Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

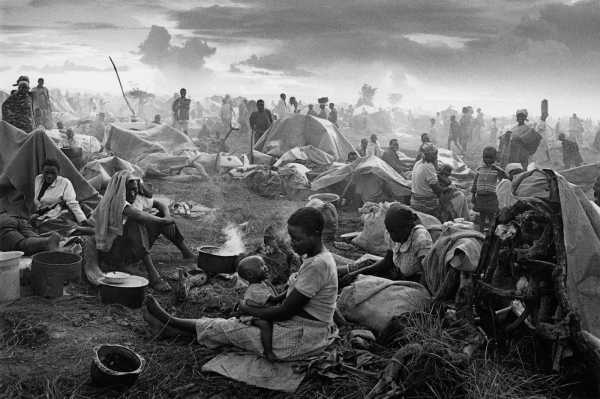

Sebastião Salgado, who died last week, of leukemia, at the age of eighty-one, was among the most famous documentary photographers of the twentieth century. Throughout more than four decades of epic, globe-spanning projects, many of which were both self-assigned and largely self-funded, he forged an instantly recognizable aesthetic in a field that tends to shy away from overt authorial touch. His pictures were sweepingly cinematic, symbolically loaded, and unabashedly gorgeous, even when he was photographing some of the greatest human horrors of the past century, such as the famine in the Sahel region of Africa in the mid-nineteen-eighties, or the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. A latter-day cornerstone of what Cornell Capa once dubbed “concerned photography,” Salgado’s work earned him numerous prestigious prizes and was showcased in grand touring exhibitions and in hefty coffee-table books. Sandra Phillips, the former senior curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, once called him “one of the most important artists in the Western Hemisphere.”

Rwanda Refugee Camp, 1994.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Salgado’s pictures were also freighted with their fair share of controversy. Susan Sontag, in her final book, “Regarding the Pain of Others,” called him “a photographer who specializes in world misery,” whose work “has been the principal target of the new campaign against the inauthenticity of the beautiful.” The critic and editor Ingrid Sischy wrote in a scathing 1991 piece for The New Yorker that Salgado’s work was “oversimplified,” “heavy-handed,” and ultimately ineffectual. “To aestheticize tragedy,” she said, “is the fastest way to anesthetize the feelings of those who are witnessing it. Beauty is a call to admiration, not to action.” How you feel about Salgado’s work might depend on whether you agree with that statement. If you believe that difficult truths should be delivered only in their rawest, plainest form (which is, of course, simply another form of artifice), then Salgado’s stunning images are not for you. But, if you believe, as I do, that most viewers are savvy enough to separate content from form, then Salgado’s operatic style can be seen as a potent enhancement of his act of bearing witness.

Refugees in the Korem Camp, Ethiopia, 1984.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Salgado was born in the Brazilian municipality of Aimorés, in the state of Minas Gerais, in 1944. He grew up on a cattle ranch alongside seven sisters, and as a young man he became an avowed Marxist. After a military coup in 1964, he and his wife, Lélia, fled to Paris, where he completed coursework for a Ph.D. in economics from the Sorbonne, before taking a job in London at the International Coffee Organization. He stumbled into photography after borrowing a camera Lélia had purchased to aid in her studies to become an architect, and became so quickly enamored that, soon enough, he built a darkroom in their apartment. After some debate, he turned down a job offer with the World Bank and resolved to become a photographer.

First Communion in Juazeiro do Norte, Brazil, 1981.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

Within a few years of working as a peripatetic photojournalist, during which he covered a handful of minor conflicts and standard-issue fare such as golf tournaments, Salgado secured a spot with the legendary photo agency Magnum, in 1979. (He later broke with Magnum to found his own agency with Lélia, Amazonas Images, which exclusively represented his work.) In 1981, on assignment covering the early days of the first Reagan Administration, he took a career-making series of pictures of the aftermath of John Hinckley, Jr.,’s assassination attempt, which were picked up by newspapers across the globe—and the financial windfall from these shots allowed him to purchase the Paris apartment that he lived in with his wife until his death. But Salgado undertook his most ambitious projects independently.

Eastern Part of the Brooks Range, Alaska, 2009.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

Gold mine, Serra Pelada, Brazil, 1986.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

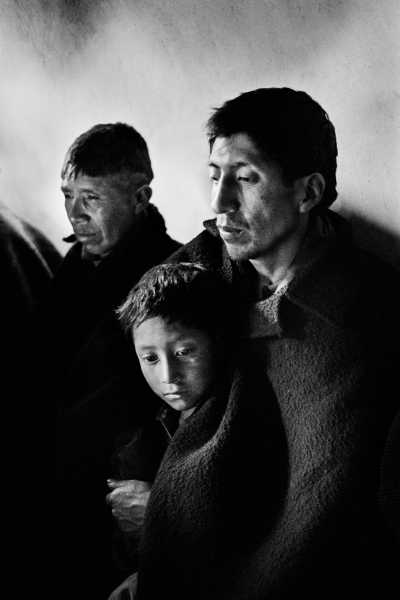

“Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age,” the first of three mammoth series completed over nearly three decades, was an attempt to commemorate manual labor at a time of rapid mechanization. The pictures, which were taken in twenty-six countries, cover an exotic range of human endeavors, including the production of perfume in Réunion, the quelling of the Kuwaiti oil fires, and, most famously, the toils of gold miners in Serra Pelada, Brazil. Overwhelmingly, the pictures portrayed manual work as a noble, even romantic enterprise. In one, we see a Galician fisherman perched at the head of a small, crowded boat, staring into the middle distance with a gravity befitting Odysseus. In another, we see a Bangladeshi ship-breaker dwarfed by the sublimely towering husk of a boat docked on a beach, suggesting an industrial-era update of Caspar David Friedrich’s “The Monk by the Sea.”

Fishing in the Piulaga Laguna during the Kuarup ceremony of the Waura Group. Upper Xingu Basin, Mato Grosso, Brazil, 2005.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Sischy, in her critique of Salgado, wrote that his approach to industrial labor shared none of the activist bite of Lewis Hine’s turn-of-the-century pictures of child laborers, which famously played a role in cementing anti-child-labor legislation. Salgado’s “basically uncritical” pictures, Sischy asserted, “would look at home in corporate annual reports.” Like Hine in the latter part of his career, which was largely defined by his heroic, semi-staged photographs of workers, Salgado was principally concerned with portraying the fundamental humanity of his subjects, asserting the value of their work rather than portraying them simply as victims of rapacious exploitation. In this way, they were perhaps closer to Soviet-style socialist realism than they were to boosterish corporate pablum.

Gold Mine, Serra Pelada, Brazil, 1986.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

A worker rests after an exhausting day trying to put new heads on the wells. Workers toil in twelve-hour shifts. Kuwait, 1991.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

Last year, on the occasion of Taschen’s reissue of “Workers” (originally published in 1993), I had the chance to interview Salgado over video chat. He was in Paris, sitting in his studio, with a mural-size print of one of his photographs behind him. Salgado had a smooth shaved head and wild white eyebrows. In conversation, he was charming and genial, but he is well practiced in sparring with his critics. “People criticize me that what I do is the beauty of the misery,” Salgado told me. “But I never, I never, photograph the misery. Never. I photograph people that were less rich in material goods. Misery, what is the misery?” His follow-up to “Workers” was a project called “Exodus,” which documented the world’s deracinated people—migrants, exiles, refugees. He spoke to me of the importance of community. “When I photograph the refugees that come out of Malawi, going inside Mozambique—if one of them dies, the others will cry for him. You see they have not a bank account, they have no shoes. But they were proud. They were happy. They have a family that they live inside. And they deserve to have a nice picture. Why not?”

Wake, Village of Alao, Region of Chimborazo, Ecuador, 1998.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

After spending time in Rwandan refugee camps, Salgado told me, he suffered from a series of physical and mental maladies. He saw a doctor back in Paris who told him that, though there was nothing physically wrong, if he kept pursuing his work he would surely die. “I was so upset to be a human being,” he said, “because I saw the amount of violence that we are capable of. We are a terrible species. I gave up photography. I said, ‘Never more in my life I do pictures.’ ” Salgado put his camera away and moved with his wife back to Brazil, to the family cattle ranch, which he had inherited from his father. When they arrived, they found the land nearly denuded of life. Lélia suggested that they might try to rewild it, partly as a form of therapy and partly out of ecological concern. Decades later, what is now called the Instituto Terra is a lush Eden, replete with wildlife and more than two and a half million trees, and serves as a kind of laboratory, providing inspiration for similar projects around the world. “This forest coming back gave me a huge wish to photograph again,” Salgado told me. “And in this moment I said, ‘I go to see my planet.’ I wanted to see what is pristine in this world.”

Zo’e Group, State of Para, Brazil, 2009.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

The resulting eight-year project, “Genesis,” was a paean to natural landscapes and Indigenous ways of living, from Antarctica to the Amazon rain forest. The project is tinged with a tentative note of optimism—look how much of our Earth remains unspoiled—but it also represents a sort of pulling away from humanity. “Before then, I had only faith in humanity,” he told me. “I started to discover that the planet was not composed only of human beings.” Salgado, who is survived by Lélia, their two sons, and two grandchildren, was eighty years old at the time of our conversation. Although he was still occasionally making pictures—he had been trying his hand at drone photography—his days of crafting large-scale projects were over. The waning of Salgado’s career seemed to mark the end of an era of ambitious, essayistic photojournalism, which has been under pressure for more than a decade owing to dwindling print-publication budgets and increased reliance on iPhone-toting “citizen journalists.” Salgado reflected on the privilege of seeing the world as thoroughly as he had. “To see what I see, to have contact where I have—I lived really deep inside the human communities, and I lived deep inside the environment. If it was necessary to start again, I would start exactly as I did before. I had a big pleasure in my life.”

Pico da Neblina, Brazil, 2009.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Sourse: newyorker.com