the vast geographical changes afoot in Haussman’s Paris. But Zola devotes his novel’s last words, after Renée’s sudden death, to a bill from Worms.

A Worth tea gown or robe d’intérieur worn by Countess Greffulhe, circa 1896-1897.Photograph by Stanislas Wolff / Palais Galliera, Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris

No mere dressmaker, Worth was the first designer who regularly imposed his own ideas on clients—telling a woman who wanted a blue dress that pink would suit her better, say. He was known for his ability to create gowns and costumes at tremendous speed; in a pinch, these could be sewn directly onto clients, with his last-minute adjustments. On the evening of a ball, for example, a crush of ladies would wait in line inside the house’s legendary address at 7 Rue de la Paix. They were each “given a ticket,” Diana de Marly, author of the 1980 biography “Worth: Father of Haute Couture,” recounts, “and served with Malmsey Madeira and pâté de foie.” (I also read these details in “The House of Worth, 1858-1954: The Birth of Haute Couture”—published in 2017 and co-authored by Charles Frederick’s great-great-granddaughter, Chantal Trubert-Tollu.)

Gazing at the results of his ministrations—bejewelled, fin-de-siécle fantasies of valkyries, infantas, Zenobias, and their ilk, arrayed on a row of mannequins at the Petit Palais—I found myself wondering what drove the members of European society to dress up as divinities or royal personages. Were they attempting to shore up an authority buffeted by repeated political reversals? In fact, there was considerable overlap between Worth’s costumes and the garments intended for his élite clients’ everyday lives, since their participation in society required them to appear continually “on parade.” Wealthy Americans, meanwhile, some flush with robber-baron fortunes, flocked to the house to acquire the sheen of aristocracy by association.

In a recent episode of HBO’s “The Gilded Age,” Bertha Russell (Carrie Coon), the nouveau-riche wife of an American railroad tycoon, explains to her less cosmopolitan sister that her life often involves three to five changes of outfit per day. The exhibition offers up for our delectation silk taffeta robes à transformation, their wide skirts equipped with interchangeable bodices (sober and long-sleeved for daytime, daringly décolleté for evening); tea gowns with enormous gigot sleeves and lace yokes, for afternoons spent receiving friends at home; velvet cloaks, beribboned and befurred, for nights at the opera; and ethereal wrappers adorned with pale chiffon flowers, to cover the shoulders that a ball gown left bare.

“Une soirée” (1878), by Jean Béraud.Photograph by Hervé Lewandowski / RMN Grand Palais / Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Meanwhile, hanging nearby, Jean Béraud’s satirical 1878 canvas, “Une soirée”—a sendup of masculine concupiscence—shows such fashionable attire in action. In a teeming ballroom, a white-whiskered gentleman wearing a dinner jacket gazes avidly, if from a discreet distance, at the tightly cinched midriff (almost Kardashian-esque in its exaggeration) of a woman whose back is turned to him, though the train of her evening gown swishes enticingly in his direction. (The joke is on viewers, too, whose eyes are drawn to the wasp waist at the painting’s center.)

The curators reconstruct the haute-couture salons of the fabled Rue de la Paix through photographs, archival films, and displays of dresses by other designers. Paquin set up shop on the street alongside Worth, Doucet, and other luxury purveyors, and, by 1899, the jeweller Cartier had also moved there. (The Worth and Cartier dynasties intermarried twice—unions made in a deluxe heaven.)

In 1901, Charles Frederick’s son Gaston hired the young designer Paul Poiret, tasking him with adapting the house’s style to a world in which some princesses, at least, were beginning to take buses or go about on foot. But Poiret’s avant-garde ideas—evident in the kimono-inspired cut of a Révérend coat on view—horrified Worth’s more conservative clientele. (At the Petit Palais, you can put on headphones to hear the Russian Princess Bariatinskaya, a frequent client, railing against it.) Poiret, nonplussed, moved on just two years later to found his own couture house. Yet, within a short time, styles at the House of Worth evolved in his direction.

Finally, in a gallery devoted to the workrooms that occupied the upper floors at 7 Rue de la Paix, there are nods to the house models and seamstresses on whose ceaseless toil all this extravagance rested. In one vitrine, a humble black iron keeps company beside a little metal box for holding pins or thread. The box, painted with a picture of two kittens and said to have been given by Charles Frederick to Annette Sieutat, the head seamstress of his atelier for daywear, suggests a life passed in demanding, patient service to an elusive ideal.

The man at the center of this maelstrom of feminine splendor, Charles Frederick Worth, was born in 1825 in Lincolnshire, England, the youngest of five children of a solicitor father who squandered the family fortunes, and a mother compelled by straitened circumstances to work as a governess for wealthy relatives.

As a young boy, Charles was apprenticed to a printer in Bourne. A lawyer passing through town got him a job at a department store in London, where, in his spare hours, he haunted the Royal Academy of Arts to look at paintings. Paris, that capital of fashion, soon beckoned. Moving there in the mid-eighteen-forties, he made a name for himself at a high-end draper’s shop, Gagelin-Opigez, where he sold silks and shawls and oversaw the “confection” of semi-ready-made dresses as they were adapted for individual clients.

In 1851, he married Marie-Augustine Vernet, who became his assistant and an effective live model for the outfits he began creating. The following year, after a coup d’état, Napoleon III, the nephew of Napoleon I, became Emperor of France, and republican Paris was quickly transformed into the capital of consumption for an imperial society.

In 1858, with the financial backing of a Swedish partner, Otto Gustav Bobergh, Worth & Bobergh set up shop on the Rue de la Paix. Princess von Metternich, the fashionable wife of the Austrian ambassador, was the first to wear one of their dresses at court—a fluffy creation in white tulle, spangled with silver and embroidered daisies, with a wide white satin sash that she studded with diamonds. Her outfit caught the eye of Empress Eugénie, who became a faithful client, frequently commanding Worth to attend her in her apartments at the Tuileries. Ignoring protocol, he’d appear there in the artistic uniform that he wore at all his fittings, a late version of which is visible in a photograph Nadar took of him in 1892. In that photo, he styled himself after a Rembrandt self-portrait in a fur-trimmed cloak worn over a painter’s suit with a floppy necktie, and a beret that covered his baldness.

Charles Frederick Worth, 1892.Photograph by Nadar / Librairie Diktats

His extravagant designs were the perfect fit for an era of increasing ostentation; the constant references in his work to historical modes of dress suited a society ruled by a cipher, Napoleon III, whose power derived from his association with his famous uncle. Couture, Worth would find, even had a role to play in diplomacy, as when he helped the emperor broker an agreement with the restive silk manufacturers of Lyon, by encouraging Eugénie to wear a gown made of their fabrics. But greater challenges lay ahead. The Empire fell in 1870, a casualty of its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. (Worth, ever the showman, allegedly escaped a Paris under siege by hot-air balloon.) The Paris Commune—seventy-two days of intense revolutionary fervor—followed.

Still, society’s craving for opulence, though never again as acute as under the Second Empire, proved surprisingly durable. Less than eight months after the Commune’s bloody repression, the novelist and shrewd social chronicler Edmond de Goncourt would note in his diary the return of a traffic jam of fashionable carriages outside 7 Rue de la Paix.

By then, Worth’s partnership with Bobergh had dissolved, yet astronomical prices remained part of his work’s allure. He estimated at the time that a middle-class Parisienne’s entire yearly budget for clothing—roughly fifteen hundred francs d’or—would be enough to purchase just a single one of his day dresses, and the simplest one, at that. From the 1880s onward, his gowns bore his signature on their labels, like the works of an artist. Taken from his passport, that signature would carry his name to far-flung seats of power in British India and imperial Russia and Japan.

His technical innovations in the realm of fashion were limited. In the mid-1860s, he helped bring about the decline of the crinoline (a fire hazard when women in wide dresses brushed past flaming hearths). A few years later, he encouraged still slimmer dresses featuring flat-fronted skirts with excess drapery drawn toward bustles in the back. He introduced the idea (prevalent today) of seasonal collections, preparing spring-and-summer models, for example, to be shown in January. His “princess line,” first designed for an actual princess, Alexandra of Wales, dispensed with the traditional seam at the waist joining bodice to skirt, replacing it instead with panels that further elongated the figure.

The princess line reached its apogee around the turn of the century, in the creations of Jean-Philippe for the House of Worth’s most exacting and original client, Élisabeth de Riquet de Caraman-Chimay, a.k.a. the Countess Greffulhe. This unhappily married aristocrat ran an illustrious salon and patronized the avant-garde in music and science, though today she is chiefly remembered as the model for the fictional Duchess of Guermantes, a distant object of longing for the child narrator in Marcel Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time.”

Yet the countess’s greatest achievements may have resided in the ephemeral realm of fashion. The vivid splendors of her wardrobe, designed in collaboration with the House of Worth and on display at the Petit Palais, include a sumptuously patterned emerald-green satin and blue cut-velvet tea gown and a high-necked silver lamé dress, embroidered with a Byzantine profusion of gold thread, sequins, and artificial pearls, in which she outshone her own daughter on her wedding day. I was most taken with the Bukharan man’s embroidered cloak—a gift to her from the last tsar, Nicholas II—which she commissioned Jean-Philippe to transform into an evening mantle, unique and fit for a queen. “She cares about fashion, but not to follow it,” the countess once noted of her ideal.

“Winning in business and winning in society are linked,” Bertha Russell, intent on clawing her way up the social ladder of turn-of-the-century New York, tells her husband, George, on “The Gilded Age,” spelling out the stakes of their daughter’s potential failure to marry a weaselly British duke. Bertha wears a negligée in this bedtime scene, but at the height of her social triumph in the finale of Season Two, during the Metropolitan Opera’s inaugural opening night, she is dressed in a pale-blue gown with a teal scrollwork pattern reminiscent of Art Nouveau ironwork, and modelled on a similar gown by Worth.

An installation view of “Worth, Inventing Haute Couture” at Petit Palais.Courtesy Paris Musées / Petit Palais, musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris / Gautier Deblonde

Early in the twentieth century, Coco Chanel’s minimalist chic appeared to sweep Worth’s style into the dustbin of history; yet Christian Dior’s postwar New Look revived Belle Époque fashions, and subsequent heirs to Worth include designers such as Charles James, Vivienne Westwood, Christian Lacroix, John Galliano, Alexander McQueen, Sarah Burton, and Jean-Paul Gaultier. Today, we can see a nod to Worth’s style in a tightly corseted, heavily embroidered, more-is-more look worn by Lauren Sanchez in the run-up to her wedding with Jeff Bezos. The dress in question was by Daniel Roseberry for Schiaparelli Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2025. In a recent interview, Roseberry cited Worth as an inspiration.

“I’m so tired of everyone constantly equating modernity with simplicity,” he told 10 Magazine. “Can’t the new also be worked, be baroque, be extravagant? Has our fixation on what looks or feels modern become a limitation? Has it cost us our imagination?” Worth, a couturier of high-flown fantasies, would probably call that too high a price. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com