Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Gena Rowlands, who died last Wednesday, at the age of ninety-four, is, of all the actresses I’ve ever seen onscreen, the greatest artist. She’s the one whose performances offer the most surprises, the most shocks, the most moment-to-moment inventiveness, and, above all, the most almost-unbearable force of emotional expression, combining extremes of strength and vulnerability, of overt display and inner life. Her mighty talent is also a peculiar one, the strangeness of which is exemplary of the art of movies: it might never have come so fully to light were it not for her marriage to John Cassavetes and for the movies that they made together—especially the personal six that extend from “Faces” (filmed in 1965, released in 1968) to “Love Streams” (1984).

That’s not at all to diminish Rowlands’s art or its basis in her innate talent and hard work, but to locate its essence in the nature of cinema: it’s an art of collaboration, in which more or less every major artistic advance has resulted from two or more people making common cause. It doesn’t have to be romantic, of course, but it should come as no surprise that this couple, married for thirty-four years, until Cassavetes’s death, in 1989, should be responsible for the most profound movies about love that exist. They met in 1951 at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where they both studied, and married in 1954, when she was twenty-three and he was twenty-four. To do so, Rowlands broke her own vow not to marry in order to focus on her career.

Rowlands quickly got a career, on live TV dramas, on Broadway, and in Hollywood movies. Cassavetes had a similar acting career, although his Broadway experience was mainly behind the scenes, and he also made a pioneering independent film, “Shadows,” between 1957 and 1959 (she had only a bit part, uncredited). They started a family (eventually having three children, all of whom went on to work in film) and moved to Hollywood, where, in the early sixties, Cassavetes directed studio pictures, an experience he hated. They both continued their acting careers, and then, in 1965, they put their own money into “Faces,” much of which was shot in their own house. It took three years to complete, not least because the first cut ran eight hours; Cassavetes ultimately got it down to just over two. The movie, about the fraying of a marriage, is a drama of romantic frustration, longing, and pursuit—the story of a businessman, Richard, who runs away from his wife to spend a night with Jeannie, a sex worker, at her well-appointed home, while his wife has an affair with someone she meets in a night club. Rowlands, in her first real independent-film role—as the sex worker—achieved hitherto-unimaginable heights in movie performance.

A still from “Faces.”

Contrary to myths about Cassavetes’s films, they’re not improvised. The script for “Faces” was two hundred and fifteen pages long, and Cassavetes wrote the dialogue. What’s not written out is the actors’ physical behavior. They’re free to live out the action uninhibitedly, with Cassavetes’s camera following them in their lurches and dances, their tussles and their embraces. The entire cast, featuring veteran actors (such as John Marley, as the husband) and nonprofessionals (including Lynn Carlin, as the wife), performs with unreserved energy and passion, but it’s Rowlands who, in just a few scenes, expands the boundaries of movie acting. The role is one that has the notion of performance built into it—Jeannie is performing love and desire for her client—but the story involves an emotional reality that bursts through this convention-bound relationship.

The sex worker with a heart of gold is a well-worn type, of course, something that the movie confronts head on, yet there’s nothing hackneyed or even familiar about the way that Cassavetes films this character—or about how Rowlands brings her to life. Jeannie’s tragedy is that she is unable to fit into the conventional contours of her transactional role and instead brings her whole self, all her torrential, impulsive emotionalism, to her work. Her intensity provokes Richard into a wrenching-away of façades and engenders a contact of souls far more galvanic than the contact of bodies—until the transactional and the conditional snap back. Rowlands pours herself completely into Jeannie’s ratcheted-up gaiety and forceful control of tough situations, her rapturous tenderness and devastated disappointment. Cassavetes’s filming matches her beat for beat, throb for throb, leading to a closeup of such melodramatic starkness and catastrophic self-awareness that, to my mind, it’s the closeup of closeups, the one that could stand for the entire historical repertory of cinematic intimacy, of the art of the face.

In Cassavetes’s films, Rowlands was able to give of herself comprehensively, to be herself and to allow the wildest extremes of feeling to overwhelm her on camera. This isn’t solely because of the couple’s personal bond. It’s also because Cassavetes, behind the camera, is giving of himself completely, too, in his responsiveness to the people he’s filming and the situations that they create. She and he seem almost to be meeting at the surface of the image, yielding a sense of shared risk, shared vulnerability, and equality.

Rowlands’s performance in “Faces” set the definitive tone for Cassavetes and his films, as well as for herself. In Cassavetes’s 1963 studio movie “A Child Is Waiting,” Rowlands, who co-stars, is skillful and focussed, with a strong presence but an unexceptional manner. In “Faces,” more than a star is born—she reveals an entire new dimension of acting. She wasn’t in his next film, “Husbands,” from 1970 (in which he co-stars with Peter Falk and Ben Gazzara), but his performance confirms her influence. He was already highly original, but “Faces,” in which he doesn’t appear, produced a watershed in his own performances, and in the acting of his movies in general—a form of acting that the entire future of cinema would be forced to reckon with.

By the time Rowlands and Cassavetes made their next movie together, “Minnie and Moskowitz” (1971), they had turned forty, and, in that post-sixties moment, with its slogan of never trusting anyone over thirty, the suburban world of “Faces” was already old-fashioned. Yet, as if to overcome the facile determinism of a generational dividing line, it was this cinematic couple that was singularly rejuvenating the art of movies, dispelling pretenses of comfort and tranquillity to give full and florid expression to the stifled emotions that it concealed. The couple’s films don’t talk politics, but the way that they defied movie conventions to depict experiences with unprecedented intensity gives them a manifest social and metapolitical power.

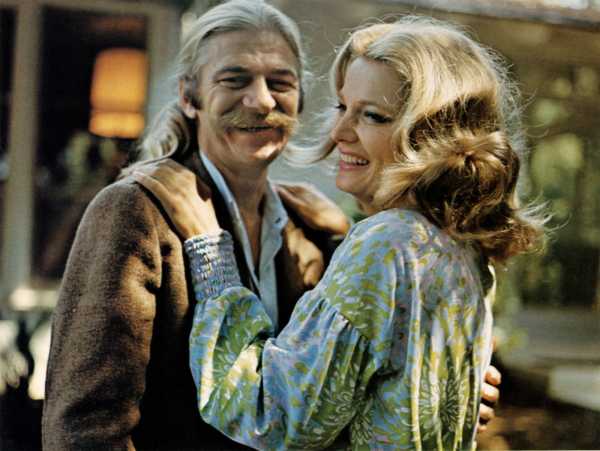

Seymour Cassel and Rowlands in “Minnie and Moskowitz.”

In their 1974 drama “A Woman Under the Influence,” Rowlands, playing the wife of a construction foreman (Peter Falk), confronts the raw and repressive power of working-class masculinity, in a performance that, for all its fury and reckless playfulness, has a finely composed dramatic arc and a manifest virtuosity. Despite this sense of more careful composition, its scenes from a marriage and its vision of family life are nearly unbearably painful to watch; they were agonizing for Rowlands to portray. In 1976, Rowlands was in the room when Cassavetes was interviewed about the film by a journalist from Le Monde, who asked her if she’d thought of directing Cassavetes in a movie. She first jokingly pretended to strangle her husband, then earnestly said that she didn’t want to direct, then added, “No, sometimes, after difficult scenes, I’d like to turn the camera on John, especially to get revenge . . . ”

Having taken naturalistic drama to unprecedented extremes, the couple next explored the very nature of performance, in “Opening Night” (1977), surely the most powerful and imaginative movie about actors—and about an actress—that exists. Rowlands plays Myrtle Gordon, an actress cast in the lead role of a play by an elderly playwright (Joan Blondell), the subject of which is the character’s transition from youth to maturity. The role terrifies Myrtle, emotionally and professionally: she feels that it will mark the end of her career as she knows it, and it also forces her to confront her own age (which is unspecified, but Rowlands was in her mid-forties). It’s also the story of Myrtle’s terror and horror at one particular moment of stage business—when a co-starring actor named Maurice (Cassavetes) is supposed to slap her.

What Myrtle does, in the face of her resistance to the play’s text and to its direction, is to explode the play in real time, forcing Maurice and the rest of the cast to improvise along with her, to the horror of the playwright but to the delight of the audience in the theatre where the play is opening. Those improvisations (most of which were indeed written) range from the dangerously passionate to the uproariously capricious—and Myrtle delivers them as if directly addressing the audiences attending the play and breaking the fourth wall, and forces Maurice to do the same. It’s as if the actors are tipping their hands at movie viewers as well, suggesting the vast personal realities that fuel great screen performances. Most actors and most filmmakers, bound by industry norms or crowd-pleasing conventions, don’t even hint at such realities, but Cassavetes and Rowlands broke open the screen to let them flood into the world at large. The essential art of Rowlands, the art that she and Cassavetes shared in public and in private, was the art of life, the art of love. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com