Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your inbox.

Summer is a season ripe for scandal; people tend to be overheated and understimulated, looking to mist their crisping minds with idle gossip. Minor controversies can boil over, given the right temperature, into full-on imbroglios; such was the case in Paris in 1884, when the twenty-eight-year-old painter John Singer Sargent débuted a new large-scale portrait at the Salon, then the world’s most influential summer art show. Sargent had every reason to feel confident going into the Salon; since he’d arrived in Paris, at eighteen (from Italy, where he was born to American parents), to study at the École de Beaux Arts, Sargent had blazed an ambitious path through the art ranks to become one of the city’s most in-demand portraitists.

“The Birthday Party,” 1885.

Art work by John Singer Sargent / Courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

Sargent’s early work had a more Impressionistic bent—as a student, he travelled through Spain and Morocco painting mystics, courtyards, and beach scenes—but he honed his professional niche in painting portraits of Belle Époque aristocrats, who found Sargent’s sumptuous style (rich, saturated colors, glowy lighting, fastidious attention to little details like fingertips and fabrics) to be immensely flattering. Sargent became famous for making women look beautiful, so it made sense that for years he actively pursued the most famously beautiful woman in Paris to sit for him. Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau—then Paris’s leading It Girl—was, like Sargent, an American arriviste (she was born in New Orleans and moved to Paris at eight); she married rich, and became notorious among the haut monde for her sportive personality and striking looks. (She had a distinctive Roman nose, thick russet hair, a preference for heavy makeup, and a complexion so pale it was nearly translucent.) Sargent expected his portrait of Gautreau (the painting now known as “Madame X”) to be a sensation at the Salon—and it was, but not in the way he hoped. The public hated it. They thought Gautreau looked sickly, bored, and awkward. Sargent painted Gautreau in profile to highlight her regal bone structure; crowds thought it made her look diffident and snotty. He’d painted one dress strap slipping off her shoulder, a move the critics considered profane. (Sargent later edited the strap back into place.) All summer long, the press brayed about the fiasco, to the point where Sargent fled Paris for London.

In 1915, Gautreau died, at only fifty-six, never having quite recovered from her “Madame X” summer. She became so self-conscious about her own image that she had all the mirrors removed from her home. The next year, Sargent sold “Madame X” to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, along with a note calling it “the best thing I have done.” The painting has been a jewel of the Met’s collection ever since—the winds of time have shifted its reputation from disgrace to masterpiece—and it is now the focus of a new Met exhibition called “Sargent & Paris” (through Aug. 3), which explores Sargent’s brief, industrious decade in the city. The show is a perfect summer escape, full of popsicle-saturated colors in cool dark rooms, all leading up to the blockbuster event: “Madame X” comes late in the exhibition, but you can see the painting shining like a beacon from several rooms away. (“The Birthday Party,” from 1885, is pictured above.) And if you need even more refreshing fizziness, you can hit the gift shop to buy a copy of Deborah Davis’s dishy Gautreau biography, “Strapless,” which will allow you to keep chattering about scandále all summer long.—Rachel Syme

This Week With: Jia Tolentino

Our writers on their current obsessions.

This week, I loved texting my friends about “On the Calculation of Volume (Book II),” the second in a seven-book series by Solvej Balle, translated by Barbara J. Haveland. These are the word-of-mouth books of the spring, I think, and it’s been fun to figure out who has been harboring a personal relationship to which specific parts in them.

This week, I cringed at “White Genocide Grok,” the phenomenon where Elon Musk’s built-in X chatbot started replying to many user questions by debunking the idea of “white genocide” and referring to the anti-apartheid song “Kill the Boer.” Actually, I’m kidding, this was the funniest thing I’ve seen on that platform all year.

This week, I’m consuming “Fish Tales,” by Nettie Jones, originally acquired by Toni Morrison before its 1984 publication, and reissued by F.S.G. this year. This book is a party-girl novel like I’d never read before—funny in such a particular register, and so unbelievably full of violence, tenderness, drugs, group sex, exploitation, genuine eroticism, fumbling toward freedom, and some sort of love.

This week, I’m stuck on “Short Story,” the bridge track between “SABLE” and “fABLE,” the two halves of Bon Iver’s new album. Because I listened to the three “SABLE” tracks probably nine thousand times when they were released in 2024, and was trying to transition from my Bone-Deep Melancholy Era into my Searching Complex Bliss Era, I always skipped straight to “Everything Is Peaceful Love,” the happy song I thought started “fABLE.” It is indicative of the fact that I am too stupid to be working at The New Yorker that I somehow did not register, until now, that there is this tiny little bridge track in between—a song that sounds like a rainbow erupting from a handheld prism in a flash of sudden sunlight, a transient perfect epiphany on a walk on a beautiful day.

Next week, I’m looking forward to two shows—Mk.gee at the Stone Pony in Asbury Park, and Perfume Genius at Brooklyn Paramount. I’ve never seen Mk.gee live, despite spending much of last year listening to his album on repeat, and I’ll go see Perfume Genius anytime he’s in New York. It’s impossible to hear 2:00-2:25 of “Left For Tomorrow,” one of my favorite tracks on his new album “Glory,” and not be moved.

About Town

Dance

Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, the founder of Urban Bush Women, recently handed over leadership of that pathbreaking company to younger hands so that she might focus on independent choreography. Now she is starting a term as artist in residence for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, and Ailey’s summer season at the Brooklyn Academy of Music features the first première of that tenure. Made in collaboration with the company members Samantha Figgins and Chalvar Monteiro, “The Holy Blues” looks at the crossover between sacred and secular, the juke joint and the church. It shares a program with two of the hardest works to match: Ronald K. Brown’s transcendent “Grace” and Ailey’s “Revelations.”—Brian Seibert (BAM; June 5-8.)

For more: read Als on how Ailey created a home for Black dancers.

Experimental Pop

A style icon turned dance-music keystone, Grace Jones transitioned from Midtown disco darling to New Wave aficionado in the eighties, settling into an identity as a club visionary. Janelle Monáe emerged in the twenty-tens with her own inspired vision of a humanoid wonderland, on the albums “The ArchAndroid” (2010) and “The Electric Lady” (2013). Her 2023 LP, “The Age of Pleasure,” revelled in the sashaying sensuality of reggae and Afrobeat to create a paradise destination, with Jones as an honored guest. Both artists are masters of the avant-garde, Black futurists, and off-kilter divas. The two join forces for a co-headlining benefit concert supporting BRIC Celebrate Brooklyn!’s free programming.—Sheldon Pearce (Lena Horne Bandshell; June 9.)

Off Broadway

Essence Lotus in “Bowl EP.”

Photograph by Carol Rosegg

For Nazareth Hassan’s zonked-out erotic dream-play “Bowl EP,” the Vineyard has built an entire kidney-shaped pool, a makeshift half-pipe where two lovers-on-the-brink, Kelly K Klarkson (Essence Lotus) and Quentavius da Quitter (Oghenero Gbaje), can skateboard together while getting high and brainstorming songs. Scenes, described album-style, are brief (“Track 4 is tasting fingers,” reads a projection), but small units build: flirtation becomes love; idly proposed lyrics become explosive musical collaboration. The pool is a chain-link paradise, which is to say there’s a devil there (Felicia Curry), with eerie knowledge about what’s to come. The demon’s overlong, high-octane narration of future damage interrupts Hassan’s better flow, though—the EP’s best when it’s a playthrough, laid out track by track, of life in Eden.—Helen Shaw (Vineyard; through June 15.)

Art

The three artists in the show “The Human Situation”—Marcia Marcus, Alice Neel, and Sylvia Sleigh—weren’t friends but colleagues, who painted some of the same models throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties. The show underlines the importance of portraiture to these artists who bucked trends by staying committed to the human form. Indeed, the strongest work by each of these women concentrates with great psychological acuity on what it means to live in a particular body during a particular time. The wonderful Sleigh, who died in 2010, at the age of ninety-four, and Marcus are more narrative based; Neel digs deep into her sitters’ surfaces to get at what they mean to express behind (in one picture) a heavily made-up face that’s steely, off-putting, and completely unforgettable.—Hilton Als (Lévy Gorvy Dayan; through June 21.)

For more: read Als on how Neel captures our collective humanity.

Movies

Jamie Lee Curtis in “Love Letters.”

Photograph courtesy Criterion Collection

Amy Holden Jones’s romantic melodrama “Love Letters,” from 1983, fittingly enters the modern canon with its streaming release on the Criterion Channel. Jamie Lee Curtis stars, in her first major dramatic role, as Anna Winter, a twenty-two-year-old Los Angeles d.j. who discovers a trove of passionate letters written to her late mother by a man who isn’t her father. The discovery inspires Anna to have an affair with a married photographer (James Keach), leading to inner turmoil and open conflict. Curtis dominates the action with her tightly focussed energy, and Jones, who wrote and directed the film in her twenties, unfolds the tale with a distinctive, daringly original blend of local realism, sharp-edged observation, and narrative fragmentation.—Richard Brody (Streaming on Criterion Channel.)

For more: read Jamie Lee Curtis, in conversation with Rachel Syme, on addiction, beauty standards, and encounters with Bette Davis.

Off Broadway

In Jack Cummings III’s revival of William Inge’s 1955 drama “Bus Stop,” a snowed-in Midwestern diner hosts a busload of stranded passengers for a night. The owner of the diner, Grace (Cindy Cheung), is somewhat laissez-faire: she barely notices when an old scoundrel (Rajesh Bose) woos her teen-age waitress (Delphi Borich), and she rather enjoys the cowboy Bo (Michael Hsu Rosen), who has kidnapped a night-club singer, Cherie (Midori Francis), to drag her off to Montana. Cheung and Francis are superb, as is Moses Villarama as Bo’s buddy, Virgil, who sees his own sorrow bearing down on him, inevitable and enveloping, like the blizzard outside. As ever, Inge’s understatement is heartbreaking. When Bo finally repents, Cherie shrugs. “I been treated worse,” she says.—H.S. (Classic Stage Company; through June 8.)

Bar Tab

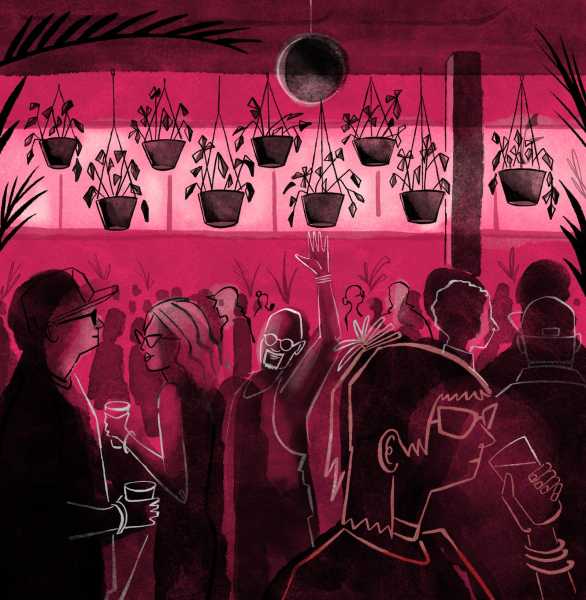

Taran Dugal checks out the dance scene in Ridgewood.

Illustration by Patricia Bolaños

Between 1920 and 1947, the Wolff-Alport Chemical Company extracted rare-earth minerals from a site in Ridgewood, Queens, and dumped the by-product of those efforts—radioactive thorium—into its grounds, thereby contaminating the soil and the surrounding sewer system. The company’s old headquarters sit directly next to Nowadays, a bar and night club that occupies a warehouse and an adjacent, tree-laden lot. There was nothing distinctly nuclear about the venue when a group of friends visited recently, though they soon found themselves in a lurid neon throng on the dance floor. Detroit house boomed from ten-foot-tall speakers framed by an abundance of hanging plants, and patrons swung their bodies to and fro as steam collected on the windows behind the d.j. Phones were notably absent (club policy), and the visitors found themselves keeping time in terms of songs, rather than taps of a screen. After a particularly fast-paced number, they retreated to the bar, where they encountered a white-rum-spiked yerba-mate cocktail, which made for a rejuvenating reprieve. The Zumbador, a Mexican restaurant, served finger foods far more elevated than your typical club fare. Standouts included the birria tacos (shredded goat slow-cooked in chiles, served with a side of consommé) and the tres leches cake, a perfectly sugary chaser. The visitors took their food to the back yard, where, out of the warehouse’s darkness, they emerged into a brightly lit haven. Tired dancers swayed in hammocks; others gathered around contained campfires. As they sauntered toward a picnic table, the guests passed an elderly couple sitting under some string lights. “What do you think?” one asked the other. “Should we get up and dance again?”

P.S. Good stuff on the Internet:

- A Coppola collaboration

- David Attenborough’s most moving marine encounters

- How Matt Wolf makes a documentary

Sourse: newyorker.com