Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The photographer Luis Corzo was six years old when he was kidnapped. Early on the morning of April 18, 1996, armed members of a small gang forced their way into the garage of his family’s home, in Guatemala City. Corzo’s brother saw what was happening and ran back into the house. His sister was getting ready for school in another room. Corzo, who was the youngest of the three siblings, was standing in the garage. The kidnappers grabbed him. They were about to take his mother when his father offered himself up instead.

The third proof of life offered to Corzo’s family was left by the abductors on the back of this sign.

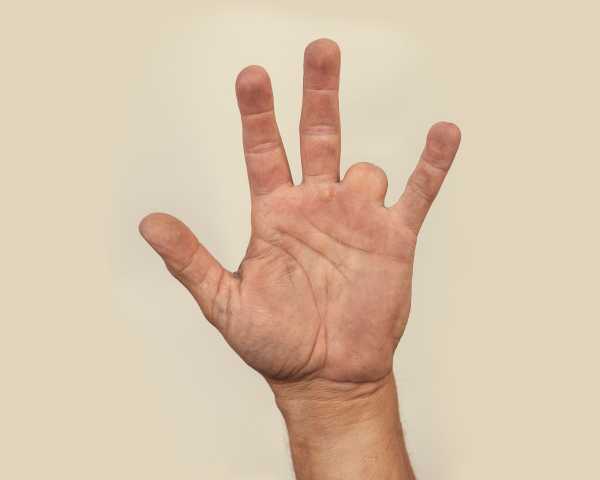

Corzo spent the next twenty-five years trying to reconstruct the month during which he and his father, Juan Corzo, Jr., were held for ransom. Fragmentary moments persisted in Luis’s memory: a Dominican merengue playing in the background at one of the stash houses, the shadow puppets that he and his father made with their hands to fill the empty hours. The other horrors were harder to remember in detail, even though they were far more haunting. Near the end of their captivity, the kidnappers cut off the ring finger of Juan’s left hand. They left it for the family in a plastic container in the bathroom of a fast-food restaurant as a threat to pay up.

A home in Pasaco, the municipality in Guatemala where the gang of Corzo’s kidnappers originated.

Juan was eventually released on May 18, 1996, but the kidnappers held Luis for three additional days, to extort more money from the family. For much of Luis Corzo’s childhood, his mother celebrated May 21st as though it were his birthday. She’d invite his friends over, serve cake, and hang a piñata. “I’d always be struck by attacks of trauma, and the parties would end badly,” Corzo told me recently. His own recollections of captivity were a jumble of sometimes untraceable sensations. “I don’t know if some of them were dreams or hallucinations,” he said.

Corzo’s mother, María Spillari.

Corzo’s grandfather Juan, Sr.

In 2011, as a photography student in Barcelona, Corzo began to research the kidnapping for his thesis. At home, the topic had assumed the protean quality of forbidden family lore. For the first time, he listened to the recording of a phone call that Juan had made to his family when he was released; at the time, they had gathered at Corzo’s grandfather’s house while negotiating payments with the kidnappers. “It broke me down,” Corzo said. “I couldn’t handle it.” He decided to abandon the project, but, in the process, he felt that he’d succeeded in exorcising some of the trauma.

Approximately nine days into the abduction, the Corzo family received a video of Luis and Juan Corzo, Jr., in captivity.

Eight years passed before he returned to the subject. By then, his approach to the incident had become more politically informed. He and his mother used to argue about whether the kidnappers deserved the death penalty. Five of them, including a leader of the gang, had been arrested and sentenced to death. Corzo’s parents had testified against them in court, a rarity in Guatemala at the time, and the family eventually had to leave the country for their own protection; Corzo grew up in the suburbs of Miami. His mother, who felt that the men might escape from Guatemala’s notoriously dysfunctional prison system, considered capital punishment the safest outcome. Corzo opposed it on principle.

Corzo and his father were first held in a stash house in Guatemala City.

“This had nothing to do with therapy or closure anymore,” he told me. “It was more that I had access to this story. I had access to a story that could serve a bigger and more important cause.” What interested him most was why his captors had resorted to kidnapping him and his father in the first place. “I am investigating this to be able to speak about the corruption in Guatemala that causes people to be stuck in total poverty and forces them to migrate, to rob, to kidnap,” he said.

The result of his reckoning is the book “Pasaco, 1996,” which was published in 2023. Its introduction, written by the investigative journalist Claudia Méndez Arriaza, begins with a quote from Claudia Paz y Paz, a pioneering attorney general from the twenty-tens, who’s since been forced into exile: “This country does not stand as tall as its victims.”

Corzo’s politics aren’t immediately evident in any of the photographs. The book is a kind of diary in which he combines archival images with new pictures of the places and people at the center of his story. The fact that they have all changed in the intervening years—and that we’re allowed to see the transformation—only underscores the force of Corzo’s obsession. You can almost feel him trying to make the past and the present cohere, though he’s hardly naïve enough to think they ever could.

A proof of life included a video of Corzo, blindfolded.

One of the book’s first images is a bare white church in Pasaco, a municipality of some nine thousand people near the border with El Salvador where the gang had originated. The simplicity of the structure, with its triangular façade and modest bell tower, suggests that Pasaco could stand in for so many other Guatemalan locales. In 1996, a civil war that had lasted more than three decades was finally coming to an end, but an epidemic of kidnappings was sweeping the country. Corzo’s grandfather, the family patriarch, had founded a paper-goods company. His financial success inadvertently turned the family into a target.

The kidnappers amputated the left ring finger of Corzo’s father.

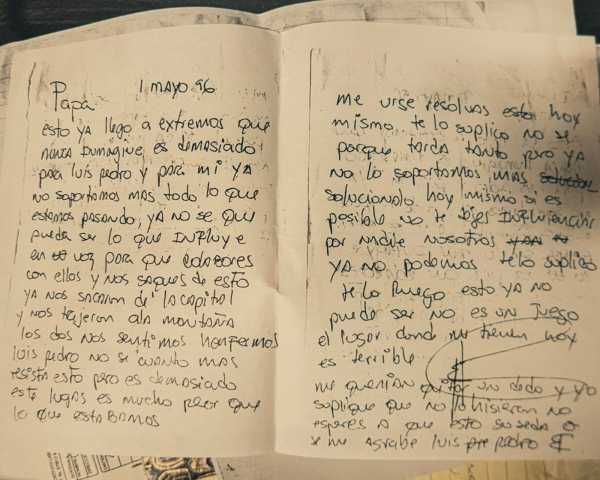

The third proof of life was a letter from Corzo’s father to Corzo’s grandfather.

After police apprehended two of the kidnappers, they made Corzo’s family an offer: they would kill them for a thousand quetzales each.

A bulletproof vest was procured for Corzo to testify at his kidnappers’ trial.

Corzo’s childhood home reflects a certain awareness of this fact. The house peeks out from behind a brown stone wall topped with razor wire. Heavy wooden garage doors are reinforced with steel beams. The sturdiness contrasts sharply with the open-faced squalor of the stash house where he and his father spent the first week and a half of their captivity. In 2019, Corzo returned there—a dilapidated, seemingly abandoned lime-green building on the periphery of Guatemala City. Corzo photographed the exterior from the street.

We move inside by way of archival images. He and his father were kept in a small room next to a garage. A grainy video still shows Juan lying facedown on the floor, wearing only a blindfold and boxer shorts; his hands are tied behind his back, below bleeding gashes that his kidnappers had made with a razor blade. (One of Corzo’s firmest memories, he told me, was of washing his father’s wounds with a damp rag.) The next image is a still of Corzo, at six years old, his eyes also covered by a blindfold. His lips, pursed in a grimace, suggest that he’s been crying. This was one of a series of “proofs of life” that the kidnappers sent to the family. There was also a recording of their voices, which Corzo captures by photographing a CD on which it’s been stored. The notes include a transcript of the recording.

A photograph of a kilometre marker, along the shoulder of a highway, identifies the exact spot where the kidnappers left a third “proof of life.” It’s a handwritten letter dated May 1, 1996, and addressed to “Papa.” The author is Corzo’s father. His wobbly penmanship conjures the terror he clearly felt. “This has reached extremes that I could never have imagined,” he wrote. “We have been taken out of Guatemala City and brought to the mountains.” He added, in reference to his son, “I don’t know how much longer Luis Pedro will be able to resist.” One day before dawn, the kidnappers transported them in separate vans about an hour and a half south of Guatemala City. They were ordered to hike up a steep path, at the end of which were two holes; they spent the next few hours buried to their necks in dirt. Later that day, they were moved to a ramshackle hut of metal and wood. Corzo’s photograph of the mountains might seem idyllic if we knew less about their backstory. It appears to be either dawn or dusk. Clouds float in a soft-colored sky, but there’s not enough light to make out the terrain. The mountains are left in silhouette—imposing, remote, enthralling.

Two of the most important photos in the book, according to Corzo, are among the simplest: images of a folded wad of bills and a tiny bulletproof vest, each set against a cream-colored background. When the police first apprehended two of the kidnappers, an officer called Corzo’s grandfather. “We’ve got two of them,” the officer said, in Corzo’s telling. “If you want, give me a thousand quetzales for each one, and I’ll kill them. You won’t have to go to trial.” Corzo’s grandfather refused. But the family was divided over whether to go to trial. Both views made sense under the circumstances. One was not to get involved any further and risk reprisals; the other was that the family had a moral as well as a practical responsibility to make sure this group of kidnappers wouldn’t go on to commit future crimes. Eventually, the family decided to pursue the legal case. The flak jacket was for Corzo to wear when he testified in court. (Eventually, his parents thought better of having their son participate in the trial.)

A church in the municipality of Pasaco.

While Corzo was working on the book, he learned that Walter Barahona, the brother of one of the gang’s leaders, José Luis Barahona, was being held in a prison known as Little Hell, in a department on Guatemala’s Pacific Coast. On a Sunday morning, in early March, 2019, Corzo drove to the facility. The idea, he told me, was simply to ask Walter if he could share any information about José Luis. For most of his life, Corzo had assumed that the gang leader was dead. But, in the years after their arrests, the kidnappers had filed legal appeals, and their sentences were later commuted. It was only during a visit to Guatemala, while working on the book, that Corzo learned from an aunt that Barahona might still be alive.

Unsurprisingly, given its nickname, Little Hell can be a fearsome place to visit. The inmates wear civilian clothes and aren’t held in actual cells; many of them run their own shops and stalls inside the prison, and can roam freely. Inmates dressed in orange, called zanahorias, or carrots, serve as guides for visitors. Once inside, Corzo asked one of them where he could find Walter Barahona. “He’s not here,” the zanahoria replied. “But his brother is.”

Corzo’s childhood home, in Guatemala City.

He led Corzo to a small food stall. Standing next to a rack of soda and potato chips was José Luis Barahona, the gang leader. “I went numb,” Corzo told me. “He was there, in prison, because of me. Because my family had testified against him.” Corzo recognized Barahona from newspaper photographs, but the former gang leader had to ask Corzo who he was. When Corzo identified himself, Barahona replied without a pause, “Ah! And how’s your dad?” He waited for Corzo’s response before adding, “Look, I didn’t cut his finger off.”

Now that Corzo was speaking with one of the men responsible for his kidnapping, he forced himself to ask the inevitable question: Why had they done it?

Corzo and his father with family members.

“It was like he was reassuring me of what I’d already come to understand,” Corzo told me. “Poverty, necessity, family needs, kids, hunger, lack of work. In Pasaco, there were barely even paved roads. But I asked him, ‘You kidnapped a person. You could have stolen cars, sold them, started a business.’ ” To this, Barahona said, “Why did I have to keep going? At a certain point, it became a mala maña”—a bad habit.

Corzo didn’t record the conversation. He didn’t photograph Barahona, either. Not expecting to find him there, Corzo hadn’t brought his camera, and he wasn’t permitted to bring his phone inside the prison. All he could do was ask Barahona to sign a piece of notebook paper, and to save a bottle of Coke that Barahona had offered him while they spoke. The images of these two mementos conclude the book.

The kidnappers eventually moved Corzo and his father to a small hut in the mountains south of Guatemala City.

When Corzo and I spoke, he described his entire project as an exercise in anti-Bukelismo—a reference to the authoritarian President of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, who has jailed eighty-six thousand people since the spring of 2022, as part of a campaign to rid the country of its criminal gangs. Bukele has become a symbol of populist strength in the region, with admirers in Guatemala and beyond. Corzo saw his own political act as resisting the easy temptation of blind vengeance. He’d been a victim of a ghastly crime, and yet it motivated him to try to understand why it had happened.

There weren’t clear, definitive answers. But when it was time for Corzo to leave Little Hell, he needed an escort to reach the exit. He asked Barahona to walk him out. “The only person I trusted at that moment,” Corzo told me, “was him.”

Sourse: newyorker.com