Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In 2001, a friend of mine, the artist Daesha Devón Harris, attended the opening of a Renée Cox exhibition at the Robert Miller Gallery, in New York. At the time, Harris was an eager young photography student constantly looking for Black women to inspire her practice. She loved the Miller show, which featured photographs that had been printed in enormous proportions—some were seven feet high by four feet wide—and which played with historical and religious iconography to explore Black womanhood. As Harris, vibrating with gratitude, was preparing to leave, a sleek black BMW F 750 GS motorcycle rode directly into the gallery, a gray plume of smoke trailing behind it. A woman dressed in head-to-toe black leather turned off the engine and stepped onto the gallery floor, shaking loose her shoulder-length brown locs as she did so—that was Cox.

I love this anecdote, which conveys the style and fierceness of the Renée Cox I know and love. I first met Cox in 2019, after being introduced to her by a friend. At the time, I needed a gig, so I worked as her studio manager for about four weeks, organizing her hard drives and archives. During that time, I got to learn from her, and to know her as an unflinching, brazen, and uncompromising artist.

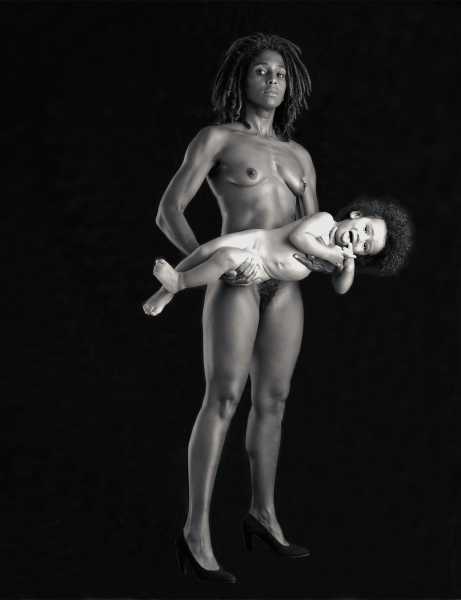

“The Yo Mama,” from the series “Yo Mama,” from the diptych “Origin,” 1993.

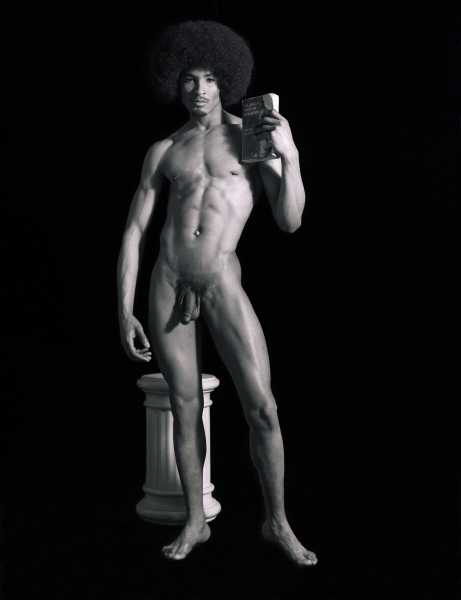

“David,” from the series “Flippin’ the Script,” from the diptych “Origin,” 1994.

For the past four decades, Cox, who was born in Jamaica and raised in the U.S., has been making photographs of Black women which cast them as complex protagonists. In a body of work that spans fine art and fashion photography, she has repurposed familiar imagery to broaden the scope of how we envision our deities and our histories. Many of her most powerful works are self-portraits. In “Yo Mama’s Pieta” (1994), Cox appears as a modern-day Virgin Mary, holding the beautiful, limp body of a nude Black man. “Black Panther Last Supper” (1993) features a cast of Black models, including herself, in place of the figures of da Vinci’s painting.

“Yo Mama’s Last Supper,” from the series “Yo Mama,” 1996.

Cox got her start young. As a high schooler, in Scarsdale, she was initially interested in filmmaking, but a clerical error placed her in a photography course instead. She fell in love with the medium and was a quick study, learning to print from her male classmates. (There were no other girls in her class.) When she arrived at Syracuse University, as a film major, she became disenchanted by the arduous process of editing her films. “Being a baby boomer, I was into immediate gratification,” she told me, laughing. Her interest in fashion photography began when she started photographing customers at local hair salons in the mornings, documenting their chic outfits and freshly styled hairdos.

After graduating in 1979, Cox strategized about how best to break into fashion photography. She landed on modelling. “In those days, it was a very male-oriented profession, so nobody was going to hire me as a photographer,” she said. Her first big job was for a Glamour spread photographed by Brigitte Lacombe, in which she played a girl who had just graduated from college and was looking for work in the big city. Her style and makeup skill so impressed the team that, at the end of the four-day shoot, she was hired as an assistant fashion editor at the magazine, a position that granted her access to clothes, test-shoot locations, and the chance to further develop her eye for beauty.

“Missy at Home,” from the series “The Discreet Charm of the Bougies,” 2008.

“Lost in Mongolia,” from the series “The Discreet Charm of the Bougies,” 2008.

In 1980, Cox got married, left her job at Glamour, and moved to Paris for two years. After her return to New York, she spent the rest of the eighties on beauty, fashion, and commercial work—she shot spreads for Cosmopolitan, Essence, and other magazines, along with the poster for Spike Lee’s “School Daze” and album covers for the Jungle Brothers and Gang Starr. But, as the decade dissolved, things began to shift. In 1989, she became pregnant, and started to consider her legacy. “I realized that the work I was making only had a twenty-eight-day life span, and then it was on to the next shoot. I felt like my photos were better than twenty-eight days, that they should have some sort of life on their own.”

“Young Yo Mama,” from the series “Yo Mama,” 1980.

In 1990, as a new mother, she began attending the School of Visual Arts, where the artist Lyle Ashton Harris, a friend, had encouraged her to enroll. She knew then that she wanted to make photographs that examined race, identity, and gender, and that she wanted to use her own body as the primary vehicle for that examination. Grad school gave her the time to solidify what she wanted to say with her art. After S.V.A., Cox attended the Whitney Museum’s prestigious Independent Study Program (I.S.P.), which allowed her concentrated time to sharpen her focus as a fine artist. The experience gave her a new scholarly rigor, as well as direct access to the art world, but it wasn’t without its problems. During her time there, she was pregnant with her second child, and people regularly made disparaging remarks to her. “At an opening once, someone said, ‘Back in my day, we’d cover that up,’ to which I responded, ‘If I was back home in Jamaica, I’d have on a bikini.’ ”

“Yo Mama at Home,” from the series “Yo Mama,” 1993.

The I.S.P. experience charged Cox’s practice with newfound clarity and discipline. She embarked on more conceptually complicated work, like her “Yo Mama” photographs, a series of self-portraits that meditate on motherhood and the body in ways both subtle and confrontational, and “Queen Nanny of the Maroons,” a series in which Cox casts herself as the legendary Queen Nanny, a Jamaican woman who led a revolt of the enslaved and who stands as a symbol of unity and revolution. One of my personal favorites is “Raje,” a series in which she appears as a superhero attempting to rescue Black people from racial stereotypes. In “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben” (1998), one of Cox’s best-known works, she and two other superhero figures lock arms in front of the notoriously exploited images of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, attempting to protect their visages from further misuse. Despite their campiness, the “Raje” images convey an important criticism of the history behind these two figures, while positing the need to see Black superheroes. Today, in an era when we have superheroes like Black Panther, and the companies formerly known as Uncle Ben’s and Aunt Jemima have officially changed their names, the photographs also establish that Cox has always been prescient.

“March,” from the series “Queen Nanny of the Maroons,” 2004.

“The Enlightenment,” from the series “The Discreet Charm of the Bougies,” 2013.

At sixty-three, Cox has not slowed down one bit. In the last two years, she has had a gallery show and three museum shows, the most recent of which is “Renee Cox: Revolution/Revelation,” at the Newport Art Museum, on view until October 6th. In her newer works, she continues to experiment with form. In “Soul Culture,” a series from 2016, she uses portraits of models, artists, and actors to assemble kaleidoscopic fractals, in a nod to ancient African mathematics. She has dabbled in N.F.T.s and created installations using projection mapping, a spatial-mapping technique that turns irregularly shaped surfaces into multidimensional screens to project images upon. She continues to make editorial photography, recently photographing a cover for the T, the Times’ style magazine, and is a long-standing photo critic at Yale. Though the new attention swirling around her work is heartening, it stupefies me that she still does not have gallery representation, and that no publisher has put out a retrospective monograph collecting and contextualizing the contributions of this boundary-breaking artist.

“doc twins,” from the series “Soul Culture,” 2018.

Sourse: newyorker.com