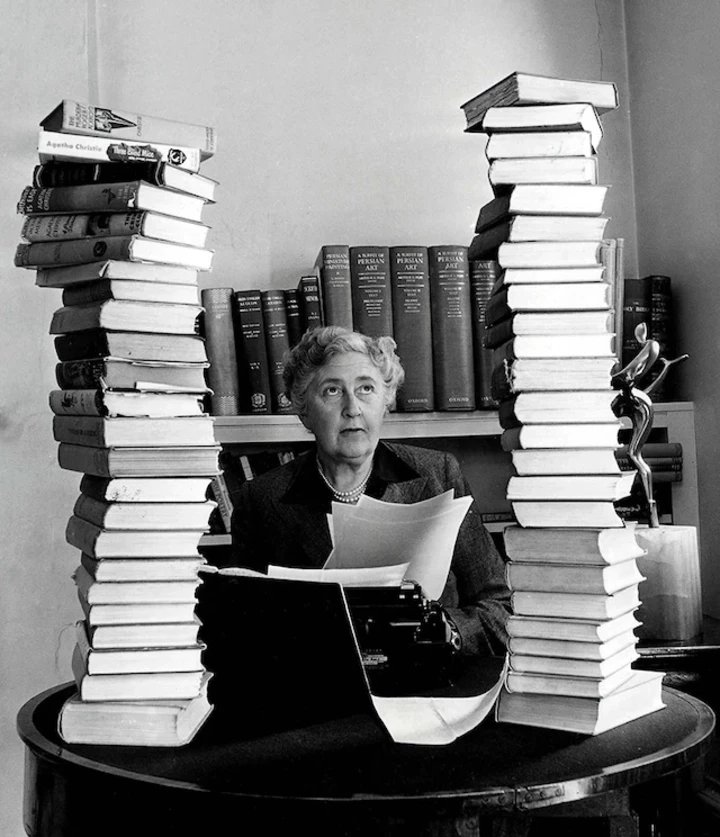

Agatha Christie is the most successful woman in world literature: films based on her novels are constantly being released in theaters and top Netflix hit ratings, and readers have continued to admire her works for several decades.

She is one of the heroines of the book “Pointed Heels” by Vera Ageeva and Rostislav Semkiv, which tells about 14 female authors who changed the course of world literature. We are publishing an excerpt from the book, published by Stretovych Publishing House. It will help you get to know the incredible Agatha Christie, who revolutionized writing.

Advertising.

Agatha Christie (1890–1976) is probably the most successful female author in world literature. She is a unique case, the most widely published writer of all time and peoples – right after the Bible and on a par with Shakespeare. At least the Simon & Schuster publishing house, which founded the tradition of “softcovers” (so-called paperbacks) in the USA, reported that since 1939 almost a billion copies of the author's popular editions have been published (the most widely published novel is “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd”). The total circulation of all the writer's publications is estimated at 2 billion copies.

How did such an unexpected phenomenon arise? It is clear that Agatha Christie took on perhaps the most popular genre of the 20th century, worked extremely fruitfully in it (66 novels, about two dozen collections of short stories), but also made a number of inventions in writing detective stories – they are the most important to us and, apparently, explain the author's exceptional position in world literature.

The writer is being formed in a very special environment. On the one hand, the Victorian era is still ongoing, during which women had no place in universities, and on the other, the world is beginning to change. Agatha's mother is trying to give her and her eldest daughter Margaret a good home education – reading at that time was already seen as a completely natural activity for girls (and a few decades earlier, as we know from Flaubert, it was rather harmful). In contrast, in the British family of the early 20th century, the situation is much more progressive: Agatha Christie recalled how one rainy day, when she was eight or ten years old, her mother came into her room and said: “If you're bored, sew a pillow or write a story.”

The total circulation of all the writer's publications is estimated at 2 billion copies.

Interestingly, this is seen as an equal choice: if she wanted to, Agatha could sit down and start writing. Meanwhile, her sister Madge was already writing. Magazines even accepted her rather traditional, elegant stories for publication. However, her sister ended her literary career as soon as she got married and focused on the duties of a married woman. Agatha, on the other hand, tried her hand at writing in different ways: she appeared in literature with poetry, and proved herself as a successful playwright (by the way, her play “The Mousetrap” is one of the few that has not left the English stage since the 1950s).

In the end, Agatha shared with her sister that she would like to write detective stories, to which she objected, saying that Agatha would definitely never write such a thing. The sisters even had a bet on a bottle of champagne. This bet finally convinced the writer to try. As we can see, everything is logical: there was a certain reading and writing culture around the future author, but then the time came for an experiment, which ended in such unprecedented success.

So, Agatha Christie seems to still belong to the Victorian era, but at the same time she sees far into the 20th century. The insight of her works lies in the implementation of a truly feminist revolution in the detective genre: it was Agatha Christie who first created the popular image of a female detective. From under her pen, Miss Marple eventually appears, a traditional British lady, for whom housekeeping, gardening and knitting do not prevent her from creating an intellectual context around those mysteries that even the most famous male detectives fail to solve. Miss Marple is inconspicuous and quiet, but attentive enough to notice the smallest details (or rather, “to stick her nose in other people's business”), and her mind is sharp enough to draw the right conclusions and expose the perpetrators, of whom, by the author's will, there are an abnormally large number in her neighborhood. She has lived her entire life in the small village of St. Mary Mead, which Agatha Christie invented, but is most often associated with one of the small towns southwest of London – in the counties of Hampshire or Devon.

The former is in favor of the fact that it is quite easy to get to the capital by train from here (which is often done by the characters in her books). But these are generally interesting places: in Chawton there is Jane Austen's house, not far to the north we have Stonehenge, and even further – Oxford, where J. R. R. Tolkien lived, and in the vicinity of the county capital Southampton an amusement park with a Peppa Pig house has recently appeared. It was in Hampshire that the BBC filmed films based on Agatha Christie's books; Miss Marple, played by Joan Gickson (selected personally by Agatha Christie), lives in one of the houses in the village of Nether Wallop on Five Bell Street in the series. However, some of the places where Miss Marple investigates murders are in Devon – the home county of Agatha Christie, who was born in coastal Torquay. Her house has not survived, but in its place there is a traditional “blue plaque” that is installed on all famous houses in Britain. There is also a monument to Agatha Christie in the city – she sits on a bench in the port with a dog at her feet – just like the actor Mykola Yakovchenko near the Franko Theater in Kyiv. Only Yakovchenko has a dachshund Fan-Fan, and Agatha has a fox terrier Peter, who inspired the writer to write the novel “Silent Witness”.

But let's return to the feminist revolution in the detective genre: on the one hand, Agatha Christie develops the tradition of famous British (Arthur Conan Doyle, Richard Austin Freeman, G.K. Chesterton, Edgar Wallace) and French (Emile Gaborio, Maurice Leblanc, Gaston Leroux) detective authors, so to speak, the tradition of the most famous investigator – Sherlock Holmes; on the other – she breaks with it, bringing to the fore the wrong detective. (By the way, Sherlock investigates his most famous case in Devon, or Devonshire: it is there that the fictional Baskerville estate and the real endless swamps that inspire melancholy longing are located.)

For several decades, Agatha Christie has been fighting for a woman's right not just to be an intellectual, but to be an effective intellectual, on whom much depends.

First, Agatha Christie brings to the forefront the funny mustachioed Poirot, who is completely different from the snobbish dandy Holmes, or the staunch Father Brown, or the hyperactive investigators of French authors. The Belgian Poirot is emphatically a stranger in Britain, which immediately raises the question of the inclusiveness of the genre and destroys the idea of its unequivocal patriarchal nature, because Hercule has quite a few habits that are suspicious from the point of view of dominant masculinity: he is fond of cooking, grows roses and is incredibly meticulous in caring for his mustache. In fact, all that remains of tradition is his sharp mind and a somewhat paternalistic attitude towards women. Then the writer introduces a pair of detectives into the genre – a man and a woman. Tommy and Tuppence appear in only five stories, which is directly related to Agatha's divorce in 1926, when her faith in the common cause collapses. And almost immediately after this tragedy – in 1927, in the collection “Thirteen Cases” – we already see Miss Marple. The first novel with her participation is called “Murder in the Vicarage”; it was published in 1930. Agatha Christie herself writes in “Autobiography” that Miss Marple is the reincarnation of her grandmother Margaret Miller, but, it seems, this image also contains self-projection: Agatha, imagining herself old and divorced, assumes the image of a respectable, somewhat strange intellectual “from the locals”, who decisively changes the balance of power in the genre – since then, female investigators have become familiar characters in detective stories.

…

Thus, for several decades, Agatha Christie has been winning back the right of a woman not just to be an intellectual, but to be an effective intellectual, on whom much depends. And this in such an important and indicative genre for British literature as the detective story.

Agatha Christie's detectives are always a little more than just complicated stories or mysteries to be solved. The writer is very good at depicting what authors of the detective genre usually do not pay attention to at all. From Christie's novels, you can study Victorian life, architecture, customs, dances, cuisine. And Miss Marple's success is also connected, in particular, with her excellent knowledge of the local context: who should go where and when. A kind of genius of the place, inaccessible to a stranger, to anyone who interferes from the outside. Miss Marple knows exactly when order is broken: if the milkman or the baker arrived at the wrong time or in the wrong place, this provides an absolute key to the solution. For example, in “Murder at the Vicarage”, Miss Marple says that she saw the suspect walking to the house at such and such an hour, and emphasizes that she knows the cut of her dress well: she could not have brought a revolver with her. And in “Murder Declared,” interior elements, old photos, and the cat's behavior become the key to reasoning.

A detective is impossible without attention to detail, but Agatha Christie's characters demonstrate a special type of attention – less formal, much more variable and flexible. Sherlock Holmes pays less attention to milliners, hairdressers or how the style of clothing can affect the style of the crime. Playing with the formal prescriptions of the genre and abandoning the usual straightforwardness also explain the writer's success. Of course, Agatha Christie's texts set a new and very high bar with their precision, intellectual contexts and complex sophisticated games, and also had an extremely strong influence on the development of the genre as a whole, in particular on the formation of the Scandinavian detective school, among whose authors, by the way, there are also women. In Britain at the time of Agatha Christie, she was imitated and experimented with by quite popular female detective authors: Dorothy Lee Sayers, Nyein Marsh, Josephine Tay and Margery Allingham. The tradition was then picked up by Phyllis Dorothy James, Ruth Randall, and, of course, J.K. Rowling (under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith) — but isn't there a lack of detective stories in the Harry Potter saga itself? Agatha Christie, meanwhile, still remains unique and unsurpassed — the true queen of the detective story.